When Juan’s finger got caught in a carrot-peeling machine last year – almost dropping his digit into his carrots – his cry immediately caught co-workers’ attention.

“Ahh! My finger! My finger!” he screamed. Juan’s boss approached, concerned.

“How is the machine?” the boss asked, “Is it still working?”

Juan, a temporary Mexican worker in Cloverdale, B.C., wasn’t sent to a hospital. He was given a Band-Aid and a glove and ordered to return to work. But he refused, demanding his right to treatment. He phoned the Agriculture Workers Alliance (AWA), a union-linked organization offering support to foreign farm workers. AWA’s Raúl Gatica rushed him to the doctor.

“[The doctor] sewed the finger on, and after that she asked where the worker was working,” Gatica recalls.

“After that, the doctor never sent a report to WorkSafeBC [the province’s worker compensation program]. She didn’t even want to give him a day off work. I asked why? I had to push and push and push until she gave him a doctors’ note for some days off work – only after I pushed her.”

Doctors are legally obligated to report to WorkSafe if a patient informs them of injuries incurred while working. In this case, however, Gatica says they had to use repeated pressure from AWA to get the doctor to file a report.

Gatica alleges a pattern of collusion between bosses and cherry-picked, employer-sympathetic physicians, one of many barriers faced by Canada’s 150,000 migrant workers.

Just like Juan, migrant workers and refugees are demanding dignity, often at great risk, both individually and collectively. Despite government assurances of workplace inspections, violation penalties, and coverage for all, ask anyone treating migrants and the horror stories pile up. Those who speak out say they are placed on visa blacklists by their own governments.

The repercussions are often deadly. In June, Mexican blueberry farm worker Luis Perez Dzul developed brain cancer, believed to be linked to pesticides. After surgery in B.C. he was ordered home – only to die two weeks later in Mexico. Other foreign workers’ nightmares include a series of mushroom fume fatalities in Vancouver, and a van crash in Stratford, ON, that killed 11 farm workers, most of whom were from Peru.

Other injuries, if not deadly, are life-altering. A Mexican jockey crashes, breaking his legs and killing his horse; he’s ordered to pay tens of thousands of dollars for surgery, loses his job, and must leave Canada. A fruit-picker with a work-related knee injury is charged $700 for hospital care; when he can’t pay, police are called. Workers, forced to pass medical exams before arrival, are returned home broken and unable to afford care.

“This is almost a situation like feudal times,” says AWA’s Gil Aguilar, explaining that workers face pressure to work despite injuries or illness. “[Bosses] want their employees – their serfs – to be as ignorant and quiet as possible.

“Health is one of the most obvious windows into all the conditions they have to face, because it’s so basic. Some workers…have hernias. They’ll bear those hernias for the full season until they go home. Sometimes they have broken toes or fingers, or cavities that are really painful. They just take it, because they don’t want to jeopardize their work. They are told all the time that they’ve come here to work: not to complain, not to ask questions. If they don’t like it, there are 10 other workers waiting to take their job.”

In an era of cutbacks – particularly under austerity reforms like reducing migrant wages to 15 per cent below median regional incomes – a long-simmering migrant health crisis is exploding.

A spokesperson for Human Resources and Skills Development Canada (HRSDC) told Briarpatch that new wages obey existing minimums and simply drop migrants’ earnings to match those of Canadians. They insist foreign workers have health coverage: private for three months, followed by medicare.

“Temporary foreign workers have the same rights and protections as Canadian workers under applicable federal and provincial employment standards and labour laws, and they are paid at the same wage as a Canadian worker for the same job in the same location,” said HRSDC spokesperson Amélie Maisonneuve.

But policies, apparently, contradict experience. Many foreign workers say they face numerous barriers to health care, workers’ compensation, or other benefits they paid into. In some provinces, they’re even banned from unionizing. And the problems are not just for workers. Undocumented pregnant women, caught up in increasingly draconian immigration laws, are often reluctant to seek help for fear of detention or deportation.

Vancouver activists convinced one hospital to treat such women, case-by-case, to avoid deadly complications. Midwives have also stepped forward to help. As the crackdown on so-called “bogus” claimants and “irregular” arrivals escalates, the number of undocumented patients grows.

Another crisis arrived on Canada Day, when the Interim Federal Health Program caused thousands of refugees to lose access to specialists, medications, mobility aids, and more. The move was ostensibly intended to prevent asylum-seekers from getting coverage unavailable to some Canadians, such as minimal dental- and eye-care. But advocates said that the lost benefits had been important in preventing emergencies, since refugees can’t access employer insurance or low-income subsidies. The cuts saw unprecedented health worker protests, including a 90-physician sit-in.

Dr. Bob Martin of the Bridge Refugee Clinic, a newcomer care facility founded by refugees and immigrants, does not mince words.

“As a consequence of these health-care cuts, many relatively simple health problems will become overwhelming and life-threatening,” he says at a Vancouver rally. “Tragic outcomes from these policy changes are not just a possibility – they are a certainty.

“There will be children with epilepsy who won’t receive anti-seizure medication. There will be adults with heart failure who won’t receive diuretics. And there will be children who need insulin whose parents cannot provide it. With luck, these individuals may get to hospital in time to avoid tragedy. But obviously not all will make it. Clearly, our government has undertaken a program of scapegoating our weakest and most voiceless among us.”

For Iranian refugee Tara Pedra, a translator at Bridge Refugee Clinic, the health cuts are inexplicable. “A refugee life…is very, very difficult and hard,” she says. “Many who were healthy in the beginning, in the transition countries, become sick; they become ill, they become depressed.

“Now when they come to Canada, through the whole trauma, it really makes me sad there will be no medication or medical assistance for them. How can we have a healthy society when we treat them like this?”

For Aguilar, the health issues of temporary workers, undocumented migrants, and refugees are linked.

“The most obvious connection is that [they are all] building this country,” he explains. “Refugees and migrants both come here and build our economy to support their living.

“We are benefiting from the horrible conditions of temporary workers and refugees, whether they are in the fields, in hotels, restaurants, or in our houses taking care of our children and our elderly, they often work the same jobs. The connection is very clear to me. They lack access to the same rights and benefits that we think we have.”

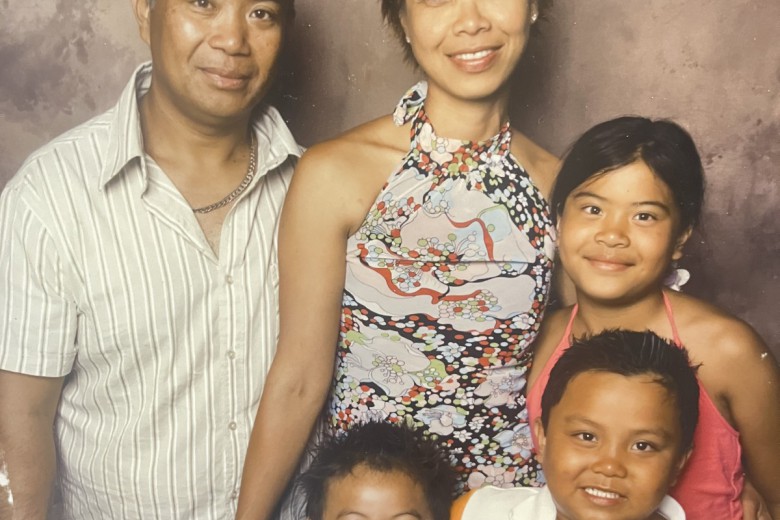

Joy, a Filipina domestic worker, told Briarpatch she felt like a prisoner in bosses’ homes, where she is prevented from seeing a doctor, making phone calls, or communicating with her family.

The medical implications of isolation are clear, and abuse and homesickness foster depression. But domestic workers are resisting by creating support groups and educating people about their rights.

Across the board, self-organization, community mobilization, and migrant leadership are key themes – from migrant-founded mobile clinics to safety workshops and political advocacy.

Byron Cruz, a refugee from Guatemala’s civil war, agrees. After arriving, he volunteered in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside among many Latin Americans involved in the earliest campaigns for needle exchanges, safe injection sites, and harm reduction. He began sharing his community organizing experience from Guatemala.

“We came from experiences where we were losing our friends in the civil war in Guatemala…and we came with a great experience in organizing communities in our country of origin,” Cruz explains. “At least here, we had a chance to look for solutions. We saw that, as immigrants, we could use our expertise in organizing communities to start something.

“But I don’t believe self-organizing is just about creating health services. It is also a way to pressure governments, to let them know they’re responsible for providing and facilitating health care.”

Self-organizing also means coalition-building. In response to health barriers for refugees, foreign workers, and undocumented people, a new coalition has emerged: Sanctuary Health. The group joins activists, doctors, social workers, and farm worker advocates in demanding that health-care providers accommodate open access to services.

“We want to see a policy of zero barriers for refugee claimants,” Cruz says. “We would like to also see Medical Services Plan [B.C. health care] implemented for migrants in general.”

The crisis is not only for newcomers.

“This should be a wake-up call for Canadians, because these migrants are facing the same health-care system that we are, as Canadians, but on the fringe,” Aguilar concludes. “This health-care system we have in Canada, even though it’s better than others, is being gradually gutted. It’s treating all of us worse.

“This is not an isolated area of migrant workers versus health care. It’s all connected: through health, we can see the most basic aspects of how things are not working.”

*Some names have been changed to avoid repercussions from employers.