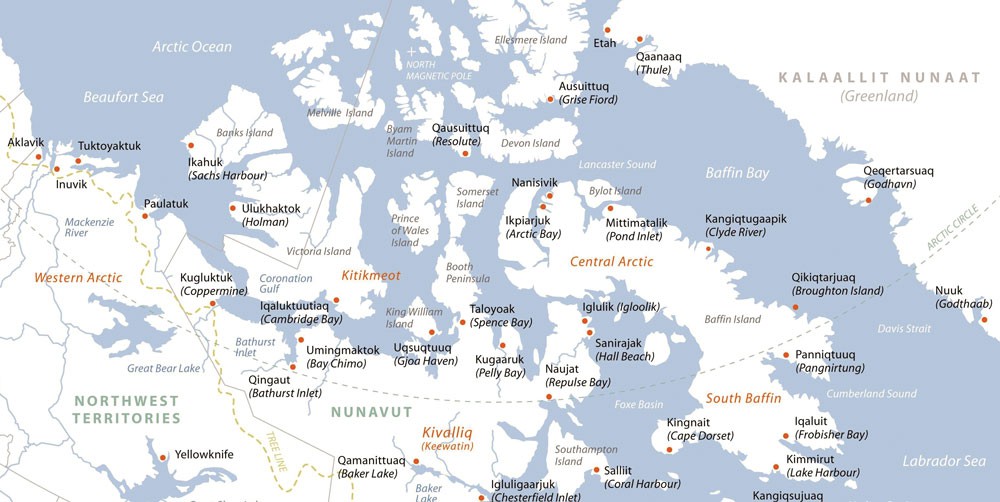

Jerry Natanine is an Inuk hunter and father and the current mayor of Clyde River, a hamlet of less than 1,000 residents on the northeast shore of Baffin Island, in the Baffin mountain range. The area is host to many coastal fiords where Indigenous hunters have always harvested a variety of sea mammals. When the Clyde River community learned about new plans to conduct seismic surveys in search of hydrocarbon deposits off the coast, Natanine says, “Our first concern [was] the effect on the animals, marine mammals, because that’s our way of life.”

Since 2011, when a consortium led by Multi-Klient Invest AS (MKI) first put forward the proposal to conduct seismic surveying off the coast, residents of Clyde River have been waging a political battle against the oil and gas industry. The proposal has faced consistent and committed resistance, with petitions opposing the seismic work submitted to the National Energy Board (NEB) by residents of Clyde River in 2011 and Pond Inlet in 2013. The hamlet council and the Hunters and Trappers Association of Clyde River passed joint motions opposing the surveys in 2013 and 2014. In March of 2014, a meeting of all mayors from the Baffin Island region unanimously passed a motion in opposition to the proposed surveys.

Despite this widespread opposition, the proposal by MKI was recently approved by the NEB. The northeastern Canada 2D marine seismic survey would involve ships using air guns to blast bursts of sound into the water to study the geology below the ocean floor. The survey would take place seasonally, over five years, and cover areas in Baffin Bay and Davis Strait. The information collected would then be sold by MKI to oil and gas companies and used to help locate hydrocarbon deposits.

“We heard about seismic testing being done in the western Arctic and people experiencing what they did, and in the early ’80s they did a little seismic testing right near Clyde,” says Mayor Natanine over the phone. “And people saw what that did to the seals. And this time around, people know a little bit about it, and they didn’t want anything to do with it.”

Concerns with the impact of seismic surveys on marine mammals, including seals, whales, and walruses, have been expressed by Indigenous peoples and conservationists worldwide. These animals form the basis of Inuit hunting culture on Baffin Island.

Natanine explains that the community also does not necessarily need the potential employment and contracting opportunities oil and gas development may bring to the region. The massive Mary River iron ore mine, operated by Baffinland, is currently under construction northwest of Clyde River. Once operating at full capacity, the Mary River mine would be the largest industrial project in Canada’s North. Baffinland’s project will likely exhaust the community’s industrial labour force and local business capacity into the foreseeable future.

“In our community meetings … there was a consensus – and that’s my view, too – that Mary River is enough for the time being for all of north Baffin,” says Natanine.

When it comes to oil and gas development, he says, “not this time, not right now.”

The Inuit of Baffin Island have been subjected to numerous colonial injustices. In the mid-20th century, Inuit experienced residential schooling, the slaughter of sled dogs by the RCMP, the imposition of colonial hunting regulations, and population relocations by the federal government. Later, in the early 1980s, anti-fur activists undermined the Inuit hunting economy by lobbying the United States and European Economic Community to ban the import of sealskins from Canada. To this day, Inuit struggle against the animal rights lobby to keep markets open for products of Inuit harvesting – most notably seal and polar bear pelts, as well as walrus and narwhal ivory.

For Natanine, MKI’s proposed seismic survey and the NEB’s review process are the latest in the long line of injustices the Inuit of Baffin Island have suffered.

“We’ve experienced injustices through the settlers settling and dog slaughter and stuff like that. What these companies want to do with seismic testing and oil extraction, I saw this as an injustice to people, and people not having a voice to fight it. That’s why I took it up.”

Against ExtractionThe movement to stop the MKI proposal is the latest in a series of battles Inuit in Nunavut have fought against offshore oil and gas extraction.

1971: Inuit in Coral Harbour successfully lobby the federal government to place a moratorium on offshore oil development near their community.

1978: The government of Canada places a temporary moratorium on oil development in Lancaster Sound in response to Inuit opposition to a proposal to drill an exploratory well.

2010: Inuit on Baffin Island successfully oppose a proposal to conduct seismic surveys in an area that includes Lancaster Sound.

The Qikiqtani Inuit Association (QIA) – the representative Inuit organization for the Inuit of Baffin Island – responded to the massive public opposition to seismic surveys by calling on the federal government to conduct a strategic environmental assessment into the broader question of opening the region to offshore oil and gas development. QIA has insisted that MKI’s seismic survey not be approved until the broader strategic environmental assessment is complete. In February, the ministry of Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada (AANDC) initiated the strategic environmental assessment.

Natanine says he was pleased that a broader environmental assessment is being carried out, but he has some reservations. He wants information on the impacts of seismic surveys to be provided in an accessible format so Inuit in Clyde River came make their minds up for themselves about the issue.

“I like the fact that there’s a process like that, but one main concern is that people want to see [film of the sound blasts] and let us watch that there’s no effects,” Natanine says. “We’re visual people and we react to what we see. If it’s going to be the same just empty words, that’s what people don’t want to see.”

Natanine is also concerned that there is no public registry or other public record being kept of the assessment process. “I think there should be a public record of it available to anyone. But the way they’re doing it, they’re really secretive.”

In April, QIA and Nunavut Tunngavik Incorporated (NTI) – the representative Inuit organization for all Inuit in Nunavut – wrote a joint letter addressed to the NEB chairman and the minister of AANDC. The letter reiterated the position that the seismic survey should not be approved until the strategic environmental assessment is complete.

On May 26, the NEB responded to the joint letter from QIA and NTI, saying it would release its decision and report once other federal government agencies had approved benefit plans for MKI’s seismic survey. The letter made no direct reference to QIA and NTI’s appeal to have the process halted until the first stage of a strategic environmental assessment is complete.

On June 10, AANDC Minister Bernard Valcourt responded to QIA and NTI’s letter, stating that he sees “neither the need nor the benefit to put seismic exploration on hold while strategic environmental assessment work is underway.”

On June 26, the NEB announced its approval of MKI’s seismic survey. In a press release, the board boasted that “never before has there been this level of public participation in the Board’s Environmental Assessment process.” The press release neglected to mention that the vast majority of public input was opposed to the proposed surveys. The consortium led by MKI responded with a July 16 letter to the NEB stating they plan to begin work next year.

The Hamlet of Clyde River responded to the NEB decision by starting a petition to send to the House of Commons, calling on the federal government to reverse the decision. At the time of writing, the hamlet was seeking a member of Parliament to table the petition and weighing options for litigation.

Regardless of what course of action Clyde River ultimately decides upon, Natanine stresses that it is important for Canadians everywhere to follow Arctic politics and support Inuit when they take a stand against extractive projects to which they do not consent.

“There are few of us Inuit in this country, under 30,000 Inuit in the territory. We need all the support we can get from other Canadians in the South, especially when Inuit take action,” says Natanine. “When our community first took a stance against seismic testing off our coast, no environmental group engaged with us at all; that’s the way they’ve always been. That has to stop, and we have to work together to fight the destroyers. When Inuit stand up to fight the oil industry, we need people in the South standing up with us to let the world know of what is happening here.”

Follow Clyde River’s struggle at Nunatsiaq