Organizing a camp takes all hands on deck. My recent visit to Oceti Sakowin Camp on Standing Rock reservation was no exception. While police surveillance of the camp goes round the clock, so does the tireless labour and work required to winterize the space with the impending cold.

The evening of November 20 marked perhaps the most violent attack of Standing Rock water protectors by militarized police to date: the Standing Rock Medic and Healer Council estimated that 300 people were treated for injuries and 26 people were taken to hospital. Protectors at Standing Rock are resisting the construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline, which is to cross the Missouri River just north of the Standing Rock Sioux reservation. It had previously been planned to cross the river north of Bismarck, ND, but it was rerouted to its current path after the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers determined it would threaten municipal water wells.

Protectors defending the Missouri River from the pipeline are not unacquainted with weapons euphemized as “less-than-lethal”: rubber bullets, concussion grenades, and teargas. The most disturbing use of force against the brave souls who are protecting water in Sunday night’s attack was the militarized police’s abuse of water cannons in freezing temperatures. Unicorn Riot reported that a 13-year-old girl was shot in the face by law enforcement; two people suffered the effects of cardiac arrest. Many suffered from hypothermia. With winter quickly approaching, winterization and warmth in the camp is needed now more than ever.

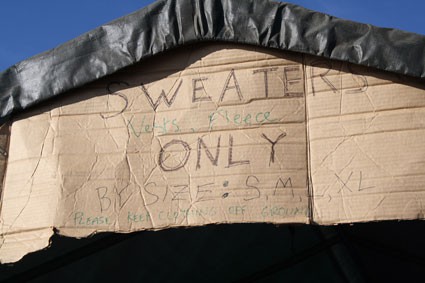

The developed camp houses seven kitchens, a main meeting dome and a mess hall, a medic centre, art spaces, donations tents, two sacred fires, a carpentry shop, a school, and plenty of individualized sleeping quarters. All of these spaces require revamping for the coming cold. Often, that entails insulation and flooring, and indoor propane heating.

The prairie cold in North Dakota is harsh and biting, and many allies and visitors from more temperate climates can be unaccustomed to it. The winterization process is all the more urgent to ensure that all protectors – those from the prairies or elsewhere – are insulated from the elements.

Liam Cain, a trade unionist with LIUNA 1271/IWW EUC, understands that winterizing is part of the long haul resistance. “The folks staying for the winter are inspirational and determined, and coming from Wyoming I recognize the necessity of solid, weatherproof shelter to get through the bitter cold.”

Cain, who has a general background in construction and is also a representative of Labor for Standing Rock, knows firsthand of the efforts required for the winterization process. “We were buying things in bulk – 2×4s, plywood, fasteners, screws,” he explains. Cain went on countless supply runs to assist the process. “Our motive was just to plug in with the people already starting the work and help bridge the gaps.”

In my short time at the camp, I volunteered in a kitchen operated by an Indigenous woman named Rachel. The kitchen recently had insulated flooring installed with the help of Cain and others associated with Labor for Standing Rock, and moving and organizing her space was the next step in promoting a smooth functioning kitchen to put warm food in the bellies of the water protectors.

If you’d like to assist with the necessary supplies for the progression of the camp, please donate to: http://www.paypal.me/ocetisakowincamp

Follow regular updates at the official website for Oceti Sakowin Camp.