People have always roamed – to the next settlement or across oceans. But migration as we know it today – controlled by borders, visas, and passports – has a more recent origin, emerging from the birth of the nation-state.

Ever since we carved up the world into chunks, sovereignty has been the principle upon which we have built modern nations. One of the most fundamental tenets of sovereignty is the right to regulate entry.

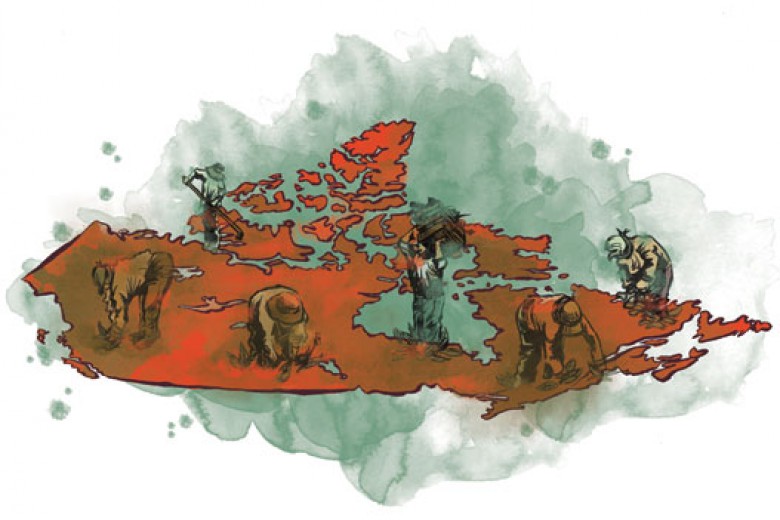

Today, there are 70.8 million people who have been forcibly displaced worldwide. But behind closed doors, the countries that people risk life and limb to reach are doing everything in their power to keep them out.

The origins of asylum

In 1938, representatives of 32 countries convened in France to find a solution to the increasing number of people fleeing Nazi Germany. As a solution, they created the Intergovernmental Committee on Refugees, an organization that aimed to extend protection to would-be refugees inside the country of potential departure. But it was little more than lip service, as it had negligible authority, received almost no funding, and no country except the Dominican Republic even offered to take in refugees. Not a year later, a ship carrying 937 Jewish refugees was turned away by Cuba, the U.S., and Canada before returning to Europe, where 254 of its passengers were murdered.

This could have been an incredible step – a codification of refuge, an acceptance of asylum’s inviolability – except that it wasn’t.

It was more than a decade later that countries eventually gathered to draft the 1951 Refugee Convention and later the 1967 Protocol, setting forth an international agreement on how to deal with refugees that has since guided the UN’s work.

This could have been an incredible step – a codification of refuge, an acceptance of asylum’s inviolability – except that it wasn’t. It was all bark, no bite. The convention does not compel countries to grant qualifying individuals asylum; it only says they should. This single word has left us with a politicized, piecemeal system that too often leaves people fleeing persecution stuck between a rock and a hard place.

Walls: the bigger, the better

For far too long, the Global North has performed ruthless political acrobatics in the name of protecting borders. There are the obvious ways, like building bigger walls and creating harsher laws. The ones we see, read about, and (occasionally) disavow.

Hungary has built a 100-mile-long razor-wire border fence armed with heat sensors, cameras, electric shocks, and loudspeakers to “stop the flood” of migrants. Two Spanish enclaves, Melilla and Ceuta – politically part of Europe, but geographically in Africa – also have a border “fence” comprised of three towering walls and equipped with infrared cameras, barbed wire, motion sensors, and watchtowers. Any attempt to cross the barrier can be fatal. During one attempt in 2005, more than 10 people were shot dead, many severely injured, and hundreds deported or abandoned in remote locations in just a few days.

France wants to “take back control” of its migration policy, introducing a 20-point plan that would implement more checks to “fight against fraud and abuse,” and bar all asylum seekers from access to health insurance during their first three months in France. India has approved a bill that accepts undocumented religious minorities from neighbouring countries, but deliberately excludes Muslims.

The U.S. Department of Defense has deployed 5,500 troops to the U.S.-Mexico border and has diverted US$3.6 billion to construct a border wall. It has proposed changes that would prolong the waiting time for some asylum seekers to apply for work authorizations and completely prohibit others from doing so. Another proposed rule would bar people who have been convicted of certain crimes, like driving under the influence, from seeking asylum.

If an individual is lucky enough to make it past the red tape and walls, countries have another trick up their sleeve: make the living conditions so abhorrent that migrants feel as though they have no choice but to leave.

At the U.S.-Mexico border, thousands are forced to wait in Mexico to have their refugee claims heard in the U.S., but the conditions are so dangerous and the situation so unclear that in one week, half of the registered asylum seekers gave up on their claims and left the camps.

If an individual is lucky enough to make it past the red tape and walls, countries have another trick up their sleeve: make the living conditions so abhorrent that migrants feel as though they have no choice but to leave.

In Bosnia – where migrants play what they call “the game,” trying to evade Croatian police and make it into the EU – thousands are left sleeping in fields and abandoned buildings. Those who manage to stay in the camps aren’t better off. Vučjak camp, for example, is built on an old landfill, so filthy it is “inadequate for accommodating human beings,” and at risk of a methane explosion due to reactive properties in the soil below the camp.

In Greece, life is no better for migrants. Camps are dangerously overcrowded – there are more than 7,500 migrants in the Vathy camp, which has a capacity of just 648, and migrants at Moria camp face “hellish conditions,” where over 12,000 people are forced to coexist in a space intended for 3,000.

Bosnia and Greece have their own problems – Bosnia has the world’s most complicated government system that leads to slow and complex decision-making processes, and Greece has long been on the brink of economic disaster – so perhaps it isn’t surprising that migrants aren’t hosted in better conditions. That said, these situations highlight the lack of EU engagement. While the EU border agency doles out millions to Croatia for border personnel and surveillance equipment, the EU continues to ignore the inhumane living conditions for migrants on its soil.

Behind closed doors

The erosion of our migration system doesn’t just look like far-right xenophobes proudly spewing slurs. In fact, most of it isn’t. Behind walls and barbed wire, global powers use more covert ways to keep their nations free from unwanted – mostly poor and Black and brown – newcomers. Through handshakes behind closed doors, with refugees as commodities and borders as bargaining chips, our migration system crumbles.

Inter-state negotiations over migration flows and border controls, known as migration diplomacy, have long been the oil that greases the global migration machine. Through the practice of “externalization,” wealthy countries outsource migration control to poorer countries, enticing them with money or threatening them with tariffs. In exchange, poorer countries play gatekeeper, employing dangerous and coercive methods to stop migrants from reaching the borders of the wealthier nation.

Externalization is about keeping migrants from reaching a nation’s doors – because once they knock, they’re your problem. In international law, when a person sets foot on a country’s territory (including territorial waters), they become that country’s responsibility and it must then adhere to its legal obligations. A country must offer every individual the opportunity to launch a refugee claim, and it cannot send asylum seekers back to a place where they would face persecution.

Through the practice of “externalization,” wealthy countries outsource migration control to poorer countries, enticing them with money or threatening them with tariffs.

Europe does everything it can to keep migrants from knocking on its door. The continent has been at the forefront of migration diplomacy, striking deals with dozens of countries. Its most significant tool is the European Union Emergency Trust Fund for Africa (EUTF) – a multibillion-dollar fund to prevent migration to Europe by increasing border controls and by funding projects (anything from “migration management” to employment opportunities) in 26 African countries.

Under the EUTF, countries receiving funding “are considered to be in a crisis situation” for as long as the fund exists. Because of this self-proclaimed crisis, the fund’s €4.6 billion can be allocated without an open call for proposals and to any of the countries. The EU funnels money to these countries, without checks and balances, essentially paying them off for ensuring that migrants stay on the African continent.

In Europe’s game of migration diplomacy, Libya has been a key player – or pawn. As Africa’s biggest gateway to Europe, wealthier nations have long funnelled money into Libya to keep migrants away from Europe’s doors. Despite evidence that Libya is rife with militia groups and human traffickers who kidnap, extort, and torture migrants, multiple EU-backed pacts that aim to halt “illegal migration” have made Libya the de facto border patrol for Europe.

With the EU’s blessing and chequebook, Italy has maintained a deal with Libya since 2017 with the aim of keeping migrants away from Sicily’s shores. Italy trains, equips, and finances the Libyan coast guard in exchange for Libya intercepting migrants at high seas and pulling them back to Libya, where migrants live in inhumane conditions and consistently face torture and abuse. Amnesty International has condemned both Italy and the EU for being “complicit in the human rights violations refugees and migrants are almost certain to face once back in Libya.”

The chances of dying in waters off the Libyan coast have significantly increased since 2017; a leaked EU report admitted that “conditions for migrants in Libya have deteriorated severely”; and Libya has ignored the EU’s half-hearted calls to halt the arbitrary detention of migrants. Despite all this, the deal between Italy and Libya was renewed in 2019 with the EU’s full support.

Despite evidence that Libya is rife with militia groups and human traffickers who kidnap, extort, and torture migrants, multiple EU-backed pacts that aim to halt “illegal migration” have made Libya the de facto border patrol for Europe.

Malta recently followed Italy’s lead, surreptitiously striking a deal with Libya, in which Malta’s armed forces will coordinate with the Libyan coast guard to intercept migrants heading toward Malta and return them to Libya. Meanwhile, Spain has long maintained border fences in Morocco to ensure migrants don’t make it to the aforementioned Spanish enclaves of Melilla or Ceuta – a tiny piece of Europe on the African continent.

Europe isn’t alone in playing fast and loose with the lives of migrants. Australia is a clear example of the violent lengths to which a country will go to shield itself from newcomers. Twenty-eight years ago, it introduced mandatory detention for those seeking entry without a visa. Today, it has a full-blown extraterritorial detention system on the islands of Nauru and Manus, serving as the front line for its border policing measures against migrants. Australia has even declined New Zealand’s offer to resettle up to 150 refugees per year, because such an arrangement could open “a back-door way” into Australia.

The U.S. has used its economic leverage to outsource migration enforcement to Mexico. Under the Migrant Protection Protocols (MPP), also known as the “remain-in-Mexico” program, if a migrans somehow finds a way to launch a refugee claim in the U.S., they are now pushed back to increasingly dangerous border towns in northern Mexico while they wait for their cases to be decided by U.S. immigration courts. The program originally only applied to one region in Mexico, but under threat to levy tariffs on goods exported to the U.S., the Mexican government agreed to expand the MPP to other border communities.

Migration diplomacy isn’t exclusively between the Global North and South, though – wealthier countries negotiate among themselves as well. For five years, the EU has used the Schengen Area as a bargaining chip with Croatia, dangling membership like a carrot, so that Croatia will tighten its borders and stop migrants from coming into the EU. In an attempt to convince the powers that be that it can effectively “manage” the bloc’s external border, Croatia has turned its own borders into a waking nightmare. There are countless reports of Croatian officers beating migrants, stealing belongings, refusing to hear asylum requests, and pushing migrants back to Bosnia or Serbia. The evidence of Croatia’s brutality toward migrants is staggering, yet the EU continues to praise and fund the Croatian state for patrolling the EU’s longest external land border.

“Safe” is normative

Other deals are being struck between countries that dictate where people must stay while they wait for their refugee claims to be heard and to which countries people can be sent back. Countries move migrants around like a game of human hot potato – no one wants to be stuck with them at the end of the day.

For years, countries have used “safe third-country” agreements to shirk their responsibilities. These agreements are a diplomatic tool that require individuals to launch their refugee claim in any country deemed “safe” that they pass through on the way to their destination. As a result, countries can kick migrants out simply for having passed through another country that has been arbitrarily declared safe. This practice allows countries to stymie refugee flows without technically violating the principle of non-refoulement, which stipulates that countries cannot return asylum seekers to a country where they would risk persecution.

Creating the Dublin Regulation in 1990, Europe has long followed the “safe third-country” model and systematized the practice of human hot potato. Under the regulation, it sends back migrants to the first EU country they entered, consigning them to countries with inadequate reception conditions and lesser capacity to process claims in accordance with international standards.

Today, the line is slowly being pushed further and further on which countries can be considered safe.

Canada and the U.S. have a similar deal, the Safe Third Country Agreement, which prohibits an individual from launching a refugee claim in one country if they have journeyed through the other. Human rights organizations have argued for years that the U.S. cannot be considered “safe” under international refugee law.

Today, the line is slowly being pushed further and further on which countries can be considered safe. In November 2019, the Trump administration brokered a series of agreements with Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras – countries from which some of the largest numbers of refugees flee – in which migrants are required to apply for protection in those countries as they journey to the U.S. The U.S. is already sending migrants back to Guatemala – where Indigenous people and women, among others, face extremely high rates of deadly violence – plainly violating its international obligations to not return asylum seekers to persecution.

In September 2019, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the country can deny asylum to anyone who has crossed a third country en route to the U.S. Though initially resistant, Mexico is now denying migrants free passage through its territory, using military police to stop any movement. Migrants are stuck in dangerous border towns in Mexico, caught between the U.S.’s airtight asylum policies, Mexico’s compliance, and an ever-increasing apathy toward people on the move. In practice, this bans asylum claims at the U.S.-Mexico border for all nationalities except for Mexicans, blessed by geography, who do not have to travel through another country to reach the U.S.

Back-scratching and blackmailing

Migration diplomacy is a two-way street. Wealthy countries use their money to fend off migrants, and host states attempt to leverage their migrants for material gain.

Jordan, Lebanon, and Turkey have each leveraged their population of Syrian refugees for political advantage. In 2016, when Turkey agreed to keep its Syrian refugees inside its borders, the EU gave Turkey an unprecedented sum of €6 billion for migrant programming, as well as a promise to lift visa requirements for Turkish citizens wanting to enter the EU. In 2010, the EU paid Libya €50 million after then-Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi threatened to “turn Europe black” if he didn’t get a significant sum of money. In 2015, Greek foreign minister Nikos Kotzias threatened that if Greece was forced out of the eurozone, “there will be tens of millions of immigrants and thousands of jihadists” flooding western Europe.

In 2015, Lebanon declared that all Syrian refugees over 15 years old were to pay a US$200 annual renewal fee to the state – an exorbitant amount given that 70 per cent of Syrian refugees in the country live below the poverty line. Ugandan officials, in collusion with staff from the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees and the World Food Programme, inflated the number of migrants Uganda was hosting as a means to defraud millions of dollars in aid.

Refugees as rent

At first glance, deals struck between countries may seem like a positive development if they can provide host countries with the means to support large populations of forcibly displaced persons. But we need to pull back the layers and examine the underlying framework because at their core, these arrangements treat migrants as commodities. They embolden host countries to consider displaced populations as a resource – or, more aptly, a source of economic “rent.”

As wealthy countries give economic incentives to countries of first asylum in exchange for their continuing to host migrants, we set the stage for “refugee rentier states.”

The political economy term rent refers to excess payments when there is no cost of production. Originally, this referred to “rentier states” who derived a big chunk of their national revenue from the sale of natural resources like oil. But now we see migration deals transform refugees into a source of rent. As wealthy countries give economic incentives to countries of first asylum in exchange for their continuing to host migrants, we set the stage for “refugee rentier states.”

According to political scientist Gerasimos Tsourapas, as the process of seeking asylum is demonized and woven into “crisis” narratives, it is imperative that we pay attention to how Western states aim to securitize migration flows. We must examine “refugee rentierism” because political analyses are incomplete if they do not consider forced migration a tool of diplomatic negotiations and leverage.

Now or never

In human history, demand for asylum has never been so high, but the willingness of countries to provide refuge is evaporating. States have orchestrated advanced systems of repulsion that have stymied the codified right to seek asylum.

We can no longer lie to ourselves; the global migration system is suffering a quiet and steady erosion. More people are dying as they cross oceans, more people are being turned away at the gates, and more people are being abandoned in dangerous and inhumane conditions.

We are already seeing the effects of climate change on migration, and it will drastically worsen in the coming years. Scientists warn that the climate crisis will expose 350 million additional people to drought and push 120 million people into extreme poverty by 2030. The waters will rise and so will the number of forcibly displaced persons.

We need a new system, because we don’t have a system at all. We have an international treaty with little clout and countries hell-bent on building walls and breaking pledges. We have piecemeal solutions, dictated by the whims of governments of the day. We have pretty words to mask oppressive policies.

We can no longer lie to ourselves; the global migration system is suffering a quiet and steady erosion.

As always, we should look to the grassroots for solutions. But it’s not just about welcoming people who arrive at our door; their struggle begins long before they set foot on our soil. Understanding how the global migration system works is the first step to dismantling it and starting anew.

There are organizations in Canada already examining and challenging migration’s big picture. No One Is Illegal has posted factsheets on the rights of migrants at the Canada–U.S. border and has fought inhumane immigration detention in the U.S. On two separate occasions, the Canadian Council for Refugees, Amnesty International Canada, and the Canadian Council of Churches challenged the U.S.-Canada Safe Third Country Agreement. All recognize that advocating for migrants in Canada must include halting harmful policies that extend far beyond our borders.

The walls are being built, the boats are being turned away, and the laws are being drafted. It’s time to acknowledge this destruction and to join organizations like these to fight this system.

Our children will ask us, “what did you do when they built the walls?”