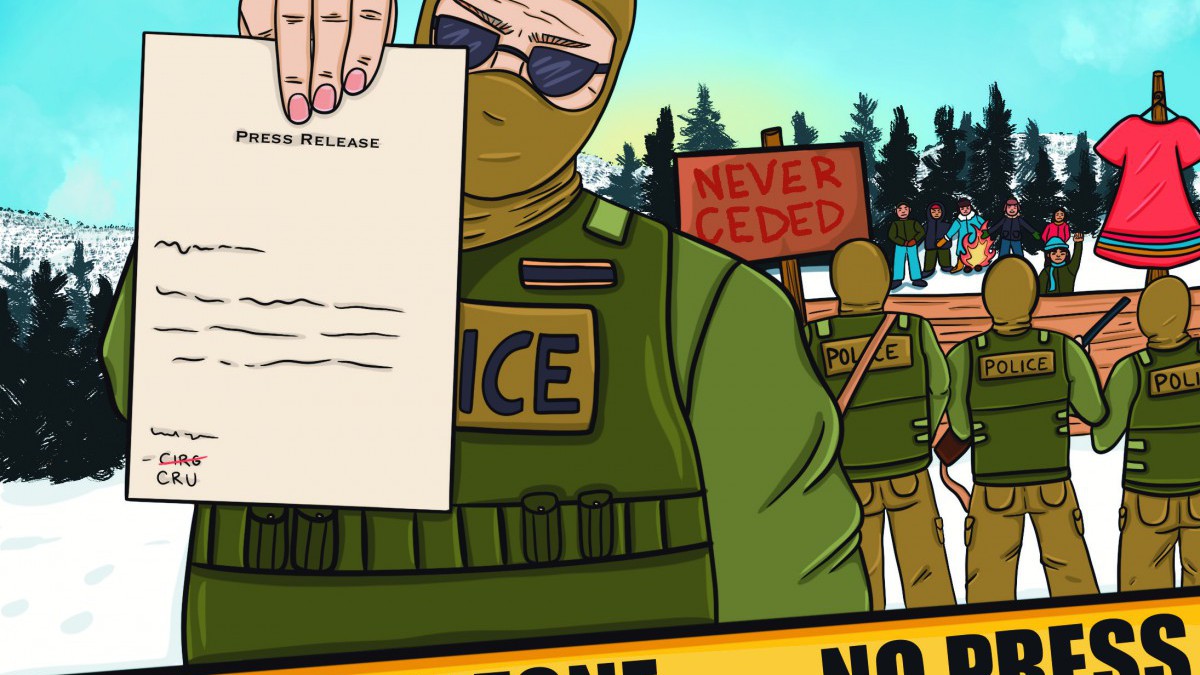

On November 18, 2021, a group of Indigenous women, men, and Elders stood together on a cold and snow-covered logging road in Wet’suwet’en territory, near Houston, B.C. Unarmed, they announced they were peaceful and would be conducting ceremony. By mid-morning, a heavily armed, militarized group of RCMP officers called the Community-Industry Response Group (C-IRG) had moved in to clear the way.

The land defenders, who were there to peacefully protest the Coastal GasLink pipeline, lined up to face the row of officers who had with them canine units and assault rifles, ready to enforce Coastal GasLink’s injunction. Logan Staats, a musician and land defender from Six Nations, was violently arrested during this encounter, along with 14 others.

Staats, describing his arrest, explains how he was roughly shoved to the ground, hitting his head. As his ear bled and his hands were restrained behind his back, multiple officers tried to grab at his face and his hair. On the sidelines, he says, “dogs were literally jumping and getting held back by their leashes. It takes a toll on someone. It makes you feel like you are about to get attacked by dogs.”

The RCMP press release that swiftly followed the enforcement claims excessive force was not employed while arresting land defenders and that “attack” dogs were only at the site “in an observation capacity.”

“I think it was nine guys we counted on top of me at one point. How can you say that that’s not excessive force? I walked away from that situation bleeding.”

Staats disagrees. He is clear that excessive force was most certainly employed, and the dogs did much more than observe. “Whether or not dogs were unleashed, they’re still there trying to get off their leashes, drooling at the opportunity to attack us. [...] They weren’t just there to observe. They were there to intimidate us.”

He adds, “I think it was nine guys we counted on top of me at one point. How can you say that that’s not excessive force? I walked away from that situation bleeding.”

This discrepancy between the account of a land defender and the RCMP press release is not isolated to Staats.

“WITHOUT INCIDENT”

Fairy Creek, located on Pacheedaht Territory, was another protest site in which the C-IRG were involved – this one against old-growth logging. On September 9, 2021, 71 land defenders were arrested. In a series of interviews with me, conducted from 2021–2022, land defenders describe their experiences. During their arrests, land defenders described experiencing a broken thumb, cracked ribs, superficial injuries, being dragged by the hair, and psychological trauma.

Once again, the RCMP press release refers to arrests being made “without any major incident or report of injuries.”

Similarly, a June 2021 press release from Fairy Creek states that “[t]here have been no complaints or reports of any injuries” during arrests. Meanwhile, there were more than 250 formal complaints over police misconduct at Fairy Creek. Among the reports and allegations include C-IRG officers hitting, punching, ripping hair, and choking land defenders who were blocking the road.

There is no alternative record of this violence other than the press releases, as media were moved to a restricted zone out of sight, 100 feet away.

[W]e need to pay close attention to how public institutions like the RCMP are employing press releases to hide, deny, and normalize ongoing colonial violence.

The C-IRG was formed in 2017 to respond to Indigenous-led resistance to resource extraction projects. The group receives funding from both provincial and federal governments to do this work.

In my previous articles on the C-IRG published by Briarpatch in 2021 and 2022, I focused mostly on the C-IRG’s violence and coercion, and other forms of wielding colonial power in tangible ways. Now, I try to understand how the RCMP’s insidious use of language works to normalize and justify their colonial violence to the Canadian public.

MEDIA AND PRESS RELEASES

The media is essential to the functioning of a democracy. It is meant to tell us what goes on in places outside of our local environment, to keep a watchful eye on the government and public services. We also rely on it to keep us informed about the environment, industry, and anything relating to public interest. Good reporting works to uncover truths and provide a comprehensive story.

A press release is an official statement typically written by an organization’s public relations team or corporate communications team to provide basic information to the public. While journalists may use these as starting points for news stories, by design, they only tell one side of the story.

[T]here are distinct ways that police in Canada exercise power to uphold extractive, colonial capitalism. One such way is through narrative power.

Given the critical role press releases and media play in shaping our understanding of current events, we need to pay close attention to how public institutions like the RCMP are employing press releases to hide, deny, and normalize ongoing colonial violence.

CONTROLLING THE NARRATIVE

As described in Jen Gobby and Lucy Everett’s chapter in the 2022 book Enforcing Ecocide: Power, Policing & Planetary Militarization, there are distinct ways that police in Canada exercise power to uphold extractive, colonial capitalism. One such way is through narrative power. They describe this as power that “can be wielded through words, framings, concepts; by the ways notions ‘normal,’ ‘acceptable,’ ‘justified,’ a ‘threat,’ etc. are constructed.”

In an example of a narrative power move, the C-IRG rebranded themselves as the Critical Response Unit-BC (CRU-BC) on January 1, 2024. Dropping the word “industry” from their name makes them seem unconnected to corporate interests. In reality, as the CBC reported in April 2024, the change comes after the C-IRG being “[d]ogged for years by complaints, lawsuits, alleged civil and Indigenous rights violations and now an ongoing federal investigation.”

The RCMP has come under fire for its heavy-handed responses at Fairy Creek and on Wet’suwet’en territory – so much so that the Civilian Review and Complaints Commission has launched a system-wide investigation into the C-IRG. Issues of excessive violence, extensive exclusion zones, and limited media access have been widely reported.

In his decision (since overturned) to rule against forestry company Teal-Jones’ application to renew their injunction at Fairy Creek in 2021, B.C. Justice Douglas Thompson noted, “the media’s right of access continues to be improperly constrained.” He also rebuked the officers for not wearing their name tags or badge numbers. As people granted authority, his decision stated, “We identify ourselves. Accountability requires it.”

During the three major RCMP raids on Wet’suwet’en territory, the police established “exclusion zones” to heavily restrict individuals such as land defenders and journalists from accessing the territory. While industry, Hereditary Chiefs, and elected council members were allowed through, these exclusion zones prevented media oversight and therefore, police accountability.

According to the RCMP, checkpoints to decide who was allowed access were necessary to prevent “further escalation” and “mitigate safety concerns.”

Sleydo’ (Molly Wickham), a Wet’suwet’en wing chief, recounts, “In one particular case, during the occupation of the Coastal GasLink drill site also known as Coyote Camp, our most highly respected hereditary house Chiefs were threatened with arrest, and we [were] surrounded by police officers.”

After witnessing and experiencing continued C-IRG violence first-hand, I became interested in investigating how the RCMP frames and justifies their actions. To do so, I partnered with Research for the Front Lines, a grassroots organization that supports the research needs of movements and communities fighting for climate and environmental justice across so-called Canada.

Together, we dug through 90 RCMP press releases from RCMP enforcement at Fairy Creek and on Wet’suwet’en territory and compared these with testimonies and video documentation of land defenders’ lived experiences.

Our analysis uncovered many examples of RCMP press releases as highly misleading and filled with contradictions and omissions. There were, of course, the frequent uses of “without incident” to describe arrests that the existence of numerous defenders’ complaints seems to contradict. Additionally, the press releases were rife with language that paid lip service to Indigenous sovereignty while emphasizing the RCMP’s measured approach and concern for public safety.

PAYING LIP SERVICE TO INDIGENOUS RIGHTS AND SOVEREIGNTY

The press release that came out the day after the first violent raid on Wet’suwet’en territory in 2019 states, “The RCMP respects the Indigenous rights and titles in B.C. and across Canada.” C-IRG’s actions on the ground – enforcing colonial injunctions through the violent raid – sent a different message, one that blatantly contradicts any notion of reconciliation or respect for Indigenous rights.

Peaceful resolution, it seems, can only occur if those looking to protect their lands and waters stand down. Standing down, though, means continuing to let industry and government proceed no matter the cultural or environmental costs.

In August 2021, the RCMP invoked Indigenous rights and title to justify the removal of land defenders at Fairy Creek, claiming, “[t]he RCMP’s priority at the moment is to provide members of the Pacheedaht elected and hereditary leadership access to their territory, which they have not been able to in the year since protesters have set up their encampments in these areas.”

This supposed enforcement of Indigenous rights in one place – Fairy Creek – was made within the context of continuous violation of Indigenous rights in another – Wet’suwet’en.

Sleydo’ (Molly Wickham), a Wet’suwet’en wing chief, recounts, “In one particular case, during the occupation of the Coastal GasLink drill site also known as Coyote Camp, our most highly respected hereditary house Chiefs were threatened with arrest, and we [were] surrounded by police officers.”

More than once, Sleydo’ witnessed the C-IRG allowing industry access to Wet’suwet’en land while refusing it to Wet’suwet’en people. The RCMP’s supposed dedication to reconciliation, she notes, is “thinly veiled,” adding, they “are only using Indigenous rights [when it works] to their advantage.”

VIOLENT POLICE AS PROVIDERS OF SAFETY?

At both Fairy Creek and Wet’suwet’en, the RCMP frequently referred to safety as a top priority. They enforced this through continuous roving patrols. On many occasions, they emphasized their prioritization of the safety of land defenders being extracted during raids.

Despite this supposed commitment to safety, the RCMP have been criticized for their unsafe practices in extracting people. Some of their methods have included lowering a 17-year-old from a protest tripod with nothing but a rope tied around their waist; attempting to use a chainsaw to lower a tripod, which resulted in two land defenders crashing to the ground; and operating jackhammers and excavators inches away from land defenders’ heads while attempting to extract them from trenches and sleeping dragons.

By labelling them as “contemnors,” the RCMP had already presumed (and conveyed to the public) the land defenders’ guilt, even though no charges had been laid at the time that the press release was published, nor after.

The RCMP often paint land defenders as safety threats to themselves and others. Press releases accuse Fairy Creek land defenders of committing “egregious safety violations” and condemn the “level of violence and disregard for safety shown by these contemnors.”

Another press release similarly refers to them as “contemnors” that had “jeopardized the safety and wellness” of Coastal GasLink workers. By labelling them as “contemnors,” the RCMP had already presumed (and conveyed to the public) the land defenders’ guilt, even though no charges had been laid at the time that the press release was published, nor after.

Despite this narrative of endangering the safety of others and themselves, the Fairy Creek and Wet’suwet’en movements have explicitly stated their commitment to non-violence. Even B.C. Supreme Court Justice Thompson states: “[The protesters] are respectful, intelligent, and peaceable by nature. [...] The videos and other evidence show them to be disciplined and patient adherents to standards of non-violent disobedience. There have only been occasional lapses from that standard.”

A "MEASURED APPROACH"

Some press releases attempt to counter claims of the RCMP’s violent tactics by emphasizing their “measured approach” to protests at Fairy Creek and on Wet’suwet’en territory.

[T]he shift toward the rhetoric of a “measured approach” has happened alongside a rise in coercive measures and militarization of the police, including increased surveillance, use of tactical troops, and “less lethal” weapons.

Since the 1990s, police in Western countries have shifted to adopting a “measured approach” to policing protests that emphasizes the use of officers trained in negotiation and respect for the right to peaceful protest.

Academics like Tia Dafnos, though, have noted how the shift toward the rhetoric of a “measured approach” has happened alongside a rise in coercive measures and militarization of the police, including increased surveillance, use of tactical troops, and “less lethal” weapons.

Arrests made in November 2021 – the same raid that resulted in Logan Staats’ arrest – involved the use of excessively violent weapons, namely canines and tactical military weapons used by snipers. The RCMP dismissed these claims of military weapon involvement as mere equipment choices due to the “unpredictable nature of what [they] could be facing” in a remote, heavily forested area.

If, as in the case of Wet’suwet’en land defenders, claims of mistreatment and police violence are denied by the RCMP, it begs the question: how does the RCMP define an “incident” or a “measured approach?”

When asked by Briarpatch to provide comment on how the RCMP defines incident and excessive force, staff sergeant Kris Clark emphasized the RCMP’s commitment to a measured approach and noted medics were provided on site for those who required attention. Clark stated, “ I would like to emphasize that the majority of arrests [at Fairy Creek] took place without incident after significant hours of either negotiations or careful and slow actions to remove individuals from various obstacles.”

When pressed for a concrete answer on how the RCMP determines “incident” and “measured approach,” Clark provided dictionary definitions.

Regarding what is deemed an excessive or necessary use of force, he says, “Section 25 of the Criminal Code provides the police with the authority to “use as much force as is necessary” in the administration of their duties. [ ... ] Excessive force is defined in Section 26 of the Criminal Code as, ‘Every one who is authorized by law to use force is criminally responsible for any excess thereof according to the nature and quality of the act that constitutes the excess.’ What is deemed ‘necessary’ or ‘excessive’ is determined by the courts.”

By denying “incident,” press releases effectively erase the use of violence, painting a distorted view of what happened and misleading the public.

Given the remote, rural locations of many of these struggles and given the C-IRG’s frequent use of media exclusion zones, the RCMP’s version of the story is often the only story being heard. Their press releases heavily influence how the Canadian public understands what is transpiring and what is at stake.

Bringing all these press releases together and comparing them to the first-hand experiences of land defenders helps to expose the RCMP’s blatant attempts to control – or at the very least confuse – the narrative of what is happening on the ground.

SLIPPERY, COVERT VIOLENCE

As C-IRG has morphed into CRU-BC, this close attention to narrative power will be critical. CRU-BC is now being called to other protests in B.C., including ones relating to Palestine solidarity (already deemed “pro-Hamas” protests by the RCMP).

The use of narrative power to justify policing goes beyond B.C. and beyond the RCMP.

Echoing the many RCMP press releases, we see McGill using this same narrative of safety to justify the policing and removal of protesters and dismantling of protest camps.

On May 10, 2024, McGill president Deep Saini sent an email update to the McGill community regarding the Palestinian solidarity encampment taking place on campus. The letter explained that the university was “seeking a court order that would require those participating to dismantle the encampment. [...] The order would authorize the Montreal police (SPVM) to enforce it.”

In this letter, Saini cited safety as the main reason for the court order and policing, writing that “[t]he University is concerned about the risks that the encampment poses to the safety, security and public health of members of the McGill community and for those participating in the encampment.”

Echoing the many RCMP press releases, we see McGill using this same narrative of safety to justify the policing and removal of protesters and dismantling of protest camps. To evoke the very human need for safety and security to justify the policing of Palestine solidarity, while ignoring the unfathomable genocidal violence happening in Gaza, is unconscionable but, unfortunately, not uncommon.

It’s not anti-pipeline blockades and solidarity camps that need to be taken down. It is the settler-colonial, capitalist systems that need to be dismantled, along with the slippery, covert ways these violent systems are justified and normalized day after day in Canadian media.

*We would like to acknowledge the support of Research for the Front Lines coordinator Jen Gobby and volunteers Dorothy Settles and Adela Agnew for valuable help with this research and article.

**Correction, July 26, 2024: This article has been corrected to specify that the interviews with land defenders took place with Molly Murphy, and not Research for the Front Lines, as previously stated.