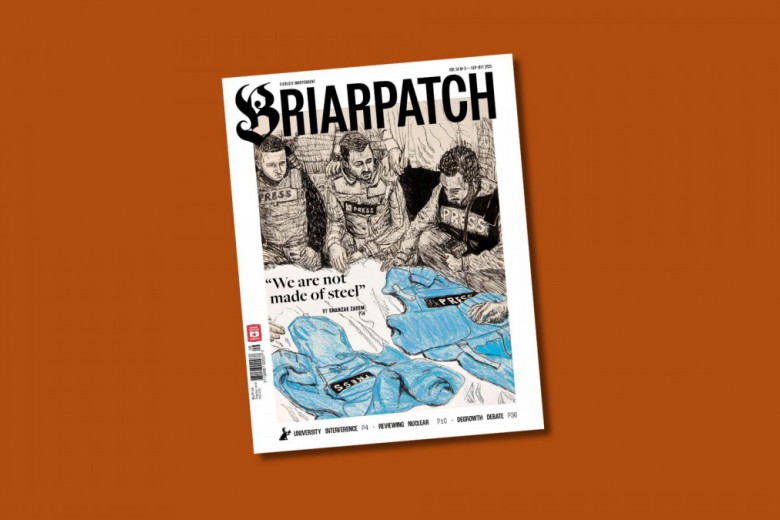

“A working day in Gaza for a journalist feels like waiting to be executed on the gallows.” This is how 27-year-old photojournalist Salama Nabil Younis describes the brutal reality he faces each day. For front-line journalists like him, reporting from Gaza isn’t just a professional challenge – it’s a psychological, emotional, and existential burden.

Younis earned his bachelor’s degree in media from Al-Aqsa University in Gaza City, where he began his career in photography and editing. Before the war, he focused his lens on documenting life: weddings; community festivals; youth programs; and the vibrant beauty of the Gaza coastline. “I wanted to show the beauty of our place,” he tells me. “The sea, the celebrations, the nature. We love life.”

But since the escalation of violence in October 2023, everything has changed.

“We live through very frightening circumstances,” he says. “There’s a lot of bombing. We lack even the basic necessities of life. Still, we must find a way to make our voices heard.”

These targeting patterns have made Gaza one of the most dangerous places in the world to be a journalist, particularly for those working independently or without the protection of major international outlets.

He now works as a photojournalist for the Turkish Anadolu Agency and several local media outlets in Palestine. The nature of his work has fundamentally changed. Gone are the days of staged photo shoots and joyful ceremonies. Now, he captures destruction, mass displacement, and death – on a phone. With his laptop and camera destroyed in an airstrike, and no access to replacements, Younis does everything on his mobile device: filming, editing, and sending files to agencies, often with great difficulty.

A family displaced from Al-Maghazi camp after Israel issued evacuation orders. They are pictured with a number of their belongings on a wagon. Photo by Younis.

Journalists in Gaza are not collateral damage – they are deliberate targets. “We journalists are directly targeted,” he says. “The occupation beats us, wounds us, threatens us, and kills us. There is no immunity.”

In the six months following October 7, 2023, more than 100 Palestinian journalists have been killed in Gaza, according to Reporters Without Borders. Many more have been injured, displaced, or psychologically broken. The targeting of media workers by Israeli forces has been widely condemned by international press freedom organizations, yet the violence continues.

This is not the first time journalists in Gaza have faced grave danger. During the 2008-2009 war, known as Operation Cast Lead, at least six media workers were killed, and dozens more were injured or detained. In the 2014 conflict, the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) documented at least seven Palestinian journalists killed in Israeli airstrikes, including some while reporting from clearly marked press vehicles. These targeting patterns have made Gaza one of the most dangerous places in the world to be a journalist, particularly for those working independently or without the protection of major international outlets.

“We are not superheroes. We are not made of steel. We are afraid every second,” says Younis. “We cry. We live in terror.

But while these deaths make international headlines, the deeper, longer-term psychological trauma remains largely invisible. What is it like to live every moment expecting to die? What does that do to a person’s sense of safety, purpose, and humanity?

The toll of war reporting

Anthony Feinstein, a professor of psychiatry at the University of Toronto, has spent decades researching these very questions. His work on the mental health of war correspondents is foundational and captured in his book Journalists Under Fire: The Psychological Hazards of Covering War. Through extensive clinical studies, Feinstein has identified a broad range of psychological risks for journalists in conflict zones: PTSD, anxiety, depression, substance abuse and moral injury.

In a 2002 study published in the American Journal of Psychiatry, Feinstein and his co-authors found that nearly one-third of war correspondents developed post-traumatic stress disorder, with even more showing symptoms that impaired daily functioning. Repeated exposure to extreme violence, trauma, and personal risk corrodes mental stability over time.

“We are not superheroes. We are not made of steel. We are afraid every second,” says Younis. “We cry. We live in terror.”

Feinstein also emphasizes the ethical weight that journalists bear during conflict reporting. In Journalists Under Fire, he explores how moral injury can emerge not only from witnessing atrocities but from being unable to intervene. This helplessness – observing children dying, families being bombed, communities displaced – without the power to stop it, creates a distinct kind of trauma. Journalists are trained to observe and report, not act, but in humanitarian catastrophes like Gaza, the line between professional duty and human compassion becomes increasingly blurred.

Displaced girls inside the Iwa school form a dabke group and perform during a festival at the school. Photo by Younis.

Feinstein notes that freelance war journalists are prone to developing acute PTSD symptoms – nightmares, emotional numbness, hypervigilance – but may recover significantly after receiving counselling, taking time away from assignments, and undergoing structured debriefings. This indicates how significant the presence of post-conflict care is. By contrast, journalists in Gaza face similar or worse levels of exposure without any of the psychological scaffolding Feinstein identifies as essential for recovery. The absence of support structures turns treatable trauma into chronic suffering.

No safety net for Gaza’s journalists

Life under siege has compounded the trauma. Gaza has been under Israeli blockade since 2007. Movement is restricted. Electricity and water are unreliable. Basic services – let alone mental health care – are in short supply. “We are conveying people’s stories, hopes, pain, and ambitions,” Younis says. “But the world does not visit us, and we do not visit it. We are completely isolated.”

According to the World Health Organization, “Gaza faces a critical shortage of mental health professionals, with less than one psychiatrist per 100 000 people pre-conflict, worsened by war casualties and displacement.” Mental health services have been chronically underfunded and understaffed for years, a situation made worse by repeated bombardments, displacement, and the long-term effects of blockade. In this environment, journalists suffering from trauma often have nowhere to turn for professional support.

For journalists working for international news agencies, trauma is often mitigated by institutional support: therapy, debriefs, leave. But for freelance journalists in Gaza – who make up a significant portion of the press corps – these protections are non-existent. There are no trauma response teams, no clinical psychologists, no days off.

“Every story we cover affects us deeply,” Younis says. “We live it. We see it. We feel it.”

He describes walking for hours just to find a working power outlet or a patch of internet signal to file a report. He often sleeps in borrowed spaces, sometimes on the street. His work is conducted while under the constant threat of airstrikes, with no assurance he’ll survive the day.

“I was homeless, hungry, injured, and I had lost all my dreams. But every day, I felt compelled to continue,” he says. “I try to help my people with the only thing I know – telling their stories.”

“I want to stop filming destruction, tears, and screams. I want to film nature. Seas. Mountains. People laughing,” he says. “That’s what I want to do with my life.

Younis continues to resist despair. He is currently enrolled in a master’s program in media at Al-Aqsa University – while the university has been destroyed, many students are navigating online study. He studies English in his spare time, and has recently resumed editing projects for international clients. “I want to leave Gaza and live a beautiful life. I am preparing for that day,” he says. “I’m learning advanced editing, graphics, scriptwriting – anything that keeps me dreaming.”

Purpose as a shield

Feinstein also notes that many journalists in war zones view their work as morally purposeful, which can serve as a buffer against psychological harm. In Journalists Under Fire, he writes that reporters who frame their experiences through a sense of mission or moral responsibility are often able to maintain a sense of coherence amid chaos. This psychological anchoring can reduce the risk of long-term trauma. For journalists like Younis, who speak of storytelling as a duty to the oppressed, that moral framework may be one of the few remaining forms of protection.

Despite everything, Younis remains committed to telling the truth. “Many times, I have thought about quitting,” he says. “I’ve wanted to stop filming blood and rubble. But there is no safe place here. Even at home, we are not safe. The war finds us wherever we go.”

Younis (middle) at a camp for displaced families in the Deir Al-Baleh area. Courtesy of Younis.

His dream is to return to storytelling – not of war, but of joy.

“I want to stop filming destruction, tears, and screams. I want to film nature. Seas. Mountains. People laughing,” he says. “That’s what I want to do with my life.”

In the final minutes of our interview, his tone changes. It becomes softer.

“Tell the world that we are people with hearts. We are not made of steel. We are afraid every second. We want the war to stop. Please, tell them not to forget us.”

*This interview was conducted in Arabic and translated by the author.

_copy_780_520_s_c1.png)