“Some of the worst racists carry a gun, and they carry a badge authorized by you, Commissioner Paulson, to do the work. We need you to confront racism in the ranks.”

Grand Chief Doug Kelly, leader of the Sto:lo Tribal Council from unceded Coast Salish Territory in British Columbia, delivered this indictment to RCMP commissioner Bob Paulson on December 9, 2015, at the annual meeting of the Assembly of First Nations. He was referring to the everyday racism faced by Indigenous peoples at the hands of the RCMP, and he pushed the commissioner to take action on racism in his ranks.

“Shame on you, Mr. Paulson,” Grand Chief Kelly pressed. “You want to earn trust? You start by owning the truth, and apologizing. And doing more than apologizing. You start acting on the direction of government about reconciliation.” The grand chief admonished the RCMP, which will assume a central role in the coming months as the new federal government takes aim at a massive overhaul of the justice system while laying the foundation for a national inquiry into missing and murdered Indigenous women.

The RCMP commissioner then took the stage. “I hear what you say,” he said. “I understand there are racists in my police force. I don’t want them to be in my police force.”

Paulson urged the audience of Indigenous leaders to “have confidence in the processes that exist, up to and including calling me if you’re having a problem with a racist in your jurisdiction.” He assured the audience that the RCMP has “elaborate systems to bring accountability to those people who are … empowered to deliver policing services.”

I want to scrutinize his response, which emphasized the singular nature of the racism in the RCMP. This exchange, at this particular political moment in Canada, is embedded in a much bigger discussion – one that needs to be unsettled.

Events like the encounter between the grand chief and the RCMP commissioner offer critical opportunities to look at the ways in which racism is framed. The language can often involve premature gestures of resolution. Systemic issues are not issues of immediate resolution.

Rather, they demand that we pause and deliberate. Premature, rushed solution-seeking can distract us from the real work at hand, which is messy, troubling, and difficult work. I write this as a settler living in Treaty 4 Territory. From my perspective, a discussion about racism in policing cannot be a simple matter. It requires a willingness to discuss settler colonialism and systems of oppression and privilege.

Resetting the scene

After six years of investigating the sexual, physical, and emotional abuse in government-funded residential schools, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) released its full recommendations in 2015. The report, unprecedented in its scope and findings, importantly locates residential schools in the contemporary matrix of settler colonialism, including poverty, incarceration, and violence. Of note, recommendations 25 to 42 explicitly focus on the justice system and call for reform at the local, provincial, and federal levels.

In December 2015, the newly elected Liberal government committed to implementing the TRC’s 94 recommendations, and announced a national inquiry to investigate missing and murdered Indigenous women. Many people speculated that change was afoot.

Meanwhile, the CBC announced that it was closing down all of its comment fields associated with stories about Indigenous peoples. The broadcaster indicated that these specific fields have become overwhelmingly filled with such “hateful and vitriolic” racist comments that the news outlet temporarily suspended any commenting.

It was this backdrop of news that framed the report about RCMP commissioner Bob Paulson’s response to Grand Chief Kelly’s indictment of the RCMP.

What Paulson suggested, behind his conciliatory tone at the meeting, was that individual acts of racism are the result of rogue racist officers; the officers’ actions could be handled swiftly with mechanisms of accountability within the police force. He did not indicate that he recognized racism as a systemic issue, nor as a direct effect of setter colonialism. Paulson spoke about isolated racism in a country where, in the broader context, the national news network had to disable the comment field on stories about Indigenous peoples because commenters consistently crossed the publisher’s decency guidelines.

Paulson agreed with Grand Chief Kelly: there are racists in the force. But, in his view, those racists are outliers; they are unwanted, they are limited, and a single phone call can solve any (infrequent) occurrence. Paulson offered a simple solution to a complex problem.

But systemic racism is not going to be solved with a phone call.

As a colonial state, Canada has built up systems that privilege settlers. Systemic racism is obscured when it is reframed as the single actions of particular individuals. This allows settlers to look for quick solutions and avoid facing the systemic nature of racism – to avoid that messy, troubling, and difficult work.

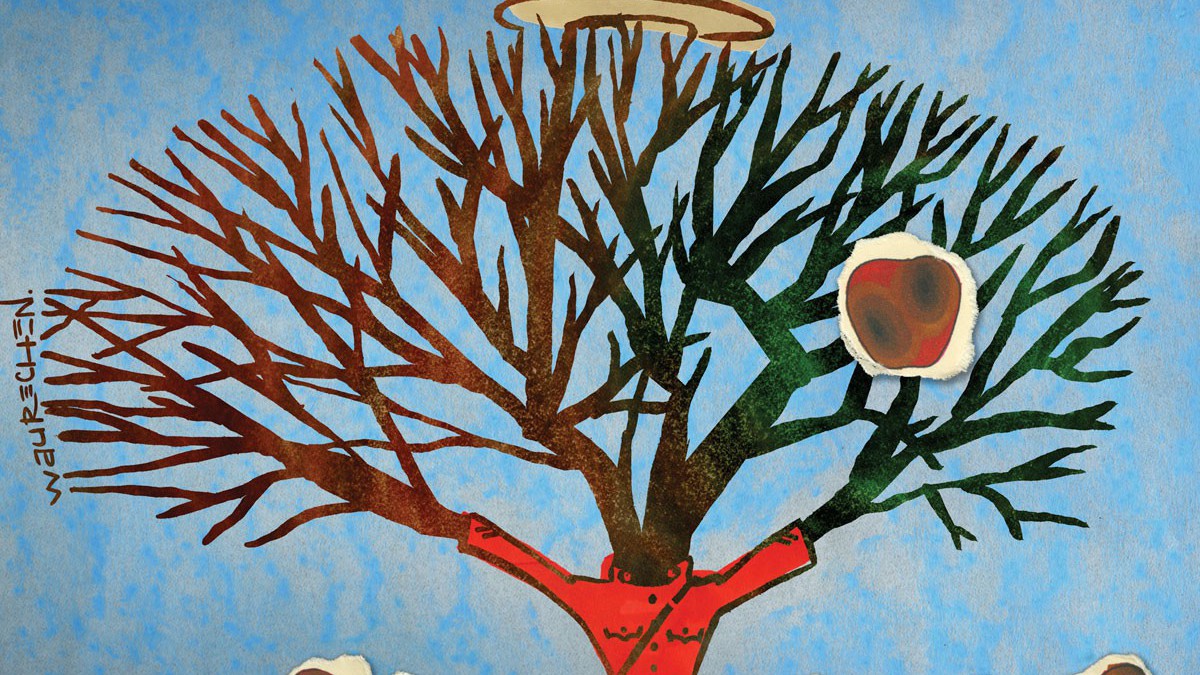

Apples or orchard?

In his speech, Grand Chief Kelly asked Commissioner Paulson, “Why do I keep dealing with these bad apples?” He observed that, within the RCMP, there were “wonderful public servants.” He also affirmed, “I love and respect those public servants.… But I’m talking about the other ones.” Kelly was fierce in naming racism in his initial critique, but he quickly hedged his bets to avoid indicting all police – only the bad apples.

The problem with the “bad apples” metaphor is that it obscures the systemic nature of racism.

We need to be able to talk about systems, not people. People make up systems, yes, but if we get lost in a discussion about the people who make up systems, we lose sight of the fact that there are systems that organize our society. If we talk about the systems, we can start to draw links to the root problems of ongoing racism and have a meaningful dialogue about important issues.

Take, for example, the fact that upwards of 80 per cent of people incarcerated in Saskatchewan are Indigenous when they only comprise just over 15 per cent of the overall population. Over 1,200 Aboriginal women and girls have been killed or are missing in Canada – and that number is actually higher, given the many more whose deaths were not investigated or who were not categorized as missing or murdered. We could discuss the massive overrepresentation of Indigenous children in the child welfare system. In Manitoba, for example, upwards of 90 per cent of the 10,000 children in state custody are Aboriginal, which has prompted the Assembly of Manitoba Chiefs to hire its own child advocate. The welfare system apprehends children from families that have themselves experienced historical state-executed traumas, including residential schools and the 60s Scoop. These are all results of systems of oppression, and these systems are much more powerful and entrenched than the individuals implementing them. Unsettling these systems demands that we do away with the “bad apples” metaphor, which erases the systemic nature of and the histories that inform actions, policies, “accountability processes,” and responses from government departments, legislative representatives, and police forces.

Oppression is not the result of a few bad apples. It is an outcome of specific systems of justice, education, health, and social services, which each uphold powerful practices that, taken together, produce particular outcomes. Systemic oppression requires a sharp instrument to dissect these systems and identify specific actions that facilitate ongoing programs of oppression. Cut open the system to identify the actions first, but don’t stop there.

The “bad apple” metaphor is propelled by ongoing complacency, apathy, and derailment tactics. It allows individuals to use the language of anti-racism to call for an inquiry or justice system reform, but it does not actively unsettle the very systems that sustain oppression. In the absence of solidarity work that unsettles entire, complex systems, settlers and others can find themselves believing that the situation in Canada is simply a case of a few bad apples. They say, “This is not my Canada,” when they read about oppression. To them, I say: “This is your Canada.” If we are stuck with the metaphor of bad apples, then Canada is an orchard that has been rotting since its colonial inception.

A version of this article first appeared on Michelle Stewart’s Changing Suns Press blog, Unsettled, on December 16, 2015.