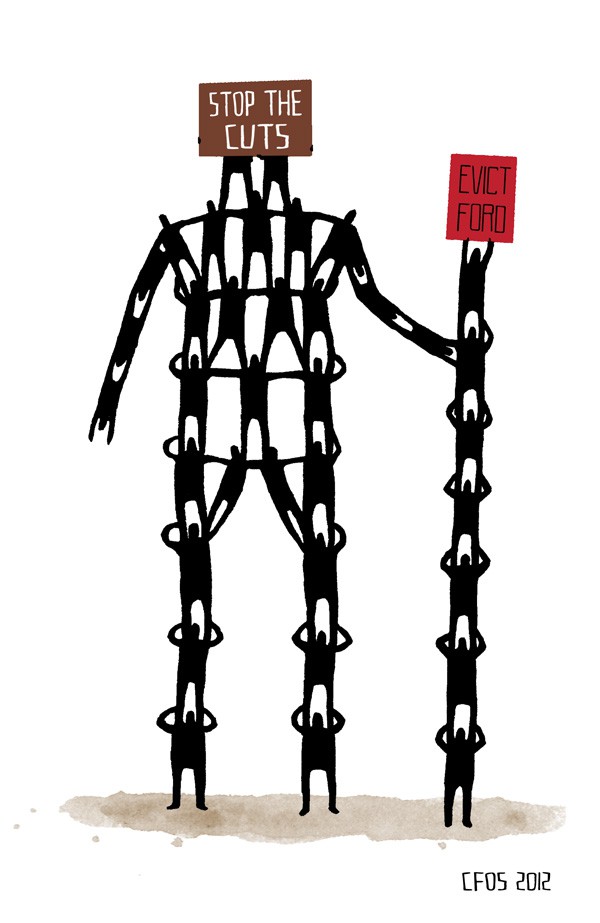

After months of mounting public pressure and protests, citywide resistance to Toronto Mayor Rob Ford’s 2012 budget succeeded in reversing $20 million in proposed cuts to social services this January. At the same time, the austerity assault continues in Toronto and across Canada with slashes to social services ranging from libraries to daycares, emergency services, and public transit. Toronto resident and health-care worker Megan Hope caught up with three community organizers at the forefront of the budget battle to discuss what made this victory possible, and what lies ahead in the struggle to stop the cuts.

Beth Wilson is the senior researcher with Social Planning Toronto, a non-profit commun-ity organization that works to advance social and economic justice issues and promote civic engagement in Toronto.

Victoria Barnett is a volunteer community worker. She co-ordinates meetings in neighbourhoods across the city with Toronto Stop the Cuts Network.

Maureen O’Reilly is a front-line librarian with the Toronto Public Library. She has been the president of the Toronto Public Library Workers Union since 2010.

Why did Toronto residents oppose the 2012 budget?

Wilson: The 2012 budget included $88 million in proposed service cuts across almost all areas of the city, including libraries, recreation, community services, arts programs, environmental programs, housing, homeless shelters, child care, transit, and emergency services. These cuts would have jeopardized public and community services for residents across the city and hit low-income communities the hardest.

In the summer of 2011, the city hired KPMG, a high-priced consulting firm, to conduct a core service review and deliver a list of recommended cutbacks. This set the stage for strong public opposition to the 2012 budget before it was even released. It was clear from the public engagement in the core services review process, which included two all-night marathon deputation sessions, that Toronto residents place a high value on our public and community services and that dismantling programs, increasing inequality, and targeting low-income communities is not part of our vision for the city.

Barnett: The 2012 city budget debate in Toronto was not about the needs of city residents, but about cutting the deficit by slashing services and presenting public workers as the problem.

The rhetoric surrounding the deficit was flawed in the first place. Ford cut from revenue-generating sources, such as the vehicle registration tax, and then claimed not to have enough money in the budget for core services. The discussion of the deficit was also based on hyperbole. We were initially told that there was a looming $770 million deficit, but by the time the dust settled, the city had a $154 million surplus.

O’Reilly: Rob Ford was elected on a mandate to cut the “gravy train” at city hall. But when KPMG delivered its recommendations, it became clear that the agenda was to really dismantle Toronto’s public services, to open the city for business, and to privatize city assets for individual gain. This would have had a devastating effect on the livability of the city, and Torontonians were incensed by this all-out attack.

Some have described the clawback of $20 million in proposed budget cuts as a victory, while elsewhere it has been described as “winning the battle, but losing the war.” What is your perspective?

O’Reilly: It was a massive victory in that these changes would not have even been contemplated months before. New political coalitions were formed, and the omnibus bill to reverse the cuts addressed many of the concerns that arose in the public consultation process. It also reversed many of the Ford administration’s directives.

When Councillor Cho’s motion to protect the library service from further cuts was passed, cheers and clapping erupted in the rotunda of city hall. In all my years of attending budget meetings, I have never witnessed such a response from the public. Clearly, the city had won that night.

In either the federal or provincial arena, such an event would have resulted in a non-confidence vote and the government would have been forced to resign and call an election. Unfortunately, this does not play out the same way in municipal government.

We have seen in recent weeks, especially in the debate over transit, that the Ford administration has lost power and authority to govern. There have been several calls for the mayor’s resignation. The budget battle was an important victory in instilling confidence that we can effect change at city hall.

Wilson: It was a major accomplishment to get city council to take tens of millions in proposed cuts off the table. When the budget was launched in November, it was not at all clear that we would be successful in moving council to save services in any significant way.

It was soon clear that library closures and cuts to student nutrition programs were not going to go through – there weren’t a lot of council members lining up to take food out of the mouths of hungry children – but it looked like most of the cuts were going to stick.

Ultimately, on the floor of city council, almost $19 million in cuts were taken off the table. That just never happens. Usually by the time a budget hits the floor of council it is mostly a done deal. In the end, while we didn’t end up with a progressive budget, communities were successful in saving vital services on account of mass mobilization on a scale that we have not seen in years.

The budget vote has also shaken up the dynamics on city council and emboldened many members of council. The mayor and his administration have been unable to move forward with selling off 10 per cent of Toronto Hydro or the mass sell-off of hundreds of Toronto Community Housing residents’ homes. City council has reasserted its position in support of expanding light-rail transit rather than the subway expansion promoted by the mayor. These recent events would have been unimaginable a few months ago. The budget vote was a significant turning point.

Barnett: In the broadest of senses, no real victory is possible in the sham electoral democracy that we live in. Until we have meaningful community control over community resources, mobilizing around budgets in the age of austerity will continue to be about fighting over scraps.

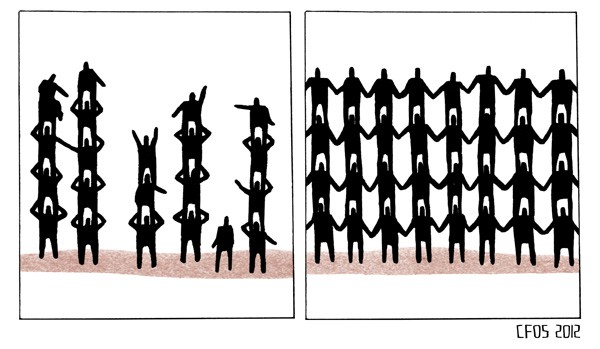

At the same time, there was a very real victory in that people from all walks of life became involved in defending their city services and demanding more. Toronto Stop the Cuts Network helped form 11 neighbourhood groups that are organizing across the city, and that is a victory. It’s a small step in building the kind of people power necessary to create real transformative change.

City councillors consistently spoke of hearing from their constituents that they opposed the cuts. Can you describe how your organization mobilized or campaigned against the proposed budget? What were some of the specific actions or steps you took in organizing against the cuts?

Barnett: The idea to form the Toronto Stop the Cuts Network emerged in a meeting between labour activists and community organizers from the Ontario Coalition Against Poverty, No One Is Illegal – Toronto, Toronto New Socialists, and others. We called a meeting of allies and developed a strategy that ran parallel to the budget consultation process.

When the city surveyed Toronto residents, we organized our own people’s poll, with organizers both standing on street corners and conducting online polls. This gave us the contacts to call meetings in a few neighbourhoods.

When the city organized meetings in different wards to talk about the budget, we organized our own meetings in neighbourhoods across the city, many of which evolved into ongoing neighbourhood groups.

When the city organized open meetings for residents, we organized our own mass meeting. Over 600 people came together, drafted a declaration from scratch, and conducted a vote among those assembled. We then distributed this declaration over email lists and on social media, gaining the signatures of over 3,000 people. Those who signed the declaration were encouraged to join an existing neighbourhood group if there was one, or to create one if there were enough people signing on from that area.

With this momentum, in addition to door-to-door community organizing and online outreach, we were able to build for a mass mobilization on September 24 when a special city council meeting was to take place to vote on the recommendations by KPMG. At the last minute, the city postponed the discussions until the actual budget vote on January 17.

On January 17, we organized a joint rally with Respect Toronto, a community/labour coalition headed up by the Toronto and York Region Labour Council. All of this culminated in the new motion that was brought to the council floor.

It is critical to note that throughout this process there were dozens of groups across the city mobilizing to defend specific services, be they libraries, community centres, wading pools, or what have you. Stop the Cuts Network was only part of this broad uprising against the mayor.

Wilson: Social Planning Toronto (SPT) has been involved in several ways. Through our city budget watch blog and email list, we have monitored and reported on every aspect of the budget process, from budget launch in November to final vote in January. We have provided analysis on the budget and promoted opportunities for community engagement. We canvassed each member of council to ask when they would be holding their local budget town hall meeting for constituents, and helped to promote these meetings widely.

We also created a map of Toronto that showed the location of service cuts and how low-income neighbourhoods would be disproportionately impacted, which caught the attention of councillors and media.

In our deputation to the budget committee, we spoke about the cuts impacting seniors, including the proposed elimination of the Hardship Fund, a city program that helps low-income seniors with serious health issues. Working with several seniors’ organizations we launched a campaign to save the Hardship Fund through the media. The Toronto Star dedicated news stories and an editorial to the topic, calling out individual councillors who had voted to consider cutting the program. In the end, the Hardship Fund was saved.

SPT always organizes an annual member forum on the city budget after it is released. This year, a panel of a dozen people working in community services, the environment, arts, and labour provided an analysis of the 2012 budget in the days following its release, which helped get people up to speed on what was an enormous and complex budget. Our staff also organized community budget forums across the city to engage local residents in the budget process.

O’Reilly: Library workers recognized at the conclusion of our collective bargaining in 2009 that greater challenges awaited us both at the municipal and at the library administration level. We knew that we had to better position ourselves to get our message out.

Fortunately we had already begun work in this area, and we were able to react quickly to the KPMG report recommending branch closures with the launch of Project Rescue and the online Love a Librarian petition, which greatly assisted us in our fight. Responses to the petition were collated based on postal address and sent as letters to the councillor for that area.

We have been told that the emails in support of the library service represented the greatest number of emails ever received on a given subject at city hall. Some councillors received over 2,000 emails from their constituents alone, and over 50,000 Torontonians signed the original petition.

Library workers also launched the My Library Matters to Me contest which featured, as the prize, lunch with one of 11 participating Canadian authors, most notably Margaret Atwood. This contest, along with read-ins, an appearance at the Word On The Street festival, and other cultural events allowed Torontonians and library workers to come together and express their mutual support for the library service.

What was effective about the mobilizations? What were the weaknesses?

Barnett: Toronto Stop the Cuts Network now has 11 neighbourhood groups that continue to organize across the city. The budget was only one step in a long journey that will include continued struggles at municipal, provincial, and federal levels. The neighbourhood groups will continue to organize, and it’s been great to see the expanding network of people committed to making change.

In terms of weaknesses, one of the primary obstacles we’ve faced has been disseminating information. Like all grassroots groups, we are run completely by volunteer labour. Ford has the media at his doorstep and the financial resources to reach out to all parts of the city whereas we have to build that power and engage people without those resources. That’s part of what we’re organizing for: community control over community resources.

Wilson: The educational work, the media work, the mapping, the ward teams, working together with residents and groups with common cause – it was all important in pushing back against the cuts. But we know this agenda of cutbacks is far from over.

There’s a lot more work to be done to engage people around the issue of contracting out and privatization, which is a major agenda of this administration. Most of the focus of discussion has been on cuts to services. It’s often easier to mobilize around the loss of a service, such as the closure of a community pool, which people can relate to directly, than it is around saving good public service jobs. It’s important for people to make the connection between good public services and good public service jobs.

O’Reilly: The amount of information that was made available to communities, outlining both the short-term and long-term implications of the budget, was invaluable in laying the foundation for change in this city.

One of the major weaknesses was the sheer number of issues that needed to be addressed and activities that needed support. This was a product of the scope of the attack levelled by the Ford administration, and I am sure it was an intended strategy on their part. There were several attempts to pit the various groups against one another and portray them as competitors, which were largely unsuccessful.

Both community and labour groups organized against this budget. How do you think community and labour groups worked well together?

Barnett: I think the important thing to note here is that labour is part of the community and the community is part of labour. We were all working together for a city that is livable, sustainable, and accommodating to all of its residents. Rob Ford and his allies were, and are, trying to take that away to please big businesses and to further enrich themselves. They tried to pit Toronto residents against labour groups, which is why it was so important for all of these groups to work together to take back the city that we want, where the needs of the residents are put before the bottom line.

Wilson: Local labour groups have done a lot of work to reach out to community and support community services under threat. Residents and community organizations are speaking out against the contracting out of public services, as labour groups take a strong stand against service cutbacks.

We have Rob Ford to thank for the opportunity to foster our solidarity and build connections between community and labour. The sheer breadth of the proposed cuts and the mass impact on a range of communities has brought us together and united us in common cause.

O’Reilly: I think there was a real coming together of labour and community groups fighting for a common good across the city. This was expressed at the most basic level of both sides coming together to share their stories. In the over 15 years that I have been involved in labour issues, this is the first time that I witnessed such a close collaboration.

What are the next steps for those opposed to service, public sector, and labour cuts?

Wilson: We have to keep organizing in our communities, and in key wards, coming together with individuals and groups with common cause to ensure that the momentum created does not die down. It would be exciting to return to a place where we are not protesting against threats to our city but rather engaging in city building where we are working toward the creation of an inclusive and equitable city for all.

Barnett: We have to continue with more outreach and more education. It’s time to make the structures we have now stronger by getting more people engaged in whichever way is most relevant to them, be it working on issues around housing, poverty, migrant justice, transit, the environment, labour, or anything else.

We need to continue building connections and building bridges across all of these issues in order to make our work more successful and to keep those in power on their toes. It’s this type of work that they don’t want us to do, and that’s why we have to keep doing it.

O’Reilly: The next immediate step for us is to oppose further labour cuts during the collective bargaining process. The loss of 107 full-time equivalency positions in the library during the budget process has been devastating. We were already facing a severe staffing shortage, and this has just added to the challenge.

We must continue our outreach in our communities and continue a dialogue focused on how to counter the austerity agenda and build the city we want to live in. We have to work hard to ensure that glib references to “gravy” don’t take hold in the future and undermine the quality of life here in the city.