In my final class studying international human rights law, I shared my paper analyzing Ukraine’s law on Indigenous people which, while imperfect, protects the territorial and language rights of Crimean Tatars, Karaites and Krymchaks. In the class discussion, a friend and self-proclaimed Marxist wearing a keffiyeh asked if I knew that the Russian language was broadly oppressed in Ukraine. Despite their rightful support for Palestine and correct criticism of colonial governments, they tended to be sympathetic to a different colonial, imperial power by repeating one of Russia’s falsified justifications for engaging in an unprovoked war of aggression.

Expanding our critiques beyond western colonial empire is important as we struggle to find alternatives to any form of oppressive, centralized power. As fascism balloons in our own backyard, we can learn from Ukrainian people actively resisting a fascist authoritarian state. And as we try to comprehend how to dismantle an empire here, we can well be reminded that the problem isn’t one empire or another; rather, the problem is empire itself. As one empire coerces Ukraine into a minerals deal, another empire is currently shooting ballistic missiles at shopping centres in Ukraine.

The following resources have helped me understand Ukrainian resistance as removing itself from under the foot of centuries of a colonial power.

Russian Colonialism 101 (2023)

Matryoshka of Lies: Ending Empire (2024)

In part, the purpose of the episode and the podcast as a whole is to allow a western audience to better understand Russian colonialism as akin to the genocidal horrors of European colonialism that many North Americans are just starting to grapple with. Similar to many radicals in North America calling for an end to U.S. hegemony and violence through an end of the American Empire, this episode suggests that a “total reset in what is now the Russian Federation” is the only way to end these continuing colonial expansionary tactics.

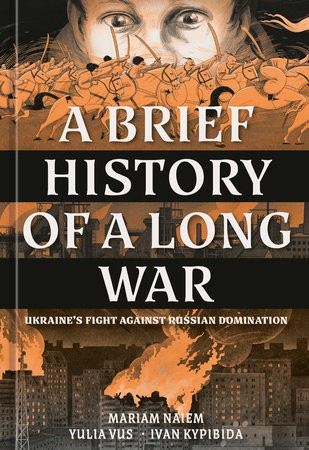

A Brief History of a Long War: Ukraine’s Fight Against Russian Domination (2025)

Whereas most narratives of the war start in 2022, or maybe 2014, Mariam Naiem’s graphic novel puts Russia’s war on Ukraine into perspective from the very beginning of Ukrainian nationhood. It unravels the long history of policies meant to extinguish Ukrainian sovereignty movements that threatened Russian control over valuable Ukrainian natural resources: from the Holodomor to policies meant to marginalize the Ukrainian language, to Russia’s invasion once Ukraine shifted into the European sphere of influence. This introduction to the history of the region helps give context to the war by explaining the centuries of Russian empire and Ukrainian resistance.

While the Western left has generally expressed support for Ukraine, in some anti-imperialist circles, dialogue is often immobilized when someone associates Ukraine with NATO, Nazis, or nukes. In this interview, Hanna Perekhoda, a Ukrainian socialist and historian, succinctly addresses some of the most controversial among these stumbling blocks. She explains supposed Russian-language oppression and Russophobia is akin to the anti-white racism rhetoric rising in the West. Perekhoda speaks to Putin’s claim that Ukraine is overrun by Nazis, a propagandist justification for the war hearkening back to Second World War mythology. She acknowledges Ukraine’s far right, noting they have repeatedly proven to be a fringe movement. Given that problems with the far right exist everywhere, she questions whether this justifies a full-scale invasion or a withholding of military support or other aid. She notes that what really risks a rise in fascism is a long-standing war waged by a fascist Russian regime where common Ukrainians are radicalized by years of military occupation and systematic oppression. As Perekhoda makes clear, what is needed is support for Ukrainian lives, autonomy, and resistance.

Ordinary People Don’t Carry Machine Guns: Thoughts on War (2025)