Standing in a crowd of a few thousand auto workers, their families, and union and community allies rallying outside General Motors’ Oshawa truck plant in June, I couldn’t help but think, “Way too little. Way too ineffective. Probably way too late.”

In my more pessimistic moments, I wonder if this isn’t true of the situation facing the labour movement as a whole. Canadian labour leaders and activists will need to be proactive and creative in the coming months and years if they hope to avoid the fate of those Oshawa auto workers.

The auto workers’ rally followed a valiant two-week blockade by CAW Local 222 of the automaker’s head office after GM announced the plant would close, putting 2,600 people out of work. Local union leaders speaking at the rally railed against their double-crossing employer, which just two weeks before had inked a new contract that included wage, benefit and other concessions from the CAW on the promise of new investment in the Oshawa plant.

But despite much tough talk and the well-publicized rally, the union was never able to make the blockade anything more than symbolic. A court injunction filed by GM ended it, and the ordeal left the majority of workers frustrated, bitter, and angry – hardly results that anyone in the labour movement could spin as positive.

Lacking the militancy that empowered auto workers in the past, and now with an all-too-often compliant relationship with employers – in addition to far too few organizing gains in an increasingly non-unionized auto sector – the CAW has lost much of its ability to maintain industry wage standards and has forfeited a good deal of its clout with the big three auto employers; Ford, GM, and Chrysler.

What CAW members are learning the hard way is that their recent embrace of concessions, labour-management co-operation, and political lobbying for subsidies and competitive business supports does not add up to a winning approach for working people.

The CAW’s troubles, though, are only symptoms of much bigger problems for organized labour. Throughout North American and Western European labour movements today, unions face an ever-growing list of challenges, from increasing financial globalization and industrial competition, to ever more frequent lay offs in unionized manufacturing, to the expansion of low-wage, non-standard, non-unionized jobs. Unfortunately, the outcome is always the same: organized labour loses the battle. Now, the movement is in serious retreat.

Even if there are small victories – and there are some – unions in Canada and abroad have given up many of their best means for protecting workers. Organizing – the hard work of bringing the benefits of unionization to unrepresented workers – has fallen off the map. Militancy is more often than not spoken of as ancient history. Partnership deals with employers are now regularly sold to members as the only solution. Too often, unions are now using concessions as the default position in their efforts to keep companies from closing workplaces entirely.

As a result, workers perpetually find themselves on the losing end of an economic conflict that sees business reap record profits in boom times while workers feel the pain in times of crisis.

Many things will have to change. But the basic facts are clear: unless unions tack in a different direction and begin making changes to everything – how they organize to the focus of their education programs to how they mobilize politically – rolling defeats like the one in Oshawa will continue to lay the groundwork for even greater losses in the future.

How bad is it?

How bad is it? For unions and working people here in Canada, pretty bad. It’s even worse in countries like the United States and Great Britain. Over the past 30 years, the rise of global finance and the spread of shareholder capitalism into ever larger transnational corporations has forced labour into retreat.

Twenty years ago, business used to finance itself from commercial bank loans. Now with governments reforming financial and corporate governance systems, business has taken the bulk of its financing from bond and stock markets – the new “shareholders” in global capitalism.

The results have been disastrous. Focused on driving down costs and maximizing the flow of profits to stockholders, multinational corporations have sought to put the brakes on labour rights, and to push back any and all gains labour made in the post-war period.

International operations like General Motors have used debt to finance takeovers the world over, and then engaged in massive cost-cutting through shutting plants, laying off workers, and cutting wages, all the while opening more non-union operations in cheaper regions around the globe.

Other multinationals such as Mittal Steel, the world’s largest steelmaker, under pressure to meet market expectations for better profits and burdened with heavy financial obligations because of their thirst for global mergers and acquisitions, have sought to restrict union organizing and strikes in many countries or sought to bypass unions altogether, using lay offs, short-term contracts and outsourcing to maximize profit.

Unions have not been able to put up much of a fight. If weighted for size of the workforce across North America and Western Europe, union coverage of workers has declined from some 33 per cent of the workforce in the early 1980s to less than 21 per cent today.

In the U.S. and the U.K., the numbers are even more abysmal. American unions lost more than nine million members over the past 30 years, with union density slipping to 12.5 per cent overall and a measly 7.4 per cent in the private sector. In the U.K., meanwhile, unions saw their numbers decline by over six million and union density fall by almost half to 29 per cent over the past 25 years. In both countries organizing is at a standstill, with certification of new workers at less than 20 per cent of the number required even for unions to maintain their current numbers.

In Canada, while officially unions do not appear to be in a similar crisis, the situation is far from rosy. The loss of hundreds of thousands of unionized manufacturing jobs, along with manufacturing restructuring, lay offs and outsourcing, has driven private-sector union density over the past few years to Depression-era lows of 15 per cent – less than half of the 34 per cent reached in the early 1970s.

In auto manufacturing, primary metals, forestry, and textiles, plant closures and workforce reductions have ravaged unionized workplaces. In Ontario, the manufacturing sector eliminated 32,000 jobs this past July alone. Since November 2002, a total of 375,000 manufacturing jobs have disappeared, the majority in unionized manufacturing.

If not for organized labour’s public-sector expansion in Ontario, Quebec, Alberta and British Columbia, the prospects for organized labour in Canada would appear even more dismal, as unionized jobs in education, health, and social services jobs accounted for close to 70 per cent of all growth in the unionized workforce over the past decade.

Unsurprisingly, as organized labour has lost ground, working people have seen their economic fortunes decline as well. Today in Canada, 51 per cent of workers are either in non-standard jobs or in low-paid full-time jobs.

The majority of immigrants today earn less than a third of what most white workers make, and most Statistics Canada estimates of “low income” status (i.e. serious poverty and really bad jobs) for recent immigrants exceed 40 per cent. Young workers face similar obstacles. In 2005 in Ontario, for instance, 94 per cent of all jobs for workers between the age of 15 and 24 paid less than $20,000 annually and 90 per cent of jobs for young workers were part-time, temporary, or non-standard.

Schooled by the public sector

What has organized labour in Canada done to stem these reversals? In the public sector, quite a bit. Throughout much of the private sector, not nearly enough.

Selectively using strikes to win and preserve principles essential to their collective agreements, some public-sector unions have galvanized their memberships to engage in widespread public advocacy for better public services, community-sustaining public-sector jobs, and publicly accountable management. In doing so, they have often garnered broad public support.

Last fall, for instance, city workers in Vancouver rejected contracting-out and refused to back down on demands for pay equity. Five thousand CUPE-represented workers went out on strike for three months and avoided major concessions.

Similarly, in 2004, after the Campbell government ripped up collective agreements and contracted out work, the B.C. Hospital Employees’ Union (HEU – a division of CUPE) launched a week-long strike with over 40,000 health care workers. Supported by many other trade unions, they too used a strike to garner wide support and then challenged the Campbell government in court – and recently won. Indeed, nurses across the country have also regularly used strikes, both legal and illegal, to protect jobs, wages, and working conditions.

In the face of these attempts, governments have legislated public-sector unions back to work, frozen wages, forced workers to accept privatization of public infrastructure and public jobs and arbitrarily extended contracts. Provincial governments from Newfoundland to B.C. have also threatened public-sector unions with further draconian actions such as essential service legislation that removes the right to strike and bills like B.C.‘s Bill 29 and Saskatchewan’s Bill 5 that removed the right to unionize for thousands of workers.

Yet the numbers suggest that such public-sector workers have been better able to fight back than have unions in the private sector.

Sticking to a form of unionism that combines militancy with bargaining, and public advocacy with member education and mobilization, public-sector unions have been able to stave off concessions and in many cases make steady gains. Public-sector unions have also continued to work with a host of community groups to advocate against the privatization of services from health care to water, social work to pension financing – something that most private-sector unions are not doing.

Many such public campaigns, as in Hamilton, Edmonton, and Nova Scotia, have even reversed earlier privatizations of water utilities, recreation facilities and schools. Meanwhile, in Montreal on May 3, 50,000 workers came out in protest of planned further privatizations of Quebec health care.

Moreover, this past spring, a recent Supreme Court ruling on the legal challenge launched by the HEU declared that provincial governments do not have the right to exclude workers – like those in health and community social services – from constitutionally protected rights to freedom of association and to form unions, and ordered the provincial government in B.C. to pay $75 million for compensation and retraining.

By holding to traditional tactics like strikes, mobilization and advocacy, a number of public-sector unions have protected and improved wages and working conditions. In health care, long-term care, and nursing, many provincial public-sector unions have gone even further, using coordinated and centralized styles of bargaining to lift all members to the best level possible.

By way of contrast, the gains won by private-sector unions have been smaller. Few have systematically combined organizing, militancy and effective public advocacy in order to win concrete victories.

A good example of effective private-sector union activism has been the United Food and Commercial Workers’ decade-long fight to improve the conditions of foreign agricultural workers, most notably in southern Ontario. Through a court challenge on the constitutional right of farm workers to unionize and the founding of migrant worker support centres as well as provincial advocacy, the UFCW has forced industrial farmers to provide basic necessities like clean water and bathrooms. The union has had some success in making the Canadian, Mexican, and various provincial governments uphold the bare minimum of standards, and has recently launched organizing drives on four farms. Just this past June the first contract for 14 migrant agricultural workers was certified in Manitoba.

But for all the UFCW’s efforts, though, foreign agricultural workers in Ontario still only have the right to “associate” – not unionize – and across Canada, agricultural workers are still exploited with impunity. Many face daily threats of firing and deportation, while working on farms that do not extend even the basic provision of drinkable water and adequate shelter. But major improvements in the situation of migrant farm workers in Canada will require both renewed energy by the UFCW and a strategy of broad coalition building across and beyond the labour movement.

The same is true for the growing thousands of low-paid workers in precarious employment. In Toronto, some of the largest public- and private-sector locals in Toronto have chipped in to support a Workers’ Centre geared to helping and educating workers about their rights at work. Led by one of the toughest, streetwise organizers around – Deena Ladd, a one-time UNITE organizer and long-time community activist – the centre has had some success not only in mobilizing workers to bring bad employers to heel, but also in bringing much-needed media attention to the extent to which low wages and poor working conditions are prevalent throughout the greater Toronto area.

But for the six million plus workers across Canada who are stuck in bad jobs, this is little more than the proverbial drop in the ocean – good intentions to be sure, but hardly strong or effective enough to shift the balance of power in favour of workers.

Retaking the initiative

The facts are pretty plain: within Canadian unions today, there is too little organizing, too few strikes, too many management-partnership deals, and little strategic thinking or member mobilizing.

Despite much talk and countless resolutions over the past decade, the majority of Canadian unions have failed to make organizing a priority. Attempts to organize new workers have fallen by 25 per cent over the past decade. At the same time, new certifications of workers have fallen to record lows of 40,000 per year, down from 100,000 plus in the 1990s.

During the last national survey in 2001, it was discovered that only 6 per cent of Canadian unions spent more than 20 per cent of their revenues each year on organizing new workplaces that lack union representation. Over one-fifth did not spend anything at all, and almost half spent less than five per cent on organizing. If this were not bad enough, approximately half of Canadian unions have no dedicated staff organizers exclusively responsible for organizing, and set no specific organizing targets.

Even more disturbing is the fact that internal numbers at two of the largest unions reveal that fewer than half of new certifications are actually new union members. Rather, these certifications are simply the result of representation votes among competing unions in the wake of sector or employer restructuring or mergers – the labour movement effectively cannibalizing itself – or simply due to internal growth in a bargaining unit within a workplace.

The effective use of strikes to make real gains is also on the wane. In the 1960s and 1970s, union leaders along with rank-and-file militants were hardly afraid of using strikes to spur union growth and win organizing drives. This is no longer the case.

Work stoppages due to strikes and lockouts in Canada fell from an annual average of 754 in the 1980s, to 394 in the 1990s, to 319 in the 2000s. Workdays lost from strikes have fallen from highs of 11 million in the late 1970s to 5.5 million annually in the 1980s, to no more than 2.6 million over the course of the 1990s and early 2000s. Where close to 20 per cent of workers would be involved in at least one strike a year in the mid-1970s, at best no more than one per cent are today.

Such a reversal is part of a larger shift in unions. Leaders and staff have moved from an offensive to defensive posture, focusing less on expanding the frontiers of labour’s power in the workplace and simply trying to defend what has already been won. When doing so appears impossible, unions are then resorting to concessions. Union after union has abandoned the selective use of strikes to make gains or to preserve things once thought essential to collective bargaining, and instead seeks simply to sign agreements with employers, while doing no public advocacy at all.

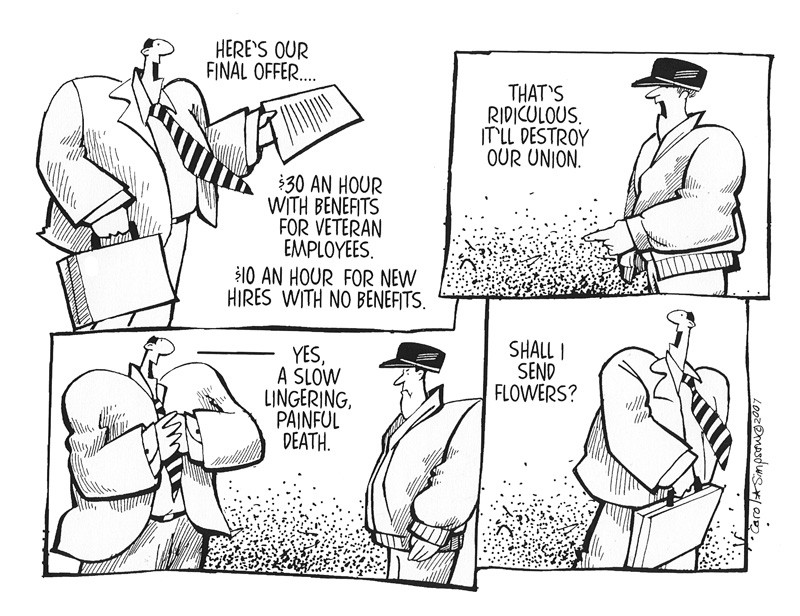

On top of this, some in union leadership are promoting new business-oriented strategies – employer partnerships – ostensibly to bolster declining numbers and to protect jobs. The CAW’s recent joint labour-management agreement is the most well-known of these. The Magna agreement signed away the right to strike and the shop-steward system for the promise of an arbitration system and further organizing in Magna’s plants.

Such agreements are, in fact, increasingly common throughout the private sector. In everything from long-term care to low-end manufacturing and forestry, Canadian unions have signed partnership agreements that impose wage and benefit concessions with the hope of holding onto unionized jobs.

Early results show the risks of this conciliatory approach to be far higher than the rewards. For in adopting partnership strategies, too many union leaders have sold collective agreements to members on the basis that the interests of union and management are the same – when they are not, as manufacturing plant closures like that in Oshawa have emphatically showed.

Wake up? Stand up?

The easy response to all this would be to say that union leaders need to stand up and lead, and workers need to wake up and take action before a century’s worth of victories are swept away.

But things are not so simple. Many leaders are old, as are their memberships, and too few are willing to change direction and take the high-stakes risks necessary to move forward. Too few union staff have the educational opportunities required to learn how to deal effectively with global consulting and law firms that now regularly advise transnationals and governments alike.

Too many unions lack the basic talent to weave bargaining with sophisticated communication strategies and political advocacy. And outside of some labour councils – such as in Toronto and Montreal – there are simply far too few activists in positions of leadership. Within unions, there are even fewer with the gumption to make substantive changes.

Politically, the problems are just as large. Traditionally, unions have tried to influence elections, legislation and policy through backing social democratic and, in Western Europe, socialist parties.

In Canada, unions joined the political left and formed the NDP in 1961 to fight for basic universal rights and equality. Added to this were Quebec unions that formed the Parti Québécois and pushed for public-sector unionism, universal public services and provincial control of finance and industrial development.

But over the past 20 years, union enthusiasm for the NDP and the PQ has given way to frustration and ennui.

Few unions have been happy when the political parties that are supposed to be the “friends of labour” turn to “third way” politics that say little about regulating finance and protecting working people, and have too often led to accommodating business interests at the expense of better wages and jobs.

The majority of unions remain affiliated with the NDP and the PQ. But NDP support for back-to-work legislation and public-sector cutbacks, and PQ support for free trade, has led unions like the CAW to break ranks and turn to strategic voting and issue campaigns in lieu of political support and the political education of members on the importance of parties of the Left.

Today, only roughly a quarter of union households vote for the NDP in federal elections (only slightly better during provincial elections); in Quebec, only a bit better than a third do so. The large majority of workers vote for the Liberals and the Conservatives and in Quebec today, the Action Démocratique du Québec.

If nothing else is clear, an agenda for change is more necessary than ever for the labour movement. But what any agenda for change requires is a template for how to make reforms within unions themselves as well as how to move forward politically.

Putting class and capitalism back into the equation would be one good place for unions to start. More education and social movement mobilizing for global equality and environmentally sustainable politics are two others.

The problems beg for solutions. One can only hope that activists and union leaders will begin to take the necessary steps to go beyond “far too little” and “far too ineffective” before it is, in fact, far too late.

John Peters is a political scientist at Laurentian University in Sudbury, Ontario. He is currently studying the impacts of globalization on labour movements and public policy in North America and Western Europe.

_780_520_90_s_c1.jpg)