Will the largest gathering of activists in years succumb to the left’s culture of complaint, self-victimization, and fracture, or can platforms for renewed organizing and real strategizing emerge from a weekend in Ottawa?

“What matters is the day after, when we will have to return to normal lives. Will there be any changes then? … The only thing I’m afraid of is that we will someday just go home and then we will meet once a year.”

– Slavoj Žižek, at Occupy Wall Street in 2011

The countdown is on until the Peoples’ Social Forum in Ottawa from August 21 to 24. But surprisingly, one of the organizers can hardly wait until the event – a historic gathering of social movements and Indigenous peoples – is over and done with.

“I’m actually looking forward to September!” jokes Michel Lambert, executive director of the organization Alternatives. “I don’t really mean to sound like I want it to be over, but I’m dreaming that it won’t just be an event. We don’t want to organize one more conference. We want to build something – whatever it’s called, an alliance of people – that cannot stop on August 25 when everyone goes home.”

The vision behind the broad gathering of progressives, which is inspired by the World Social Forum (WSF) model, is to bring together the divergent forces of the left in hopes of working toward common goals and strategies. The event will include assemblies on climate change, labour organizing, decolonization, and poverty, to name a few, and a final larger assembly of social movements that will attempt to establish a common platform.

According to the event’s website, organizers hope to not only foster debate but also “stimulate the emergence of concrete actions and the convergence of struggles.” The expectations are ambitious: organizers are hoping for 10,000 participants.

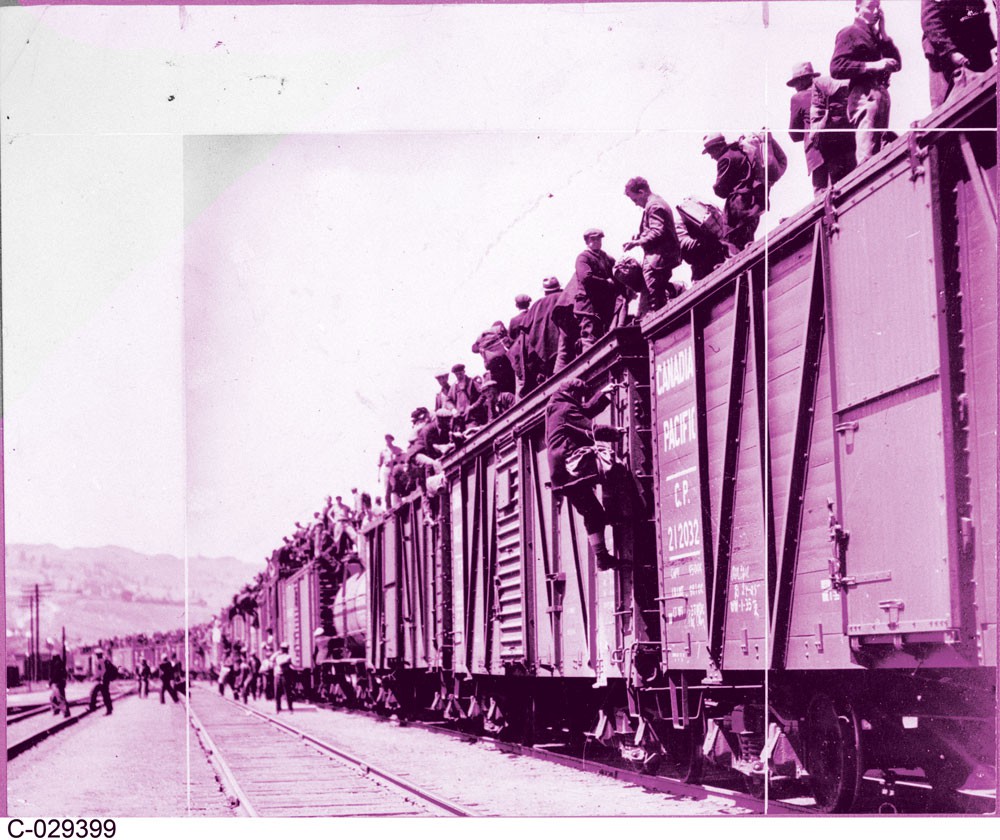

It’s hard to know if that is realistic, but there are dedicated regional organizing committees across the country. In early April, the B.C. committee announced plans to launch a caravan that will gather steam as it travels east. It’s directly inspired, says Vancouver organizer Nadia Santoro, by the 1935 On to Ottawa Trek, where hundreds of men, unemployed due to the Great Depression, jumped freight trains and set off for Parliament Hill (only to be halted in Regina and then attacked by the RCMP in the so-called Regina Riot on July 1, 1935).

“We’re tapping into this history,” Santoro says, “to build momentum and to build the movement for the Peoples’ Social Forum, to raise our voices to Stephen Harper, to say no to the world that he wants, and to present another world … a democratic solution to the crisis that we face.”

While the World Social Forum has centred on people’s movements in the Global South, the heart of the Peoples’ Social Forum in Canada is twofold: social movements and Indigenous peoples.

Gathering at the University of Ottawa, the forum will open with several days devoted to what organizers call “assemblies of social movements” – self-organized workshops on everything from migrant justice to democracy, climate change to spirituality, poverty to the justice system. Rather than big-name keynote speakers or a roster of left-wing celebrities, individuals and groups can suggest and lead themed workshops of their choice. The outcomes of these smaller sessions will feed into the larger thematic assembly, which will in turn feed into the final assembly on social movements.

Many nations

Widia Larivière, youth coordinator with Québec Native Women and an Idle No More organizer, has been involved since the early planning stages. She says that ever since the Indigenous resurgence of Idle No More drew the support of Quebec’s student and Occupy movements, she’s been inspired to bridge the divide that still exists between Indigenous and settler activists.

“When I started getting involved in Idle No More, people who were involved in the Maple Spring and the Occupy movement in Montreal offered their help and solidarity to us,” Larivière says. “It was a special moment; I started getting hope again. I started thinking, ‘How can we make our fights converge, Indigenous and non-Indigenous, all the different groups fighting for social justice and to protect the environment?’”

But because ongoing “colonial attitudes” towards Indigenous peoples persist in parts of the left in Canada and Quebec, Larivière was initially cautious about getting involved.

“I’m always a bit worried at the beginning,” she admits. “I wanted to make sure I knew what the approach is. How can we start decolonizing our relationships, mentalities, and the way we make partnerships – and collaborate?”

What reassured her, in the end, was feeling included in the whole planning process, not simply tokenized or brought in at the last moment. She is part of the forum’s Indigenous caucus, one of several sectoral clusters within the larger event.

“They wanted to make sure Indigenous peoples would be part of the process as equals,” she says. “That’s why I got involved.”

The Harper trigger

Another key sector involved in planning the forum is organized labour, which also has its own caucus. Véronique Brouillette, of the Quebec House of Labour (Centrale des syndicats du Québec), says the Peoples’ Social Forum is a “historic event.” It couldn’t come at a more urgent time, she says, given the Conservative regime in Ottawa.

“It’s time we have an event that permits us to build bridges between the social movements, unions, environmentalists, First Nations, and everyone who’s being attacked by the Harper government,” says Brouillette. “We’re all being isolated with very bad austerity measures. We’re so busy fighting back against all the attacks; it’s easy to be alone.”

But is the focus of the forum limited to a “Stop Harper” message?

“Of course the Harper government is a trigger for action,” she says, “but yes, it’s also bigger than that. We need to think of a better left than we have now. We need a proposal for an alternative way of doing politics, economics, and [relating to]nature. For me, the social forum is just a first step of a series of steps we hope will take place afterwards.”

Organizers say that’s why the forum is being framed as an “extra-parliamentary alliance” rather than along partisan lines. It’s just that Harper has raised the temperature dramatically for everyone.

“We need to build alliances that will go way beyond 2015,” Lambert argues. “We’ve seen that the lines between political parties are not so big anymore. A new one will come in, they’ll repaint the airplane red, but the policies seem more or less the same. We want to build something that can go beyond partisan lines and brings the social movements into an extra-parliamentary opposition – something bigger, that’s my dream.”

Lambert describes such an opposition alliance as a “fourth line” or “citizen’s line.” The level of austerity measures – from cuts affecting postal workers to draconian environmental changes and attacks on Indigenous sovereignty – is simply too dramatic to fight one by one, he says. “It gives everybody a sense of urgency.”

Did someone say strategy?

For one labour movement veteran who attended the World Social Forum in Tunisia, talk about building “something better” is tempered by “systemic” patterns on the left that have in the past hobbled attempts to talk strategy. It becomes difficult to establish “where we’re going and how we get there,” argues Dave Bleakney of the Canadian Union of Postal Workers.

He says previous social forums have left audiences “deflated,” with panel after panel offering a litany of “complaints for the converted” on a patchwork of issues.

Bleakney applauds the energy and passion being poured into the August event, as well as the support from the labour movement, a group that he says took “a long time to come around” to the idea. He sits on the forum’s steering committee but emphasizes that he speaks only for himself.

“It’s magnificent that so many people come together, want change, and are struggling to make that change,” he says. “But I feel a deep dissatisfaction after each [forum] – a kind of let down.”

The left, he says, is good at analyzing the negative impacts of capitalism, corporations, and government policy. But Bleakney says actual strategy is “our Achilles heel, something we don’t do well. It’s easy to find a villain, but that absolves us and lets us off the hook.

“If we want a successful social forum, we’re going to have to break the systems we’ve imposed on ourselves and stop looking to blame someone else.”

The forum’s coordinator, Roger Rashi, agrees that the goal of the event needs to be bigger than stopping a policy or electing a new government. He wants to see a tangible path forward emerge from the forum. At the same time, he insists the current Conservative administration is a unique catalyst for social mobilization.

“Having Stephen Harper in power in Ottawa makes a huge difference,” he says. “His ability to isolate movements and crush them has been so [effective] that we all realized we cannot go up, one by one, against Stephen Harper and win. That’s what drives today’s forum.”

Changing the agenda

Optimism can be tempered by history. The Peoples’ Social Forum comes a decade after a previous, failed attempt at such an event. The earlier incarnation, on the heels of the explosion of the anti-globalization movement, never materialized, partly because of chasms between English- and French-speaking unions and social movements, says Lambert, who was involved in the 2002-2004 attempt.

Although Quebec has since hosted two social forums, the last time French- and English-speaking movements came together from across the country was for the 2001 People’s Summit which confronted the Summit of the Americas free trade talks in Quebec City.

There are many theories about why the anti-globalization movement itself faded from its promising mass mobilizations between 1999 and 2001. Some credit the terrorist attacks of September 11 with demoralizing the left, or at least refocusing it on (unsuccessfully) stopping the invasions of Iraq and Afghanistan.

Others blame a kind of protest fatigue that arose from two years of rapid-fire “summit hopping.” Travelling across the country is time consuming and can detract from local struggles and the patient work of incremental organizing.

Is there a risk that the Peoples’ Social Forum could become just another vehicle for leftist tirades without building real oppositional social power? Organizers insist the plan is to emerge with concrete strategies or at least clear positions on common struggles, to be hammered out in the final larger assembly. But questions remain for some about whether it will become another gabfest.

“Social forums should not just [be] empty talk,” Rashi argues. “We’re looking to build a different world. It’s ambitious – we’re not saying we can do it on every issue or theme – but that’s the approach. If we’re able to bring in all these various struggles and battles popping up into a common fight back, I think we can change the political agenda in this country.”

For Larivière, the challenges of organizing across diversity and difference will hopefully add to the celebratory and strategy-focused nature of the event and not hinder it.

“There’s always going to be challenges,” she says. “We have different visions, cultures, and realities. We have to deal with a lot of challenges. It’s not always easy. But if we want to work together, we have no choice but to face them. I know it won’t solve all our issues, but it could, hopefully, be an important step.”

To learn more about the Peoples’ Social Forum or to register visit peoplessocialforum.org

_780_520_90_s_c1.jpg)