It was early November 2016 when Russell Diabo received a phone call from an APTN reporter, who told him that his was the only name that hadn’t been redacted from a recently released RCMP intelligence document. The document, outlining Project SITKA – a police operation tracking Indigenous activists “who pose a threat to the maintenance of peace and order” – was acquired through an Access to Information request filed by Carleton University researcher Jeffrey Monaghan. It revealed that the police were following 89 activists who met “the criteria for criminality associated to public order events.”

Project SITKA tracks activists organizing around natural resource development (fighting oil pipelines and shale gas expansion), anti-capitalism (G20 and Occupy activists), the missing and murdered Indigenous women inquiry, Idle No More, and land claims. The report concludes that the protesters “pose a criminal threat to Aboriginal public order events,” though it concedes that “there is no known evidence that these individuals pose a direct threat to critical infrastructure.” This proof of surveillance sent a chill through the activist community.

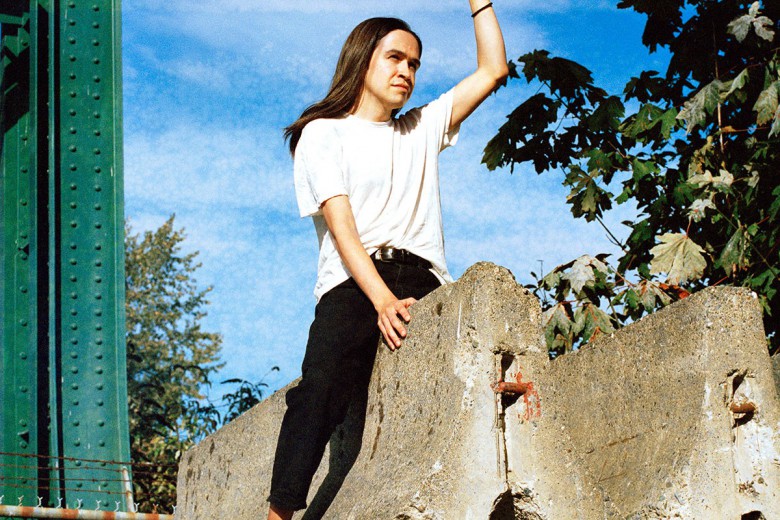

Although Diabo – member of the Kahnawà:ke Mohawk Nation, activist, and policy analyst – is likely not one of the 89 activists under RCMP surveillance, he is named in the RCMP document as a representative of Defenders of the Land, an organization founded in 2008 that mobilizes around Indigenous sovereignty. The organization and several other advocacy groups “are identified within the report, yet are not a part of the analysis,” the report reads, suggesting that Defenders of the Land is on the RCMP’s radar despite its lack of criminality.

This was a disturbing revelation for Diabo, who told Briarpatch, “I found it interesting that in that document I was the only name that wasn’t redacted. Everybody else was redacted. I do say [in a statement that the RCMP flags in the report] that Canada has a war with First Nations … [a]nd the government – well, certainly the RCMP – think[s] my ideas are a threat.”

“Now, I can understand that for some security reasons they would argue that, yes, they have to do this, but I think that they’re going pretty far beyond what they need to do. And without oversight, I wouldn’t trust the police or security agencies in Canada to be fair in how they are policing the country. Or even assessing people who haven’t even done anything.”

Diabo is not the only activist affected by invasive surveillance programs. Blockades against pipeline construction on Indigenous land, and acts of civil disobedience to resist colonial expansion invariably involve the Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS) and the RCMP watching and recording.

Domestic security threats

The Project SITKA report is emblematic of a larger issue in national security intelligence and policing: the emphasis on prioritizing “critical infrastructure.” In the years since the 9/11 terrorist attacks in the U.S., national security in North America has changed shape to respond to a new level of global threats. It has been reinvigorated and prioritized in ways that haven’t been seen since the end of the Cold War.

“Immediately after 9/11, there was a bureaucratic reordering that happened around public safety, homeland safety, [and] public preparedness. All kinds of money flooded into these bureaucracies, mostly rationalized, like Bill C-51, around the Taliban, al-Qaeda, [and] Osama bin Laden,” explains Monaghan, a criminologist at Carleton University.

The elevation of public safety as a national security concern led to the development of intelligence coalitions and fusion centres that focused on the cooperation of government agencies, including the RCMP, CSIS, and municipal police forces.

Over the past 10 years, “critical infrastructure” has emerged as one of the central priorities of national security policing as the government began to fear terror attacks against economic projects. It is a broad and ambiguous legal term that includes almost any infrastructural project in Canada, and it is frequently invoked to shield private industry. For instance, shortly after the Kinder Morgan Trans Mountain and Enbridge Line 3 pipelines were approved by the Trudeau government in late 2016, Natural Resources Minister Jim Carr assured his audience of business leaders in Alberta, “If people choose for their own reasons not to be peaceful, then the government of Canada, through its defence forces, through its police forces, will ensure that people will be kept safe.” His announcement signalled that the policing and intelligence agencies in Canada, empowered by the legislative arm, would go after protesters in order to protect the interests of the energy sector.

“It’s essentially made the police a kind of proxy security company for these industries who want pipelines to keep going into the ground and railways to stay open. When social movements like Idle No More disrupt private industry, they make all kinds of noise … for the RCMP to intervene and stop these protests,” says Monaghan.

This close relationship between the energy industry and the RCMP was cemented in the 2015 Anti-terrorism Act, more popularly known as Bill C-51. The omnibus bill was introduced by the Harper government following the shooting of a military guard at the National War Memorial near Parliament Hill. C-51 aimed to overhaul Canadian national security law by granting CSIS expansive new powers, refocusing concerns toward “critical infrastructure,” introducing invasive surveillance data sharing, and curtailing free speech rights surrounding “terrorism,” among many other changes.

Though Bill C-51 was justified as a response to the threat of terrorism, like previous changes in the national security apparatus, it is also a tool of social control against activists. As Micheal Vonn, policy director of the British Columbia Civil Liberties Association (BCCLA), explains, C-51 “imports a completely new definition of what constitutes a national security concern in Canada. The act recasts the threshold of concern to something that ‘undermines’ the security of Canada, not threatens it.”

This reconfiguration of threat thresholds forges protest as a danger to public order, casting it as a national security concern. The government insisted that the act would avoid targeting “lawful” dissent and protest. But SITKA is evidence to the contrary. It demonstrates that national security surveillance is used to explicitly target those who are critical of the settler state, which has major implications for the imperative, and right, to dissent.

Consult and distract

From September to December 2016, the federal Liberal government held an online public consultation on amending C-51. With the launch of the consultation, the government published a backgrounder called the National Security Green Paper. The document positioned the government’s goals as balancing security and privacy concerns to address “problematic” elements of the legislation. But the backgrounder itself revealed the government’s partiality. As Privacy Commissioner Daniel Therrien warned, “It focuses heavily on challenges for law enforcement and national security agencies, which doesn’t present the full picture. Canadians should also hear about the impact of certain surveillance measures on democratic rights and privacy. A more balanced and comprehensive national discussion is needed.”

While the consultation process was framed as addressing the act’s unaccountability, CSIS’s expanded powers, and implications for charter rights, the green paper read more like a sales pitch that sought to convince the public of the need for increased surveillance. In the area of digital technology, for instance, the green paper deliberately framed the stakes: digital technology “can also be exploited by terrorists and other criminals to coordinate, finance and carry out their attacks or criminal activities,” it read. Empirically, this is true, but the framing functions to ensure that there is no sensible option but to encourage public consent to surveillance in its current iteration. Where the green paper discussed activists, it asserted that Bill C-51 does “not include activities of protest, advocacy, dissent or artistic expression,” despite the fact that surveillance of activists regularly occurs.

The issue of critical infrastructure was not up for discussion in the consultation, signalling the government’s entrenched protection of resource extraction concerns. Diabo argues, “That’s why I think Bill C-51 … [is] the real threat, because that defines [Indigenous] activities as being threats to Canada’s sovereignty, security, or territorial integrity. And by being born Indigenous peoples, we have to challenge Canada’s security, sovereignty, and territorial integrity.”

Even in the unlikely event that the consultation process results in policy that curbs surveillance, policing of critical infrastructure will likely remain unchanged, creating major implications for the work of anti-colonial activists. Given the deep-seated history of colonial expansion and violence in Canada, national security policing will disproportionately affect Indigenous protesters who protect the land through direct action. This has been the case with protests in Elsipogtog, and it will likely be the case in future resistance to the Kinder Morgan pipeline.

Racializing surveillance

Simone Browne, a surveillance studies scholar at the University of Texas at Austin, has examined the effects of surveillance on people of colour and Indigenous people. Racializing surveillance is a particular layer of surveillance that reinforces notions of race and racial stereotypes, and determines who should be considered suspicious. Surveillance, in this sense, “does the work of arranging race within society,” she says. The arrangement is almost always problematic.

“Settler countries rely on this national colonial fantasy of terra nullius. The idea of situating people who were brought here forcibly, as in slave labourers, or people who were subjected to colonization and genocide, as ‘not belonging,’ as others, as unfixed … [t]hat narrative has not changed,” Browne explains.

Surveillance practices, such as those highlighted in the Project SITKA document, become markers for racializing and criminalizing Indigenous peoples. “Anyone who is challenging the state or any types of legislative or policing acts becomes seen as suspect prior to … doing anything that might be suspicious,” says Browne.

To question the legitimacy of a settler-capitalist state in those terms provokes a response that construes dissent as a national security concern. “Movements that declare their own self-determination and demand nation-to-nation status and reject the notion of Canadian sovereignty – they’re all seen [by the state] as belligerent, which increases their levels of threat,” Monaghan asserts.

Diabo’s politics brought him under the scrutiny of national security agencies like the RCMP and CSIS. His critical analysis of the sovereign authority of the Canadian state appears to mark him as a threat to the established order. Other Indigenous activists are flagged for meeting the RCMP’s criteria for serious criminality, and they remain flagged for public-order surveillance. The gaze of national security spies doesn’t flinch.

Repeal and rebuild

As Vonn points out, Canadian security agencies operate in a culture of impunity that normalizes and facilitates law breaking under the excuse of “noble illegality.” In other words, they are able to justify their careless treatment of the law by declaring it in the public interest. Between the discourse and culture normalizing noble illegality and anemic legislative oversight, Bill C-51 becomes especially dangerous, allowing the state to routinely ignore the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms; C-51 empowers judges to authorize charter infringements in secret hearings when CSIS deems it necessary to “take measures” against suspected threats. When the construct of threat reflects settler-capitalist logic, the entire process becomes dangerous for those who dissent.

In 2017, as the state cheerfully promotes its official celebrations of Canada 150, communities are strengthening calls to end pipeline expansions, the state’s co-optation of reconciliation, and all violence against land and Indigenous women and two-spirited people. The revelations of Project SITKA are chilling, but they should also provoke vigorous organizing against surveillance itself. Surveillance cannot be treated by organizers as an ancillary issue, or as a routine cost of organizing. With the deregulation of surveillance and policing, we can expect that abusive practices will threaten the very potential to resist in meaningful, foundational ways. As Vonn warns, “It is very, very hard to turn something around once it has already been installed.” This means we must organize now, or risk losing the right to freely organize at all.