Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside (DTES) has long been known as the poorest off-reserve urban neighbourhood in the country. That may still be the case, but the invading forces of gentrification are relentlessly occupying it, with ominous consequences for the predominantly low-income residents.

The speedball of gentrification was Woodward’s. This massive historic department store was a site of contestation since it closed its doors in 1993. The community fought against various plans for upscale development to preserve it as a space for low-income residents, with social housing, affordable food, accessible services, and other amenities. This struggle culminated in Woodsquat, the occupation and tent city that lasted three months in the fall of 2002. Eventually, the City of Vancouver collaborated with developers, retail businesses, an educational institution, and non-profit housing providers to produce a model of “social mix” that would showcase its vision for the area and set the course for future development.

In the run-up to the 2010 Olympic Games, Woodward’s unleashed 536 condo units into the DTES, along with large retail outlets and other businesses, and a satellite university campus (Simon Fraser University’s Goldcorp Centre for the Arts). Since then, a number of new condo projects have emerged within blocks of Woodward’s, and over 1,000 market units have been built or are scheduled for construction throughout the DTES. In the shadow of Woodward’s two towers, housing once available to low-income residents has been transformed into condos and high-priced micro-lofts or lost through rent increases.

A desk clerk at the Metropole Hotel across the street from Woodward’s succinctly expressed the impact of it when he told a researcher from the Carnegie Community Action Project, “We’re trying to get rid of the welfare people.” As the activists fighting to save Woodward’s for the community knew all along, as Woodward’s goes, so goes the neighbourhood. The floodgates of gentrification have been blown wide open by the Woodward’s “experiment” in social mix and revitalization.

In addition to market housing, dozens of new retail businesses now occupy the storefronts along the main arteries of the DTES, offering consumers an array of fine dining experiences, pricey microbrewery beer, expensive furniture, fake suntans, new fashion, and $3 doughnuts. This material transformation of the streetscape is accompanied by a noticeable cultural shift as well. As increasing numbers of wealthy urbanites come into the area to shop or dine, the “frontier” of the DTES becomes a more comfortable and familiar space, and the newcomers’ privilege and entitlement quickly dominate the social terrain. The growing presence of hipsters in the DTES changes what was once known as skid row into the “new community of cool,” with the accompanying disregard or disdain for local residents unable to assimilate to the emerging ethos.

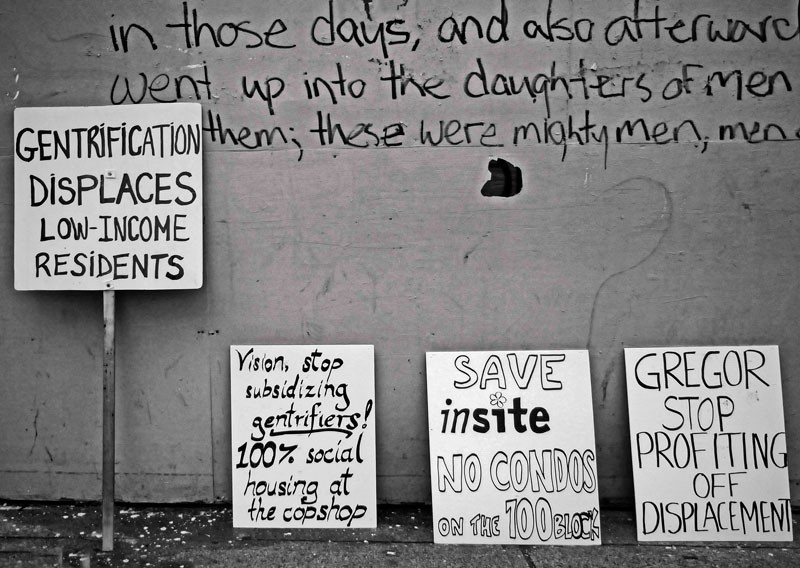

In the game of urban transformation, political decision-makers at city hall are key players. With their scripted policy of social mix chiselled in stone, they manipulate the levers of change by deploying various mechanisms of zoning, permits, and licensing to promote upscale development on the ground.

Vision Vancouver, despite its brand image as a progressive municipal party, has up-zoned Chinatown to pave the way for a flood of condo towers and has approved a massive project of 282 market housing units and 70,000 square feet of retail and light industrial space on the eastern edge of the DTES (dubbed “Woodward’s East” by local residents), all in the face of significant opposition by the low-income community. Not surprisingly, this is the project of Vancouver developer Wall Financial, which has close ties to Vision Vancouver and has contributed, through its subsidiaries, over $200,000 to the party’s coffers.

Although Vision Vancouver has implemented a Local Area Planning Process (LAPP) and engaged some low-income residents within that strategy of community consultation, they have, in the midst of the process, given the green light to hundreds of condo units and numerous businesses, including “Woodward’s East.” Herb Varley, a young Indigenous resident and activist in the DTES and co-chair of the LAPP committee, poignantly expressed his own frustration with the process: “After two years of working with the City I wonder what we have been included in. It feels like the only questions we get to answer are about how we would like to die, slow or fast, not whether we want to live.” As the LAPP winds down and the city prepares its final report, the low-income members of the committee have issued a call for a social justice zone in the DTES that would prioritize the needs of low-income residents for housing, adequate income, non-discriminatory services, and improved safety.

The city’s policy of rampant gentrification and the discursive logic that accompanies it are amplified and disseminated by the mainstream media. Last February the sustained anti-gentrification protests outside the posh PiDGiN restaurant provoked a spate of media coverage, the vast majority of which voiced full support for the restaurant owner and disdain for those who opposed efforts to “clean up” the neighbourhood. Historically, the mainstream media have played an important role in popularizing the dominant poor-bashing, stigmatizing perspectives of the neighbourhood while applauding the courage of “socially conscious” entrepreneurs and consumers in bringing positive change to the “blight” of the DTES.

As real estate developers, retail business owners, municipal politicians, city planners, and media pundits promote the gentrification agenda and shape public policy and perception accordingly, police and private security ensure that those whose lives are most disrupted and harmed by these massive changes do not disturb the new inhabitants and their economic and social investments. The DTES is the only district in the city with its own specialized (and filmed-for-reality-TV) Beat Enforcement Team; here, police presence is relentless, and surveillance, harassment, and ticketing are epidemic.

The Vancouver Area Network of Drug Users has frequently voiced concern about the ways the area is being “mined for crime,” and recent data has revealed that in the past four years, 95 per cent of the city’s bylaw tickets for street disorder violations – including jaywalking, vending, spitting, and urinating in public – have been issued in the DTES. In addition, business improvement associations hire private security companies to harass panhandlers and sex workers in order to maintain an atmosphere that ensures comfort for condo owners, business operators, and their patrons.

Of course the fallout of gentrification on low-income DTES residents is devastating. Upscale real estate development drives up property values and produces a domino effect of increasing rents and renovictions. The end result is involuntary displacement and homelessness. For those who struggle to pay escalating rents, financial strains translate into mental and physical stress, and personal health deteriorates. The rapid emergence of retail businesses proliferates zones of exclusion that are inaccessible and unwelcoming to residents on limited income and exacerbates the experience of alienation and dislocation within one’s own neighbourhood. Necessary strategies of survival entangle low-income people in the criminal justice system, or they are coerced into carefully managed regimes of medical and therapeutic support that operate as systems of social control.

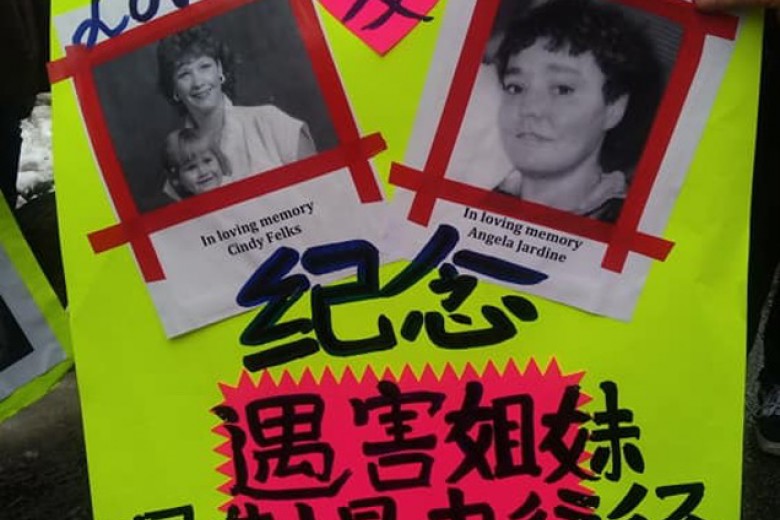

As gentrification transforms physical space and social relations to further elite interests, life-giving networks of care and support that low-income residents have developed and relied upon for years are threatened or disrupted, and displacement from the neighbourhood produces greater isolation and impending violence. A community that has been characterized by remarkable acceptance morphs into a place where non-conformity to the status quo is made more visible and deviance elicits increased efforts at management or removal. Demarcations between “good” and “bad” poor are heightened and manipulated by organizations, service providers, and dominant media to serve their own ends.

All of these pressures of transformation produce increasing conflict at many levels: between the new condo owners and wealthier consumers and the low-income residents, between those who can navigate the social changes well and those who feel alienated and desperate because of them, between those engaged in daily survival and the managers and enforcers of civil order.

Fundamentally, gentrification in the DTES replicates the dynamics of colonization. It’s a strategy of accumulation by dispossession that is rationalized by paternalistic notions of benevolence (“we’re improving the neighbourhood”), normalized by hegemonic, state-supported market logic (“it’s the natural evolution of progress and healthy change”), and reinforced through ideologies of gender, race, and class hierarchies (“we [mostly white wealthy men] know best”). Like colonization, gentrification is a process of immense violence inflicted on the bodies, minds, and spirits of those who are deemed in the way of political and economic power.

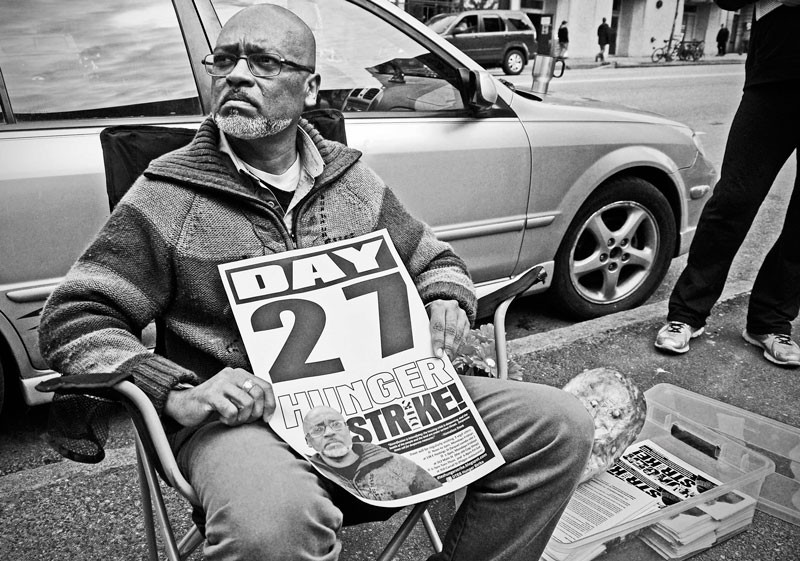

But the DTES low-income community is remarkably resilient and strong. It is rooted in a history of collective struggles for social justice. It’s a community that has engaged in confrontation, agitation, and determined resistance against the forces that have threatened its vitality. It knows that capitulating to the gentrification agenda will only result in more humiliating charity, more bureaucratic regulations, more social control, more displacement, and more homelessness, and it says, no!

This spirit of resistance is also accompanied by clarity of vision. The refusal to be dominated by elite political and economic interests is fuelled by a vision for the neighbourhood grounded in the lived experience and collective wisdom of the low-income community. It is a vision of social justice, mutual care, and human dignity; it’s an inextinguishable affirmation of life and freedom. The DTES is the heart of the city, and it will continue to beat strong despite the pressures of gentrification brought against it.