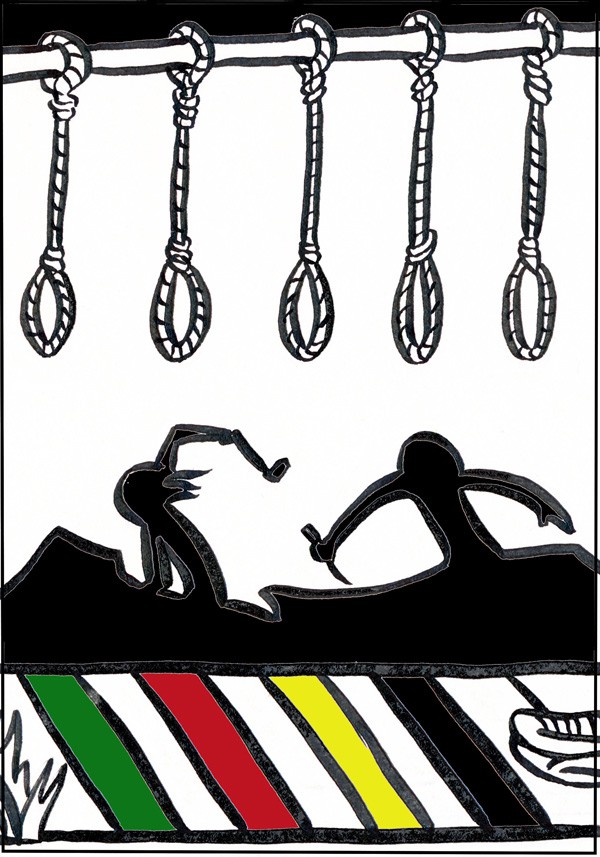

Two worlds overlap, drifting sullenly between clouds and shadows. Only one body desires to consume itself in darkness overnight. Suited as predatory capitalists on a mission, manifest destiny manages to migrate across fictitious borders on its way to harvest flesh. War for “Whites” means humiliation to satisfy power through the rigours of sacrificial violence. Men aiding the men of property unshackle my ancestral relatives and lead them to a wooden structure. With the river’s strength flowing behind them, the water scripts its forever return downstream only to come back. That day in 1864, among a modest crowd drawn into the spectacle, five honest men hang.

***

The courtroom is a place of doubt. It is sterile and hosts normal temperature to give it the godly touch of neutrality. It appears the carpeted floors are kept relatively clean for the dirt that enters. The symbols of the Crown lay hanging: the Queen and country flag form the background. While the floor is seething red, the stained wooden tables divide the judge’s seat from everyone else. Black robes encompass formality, and their objectivity shows no sign of emotion. In the air, the audience nervously sits in cold silence. In the air, the reporters tick their scroll with ink, echoing words in print that act as blunt and crooked weapons. Deflecting and breaking truth is the substitute for mass violence. The damage has been done. It’s time to clean up. Someone calls this place Justice. Even in modern times – where media coins currency as message – time calls us back to the source.

***

Paradoxically, you think much has changed, and nothing has. Lingering trauma, death, being a part of life, changes things.

***

A large boat is anchored off the shore, a fair distance from port. The muddy scum from the shipmates’ boots rubs against the deck. The air is crisp. Every passing breath leaves tracks in the wind. The tobacco withers below rolling clouds. The morning is chill, more than enough to keep the living awake. Back against the ocean’s elements, every person on the coast is dying in agony, bursting in pockmarks and shrill tears.

All the while, the doctor, in good health, waits. He witnesses the last sorrows, and dying embers wither as if purgatory sits patiently along the beach. The timing is scientific, estimated. It has proven to work over and over again with repeatable success. He begins to pace back and forth in the sand, knowing he has a task ahead of him. Never turn back for too long. Committed, these men hastily hold the stench, while peeling the scabbed skin into containers ready for export.

***

Peering at an imaginary piece of history, a newly crafted painting titled Justice is permanently embedded in the B.C. legislature. An Indian man waits in a makeshift Quesnel courtroom, held in front of colonial officials like a little child, for justice to be done. The rules change, of course, when an Indian awaits trial. The legislature, where this picture hangs, represents the colony, which entered someone else’s country and mandated a foreign law to supersede the original peoples’ laws. Embarrassed by the potentially offensive mythological propaganda the mural displays, the colony first fails in its attempt to remove it and then decides to cover it up. Such a fitting response by colonizers: hiding their mistakes and then layering past history with story after story.

His story is elusive. She has her story mediated; it diverges into opposite directions. While one group of women arrives in Victoria by boat to be claimed by men, another group of women, gatekeepers and matriarchs, becomes a target of attack. His story is split between two wives, though he loves one more. Before his death, William Manning’s wife waits in Victoria with their two children, unaware of his activities. Meanwhile, he uses a Tsilhqot’in woman to gain access to Bendziny, an HBC custom of legitimate infiltration. He quickly builds a roadhouse, fences the pre-empted property occupied by a large Tsilhqot’in village, secures access to shared communal water, then aids the McDonald clan in armed robbery.

***

The medium of choice is the smallpox weapon: strong medicine, they say. Plagues sweep the land with carriers of guns, religion following closely at hand. Weapons wielded by conquerors assume there is no talking back, especially to the dead. Purging fear is easy when done with calculated violence. Known for his brawling manner and drunken fits, Ranald MacDonald travels extensively and becomes carrier of the weapon. Perhaps, you may say, the medium comes from somewhere else, from imported disease, religion, guns, and language. A philosophy of knowing thyself, the purifying kills the Indian in you. You, complicated soul, seek strong medicine. Some see the skin as mixed-blood and call you Métis after all.

***

On Indian land, bronze statues assume permanence. The poles carved of cedar stand tall but return to the earth like every person. In honour of past spirits, they watch over us. The colony’s capitol names its streets in honour of Indian killers: Douglas, Begbie, Tolmie, Helmcken. The killers watch over us, their presence emboldened by their permanence, like the horror it came from. You haunt us in the living; our living haunts you. The statue stands as long as the regime remains. The regime remains and so must the shadowy story of lies and fear.

***

Doubt. Empire writes right. Empire state building escalates, constructing zones, securing walls, to divide people into camps. The logic of Empire becomes a “conform or die” class system that takes other people’s land. Wealth is private. Poverty is created. The unrecognized names of the land erase original nations just by sketching a map: Tsilhqot’in, Nuu-chah-nulth, Stl’atl’imc, Nlaka’pamux, Secwepemc, Ktunaxa, Haisla, Haida, Nuxalk, Heiltsuk, Dakelh, Dunne-za, Gitxsan, Nisga’a, Tsimshian, Kwakwaka’wakw, Syilx, Tahltan, Tlingit. Drawn in ink, everywhere the disappearance commences. Do you still believe that imperial takeover is innocent?

Would you believe that Governor James Douglas, of mixed blood they say, was so devoted to the Empire’s expanse that he helped orchestrate a plan of genocide while at the same time pre-empting occupied land? A loyal Hudson’s Bay Company employee, fully aware of British policy to obtain the extinguishment of land title through treaties, he supports his friends in carrying out the cheapest means possible for a bankrupt colony. Douglas, in competition with New Westminster, positioned to evade America’s northern migration, abandoned by his superiors in London, executes a plan to solve the headache of purchasing land from an Indian majority. Or assume – like every other colonist whose purpose was to cultivate other people’s land – that we admire the will of men whose desire is to, at best, establish reserves for future submission.

***

My family says our ancestors killed Samandlin, Donald McLean, to end the war. Leaving from Hat Creek Ranch, the Scot’s last days are spent heading a heavily armed militia into the Tsilhqot’in. A Hudson’s Bay Company employee, fully aware of British policy to obtain the extinguishment of land title through treaties, he seeks violent punishment as his means of dispute resolution. If you want to talk, then blood will be spilt. Knowingly, there was no need for talking. The Tsilhqot’in leave shavings from trees strewn along the ground as bait. Samandlin, aggressive and arrogant, bearing armour that once saved his life, catches a bullet through his cold heart. He dies miles upstream from where he once abandoned his Native wife and children.

***

Alexis is the Tsilhqot’in mediator who enters the scene soon after Samandlin is put to rest. Leading a group of horsemen, he times his arrival with that of the colony’s newly appointed governor, Frederick Seymour. Alexis and company hold their guns high overhead and dismount to acquaint themselves with the Chief, welcoming the crowd with a song to grant respect for the official occasion. Alexis speaks French, learned from his time interacting with the Métis traders, and wears a dark blue French suit. Translations required: the first nation-to-nation meeting is a curiosity of tense, conflicted feelings, though an understanding is forged. The tobacco offered to the Tsilhqot’in days before by the commissioner bears with it an atmosphere of safety and mutuality and, with it, the hope to amend peaceful relations. Afterward, Seymour requests and is granted safe passage from the territory. The war leaders are brought forward as a gamble to broker peace. Not long after, a handful of Tsilhqot’in are chained and led by horses to Quesnel for trial.

***

The trial, which ends in hangings, is a sham spectacle to enforce brute retaliation and terror. Shedding light towards the shadows of secrecy reveals this conclusion.

Lights, please! The public is shut out, the courtroom is closed to media. Commissioner Cox, assistant gold commissioner and temporary militia leader, bars the doors. Matthew Begbie is the judge, appointed by Sir Hugh McCalmont Cairns to take care of Indians and Irishmen. As soon as he arrives in Quesnel, he invests in property. Begbie’s regular clerk is Arthur Bushby, who is, coincident-ally, the land registrar. As Douglas’ son-in-law, he avoids the trial to evade disclosing insider information. Similarly, potential witnesses to the warring events – John Ogilvy, Frederick Whymper, Francis Poole, and Chief Inspector Brew, among many others – disappear during the trial.

The legal counsel representing the Tsilhqot’in defendants happens to be the brother-in-law to Alex McDonald, the man killed by these same defendants. George Barnston, Begbie’s acquaintance and the colony’s first lawyer admitted to the bar, is also a legal and business partner to Ranald McDonald, the man who happened to precede the parallel route of smallpox and land pre-emption.

A trial conducted by acquaintances and partners in crime. Every move is a conflict of interest. Justice, if you dare call it that, in the colony begins as an elaborate symbolic hoax. Opened wounds of war remain.

***

War, for Tsilhqot’in, is a commitment to persevere, accompanied always by the need for peaceful relations. A survivor writes in his testimonial that the Tsilhqot’in were enjoying the night singing and dancing just beyond their camp. So little did he know. His time at Bute Inlet was coming to an end. Having witnessed threats of smallpox, rape, and all-round disrespect, the Tsilhqot’in were timely in preparing for war. The song and dance is a ceremonial commitment to fulfil a duty. Once you begin, you cannot stop. As the sun bursts on the horizon, the Tsilhqot’in descend upon the road builders’ camp. The aftermath at Bute Inlet leaves fourteen dead. Three survivors retreat to Victoria. The Tsilhqot’in always leave one alive to tell the story. By deleting smallpox, his colonial story gets it wrong.

***

Tell the truth. The choice: if, by chance, people build a society based on lies and deceit, then we must decide whether we will choose the path of truth and justice together. The ultimatum: your prison is built on genocide. Its ultimate wreckage destroys healthy, communal life, scarred by the insistence of the colonial divide, torn by negation of the human spirit. What are you going to do about it?

Tell the truth.

On separate occasions, Raven recognizes that someone guards light and fire. The keeper’s protection chooses not to share. Like colonial times, the men of property have chosen to secretly covet the wealth and maintain the language of deceit buried in myth. But Raven takes every measure to get inside the walls of the keeper’s house, once as needle-born child and once as a pitch headdress dancer flying with the fire. Today, the sacred symbol that yearns to be set free is truth, hollowed consistently by the unreality of white supremacy. Colonial sickness is epidemic in the legislature, in the courtroom, secured in public spaces by erected statues, whitewashed maps carved on women, marked by stretched children’s arms.

***

Tell the truth.

Medicine encircles everything, all-inclusive, never sep-arated, ever sacred, and always changing. Raven encircles the fire. You, too, are invited.