Judge Candace Savage chose this story as the runner up in in the creative non-fiction category of our fourth annual Writing in the Margins creative writing contest. Our fifth annual writing contest will open in September 2015.

It suddenly hit me, one day there was a partial eclipse of the Sun. I realized the Sun is a god whose face you cannot regard full on. How many beings will make you blind if you look at them? Not many, just the Sun.

If you want to look at a galaxy through a telescope, say, you can’t even see the glowing conglomeration of suns if you look straight at the fuzzy blob in the eyepiece. You have to slyly look from the corners of your eyes and then the brightly spinning world floats into view.

I’m wondering about all those things, a fire in the sky that doesn’t burn out, a world of suns that spins in spiral eccentricities, a million billion, a googolplex, a shower of yellow, white, and black birds in the yard with trills (the white feathers are not white in bird eyes – birds see a glowing purplish hue). I’m wondering how many more things cannot be seen by looking directly.

Staring into the lights of this universe doesn’t make you blind, it makes you realize you already were.

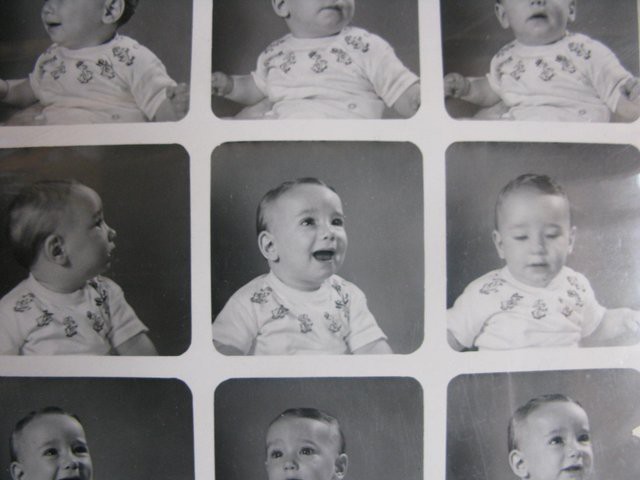

One thing I do know is watercolour painting, or I used to. It’s a backwards style of painting: you don’t pile on the paint, you start by imagining where the paper will show through the object – if the paper is white, you leave enough white. That unpainted surface represents light. Then the paint itself is diluted to allow light to reflect off the white paper, through the paint, back to your eye, and it has this radiant quality. It reminds me of baby pictures. This unpainted kid looks out at you, and you just wish the world would leave enough of that to shine through, instead of painting over and over and over.

In one painting I was doing off my back porch in a really derelict house I rented, I lost all the paper in the paint, it was really thick, the paint, because the porch was overhung by an enormous fir tree with drooping branches. I left the painting to dry, it was all wrong, painted over like a seven-year-old after two years in public school. Then I came back in disgust when it was still wet and I scraped away at the paint to find the paper, the light. And using the stem of my brush I scraped until it was exactly the light filtered through a fir tree, and the dirty porch glass, and the broken pane, and everything a derelict porch should be.

I just wish people would leave that space in kids, imagine if that was left to bleed through. Or if it got painted over, I think you could scratch at it and get the light back.

There are baby pictures of Evan. Black and white, 16 squares about 2 inches each on an 8×10 glossy page. He is trying to manoeuver through a series of emotions, you can tell that was the idea, to stimulate him through surprise and happiness and fear and apprehension. And he tries a few faces in the squares, which are consecutive in time. Watching his eyes though, you can see they never change. He is maybe 18 months alive, not long at all, but his eyes are sad. They are stressed-out eyes after crying all night, after worrying about loneliness and big questions of alienation. Eyes transported from a future onto his baby pictures.

Evan, not too many years after the 16 photos were taken, was only about 5 foot 3 inches tall. His hair, which in the pictures is curly and yellow, has turned black.

He fashions himself after The Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers, a cartoon. He has long black curly hair, he wears aviator glasses, a jean jacket with sheep fur on the collar.

He has a new job he has made for himself. His drunkle is a pharmacist (and philanderer, among other things) who owns the pharmacy. Evan gets himself locked in the building one night and soon he is an actual drugstore cowboy, if that is a job. He robs pharmacies.

He robs veterinarians, he takes drugs, some of which are meant for humans.

I know all this because he told me about his job.

But this is where memory gets slippery. I don’t know what he told me and what is something from a film I saw. I never understood the “cowboy” reference unless it was the plaid shirt (thick, felt-like material) worn under the denim jacket, and maybe the motorcycle boots he wore.

Evan was small, and smaller without the boots. I have no doubt he could fit into small places. He was entirely made up of bone and muscle. I’m not sure why, but he never had any fat on his body and his muscles were tight all over, like ropes and cable. How could someone with that much muscle not be angry all the time? Like a spring or a bull, just waiting to jump through a fence.

Waiting for nothing to happen was what being young was like. It was a miserable time, a time when you could only make up things to happen, but they never would.

I have theories about how Evan got to be all muscle and a thief of drugs. I know some things that lead to theories, but this is not really about theory, it’s a story I have to tell, or at least I am making it seem like story, the kind where you read and read and wait for something to happen.

Underfoot, mice and tiny voles slip here and there into the grass. The ground is freezing, it actually feels harder to walk on, as though there used to be some give to the dirt and now the water in it is frozen. It’s like that with the most obvious things. They tell you in school – water, ice, vapour – but school makes everything boring, and they act like they actually know everything. Teachers acted like they had an answer for every question. But some days you’d kind of come to and think of a question they couldn’t answer. Then the whole school would fall down, the hallways built on the plan of a prison, the office of the principal just a sign on a door with a changing name, the bells, the fluorescent lights, the stairwells, the street outside with people driving by who are not in school. That’s when you realize there is a mystery and there is a magic they are trying to hide.

There’s that empty mind that can actually see. There’s walking around your town in the middle of the day on a Monday watching people live. There is realizing that you are invisible because you are too young to be walking around town alone in the middle of the day and that being invisible makes you the perfect observer of this town and these things you have been waiting to happen if only you are there to see them happen.

Some people on a bench on a hill overlooking the whole town are drinking from a plastic bottle. They see you and they wave you over. A party on the hill and people who see you. The whole town spread out below, humming. The ground is freezing up and feels hard with every step. Mice and tiny voles shoot out from the path into the long grass on either side.

It’s a big plastic coke bottle and you take a swig. It’s coke and vanilla extract. They laugh at you and they are kind to you. They have the view.

Have you met that person who seems to be the conduit and the delta for generations of brutality? You know them, sometimes they are more charming and brighter than most people and yet – they really just want to get off their head. Sometimes they are of a higher intelligence than most people. I knew some people like that.

They always die young.

Evan was just like that.

From the moment he could get his hands on anything – alcohol, Valium from mom’s stash, boiled nutmeg in coke, opium – Evan was out of his head. He was out of his head on acid, jumping like a bean, bouncing off the walls, he was off his head on horse tranquillizers, stolen from a vet’s office. But to be fair, Evan was born a heroin addict and taken away from his heroin family for that reason, I guess, and now we know that whatever neurons he had in utero were ruined for pleasure right then, when he went through withdrawal at birth and became the perfect vessel for generations of pain. Of course, the heroin was a secret, and when they said heroin, I’m still not sure – I’m more of a mind to see his mom getting drugs at a doctor’s office and the heroin being Demerol. But illegal or legal, neurons get used to a thing like that and I hear that they never really recover. So Evan was sad. In the 8×10 16 squares of Evan at about 18 months, Evan is sad.

Sometimes when I think about Evan I think about him in the wheelchair, later, after he had a stroke because they wouldn’t give him painkillers strong enough after surgery. He was rubbing cocaine on his gums. He had a stroke and couldn’t walk or talk.

Sometimes I think about Evan waiting in his wheelchair. If he got high enough he could actually talk again. He would start talking as though there had been no years of silence, the voice in his head became audible and his stories spilled out again. If he was high enough. But that hardly ever happened.

And now I see they might do a trial of giving addicts some prescribed heroin. It’s like a falling away of rules once thought immutable. I think about a heroin prescription that would have made him able to talk.

That might have been a small miracle worth waiting for. But time has run out and Evan didn’t wait.