There are still dozens of Khiams around the world.

Let us never forget them and finally tear down those walls, once and for all.– Soha Bechara

Resistance: My Life for Lebanon

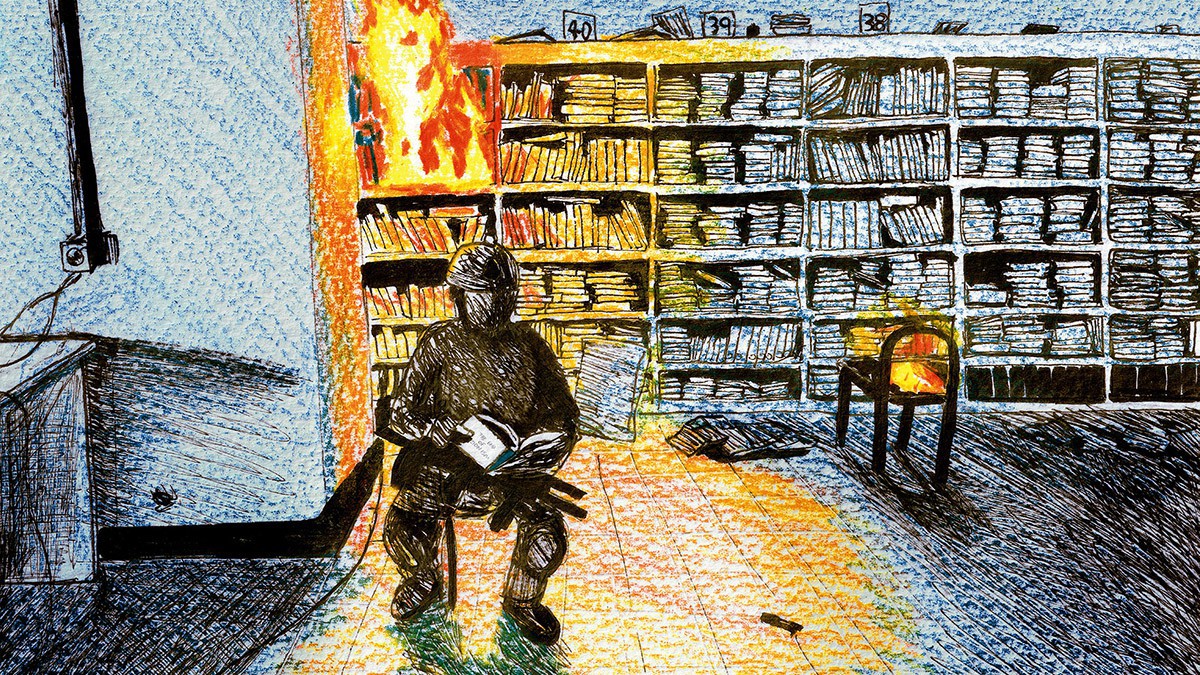

At the start of the Gaza genocide, as I first read of Israeli threats to bomb archives in Gaza, I received an urgent appeal from brilliant librarian, Ghada Dimashk, at the American University of Beirut’s Palestine Land Studies Centre. She was looking for assistance archiving social media and webpages of citizens and journalists documenting the genocide as the internet was constantly being shut down in Gaza and Big Tech censorship of Palestinian content was in full swing. My response to her was immediate and unequivocal: “Whatever you need, Ghada.”

Soon we launched the Gaza Genocide Digital Archive to collect and preserve Telegram channels, tweets, Facebook content, and webpages documenting the genocide in Gaza, especially content created by the people experiencing it. Then we brought together international partners and local organizations in Palestine and Lebanon to rescue and recover damaged and destroyed archives and protect those at risk of destruction. With allies, we launched educational seminars and reading groups, and released solidarity statements.

Throughout, we centred and amplified the perspectives and leadership of Palestinians and local communities. All the while, we struggled, like most of our collaborators, to find the words and means to cope with the horrendous archival and cultural dimensions of the genocide – let alone its unbearable human toll. The destruction of the material traces of the Palestinian people on their lands is a continuation of their physical elimination as an indigenous population from that land. It is difficult, in light of this, to find professional niceties or abstract academic frameworks that adequately respond to the incredible cruelty and horror of what is taking place.

Instead, we must turn to the resistant history, culture, and practices of the Palestinian liberation movement and allied movements in other sites of Zionist aggression and resistance, such as that of neighbouring Lebanon. From posters and mass commemorations to movies and living memory, such resistance archives counter Zionist colonization by preserving the histories and lessons of our land, societies, and struggles. They are a source of important information about who we are, what solidarity means, and the possibility of liberation and return. They also help us cope with the sense of time as both ruptured and repetitive, a common experience of colonized people, by teaching us the most important lesson of all – hope.

This hope is rooted in a desire for liberation and return that can neither be reasoned with nor suppressed, no matter the horror, violence, or odds, because it is forged from our abiding love for our lands and one another.

Counter-archiving as resistance

As Dimashk and I worked, we watched livestreams of the cultural dimension of the genocide alongside the suffocating siege, relentless massacres and bombardment, and near complete deprivation of the necessities of life. In the first month of the genocide alone, Heritage for Peace and the Arab Network of Civil Society Organizations to Safeguard Cultural Heritage (ANSCH) documented destruction and damage of nearly 104 archaeological heritage sites. In January 2024, Librarians and Archivists with Palestine (LAP) reported that Israeli Occupation Forces (IOF) destroyed the Central Archives of Gaza City which held 150 years of records; the Omari Mosque and its library, which housed a collection of rare books; and, after the IOF had looted historical artifacts, the Al-Israa University Library and National Museum. LAP’s report also names some of Gaza’s memory workers martyred in these attacks: Abdul Karim Hashash, Bilal Jadallah, Doaa Al-Masri, Dr. Jihad Suleiman Al-Masri, Iman Abu Saeed, and Marwan Tarazi.

These examples are a tragic testament to the settler-colonial drive to eliminate Palestinians both physically and figuratively from their land. It also shows how the destruction and theft of archives and heritage has been accompanied by the killing of their creators, curators, and caretakers. As part of the Student Intifada, New York University students commemorated this loss by establishing a liberated zone in their central library named the “Diana Tamari Sabbagh Library” after the IOF destroyed the extensive library of the same name in Gaza while hundreds of displaced Palestinians sheltered within.

The struggle over memory, then, is a life-and-death struggle for indigenous and colonized people. Zionist ambitions cannot be fully realized if the knowledge of what has been lost – documented in archives, records, texts, and archival traces – is preserved and remembered within and across generations.

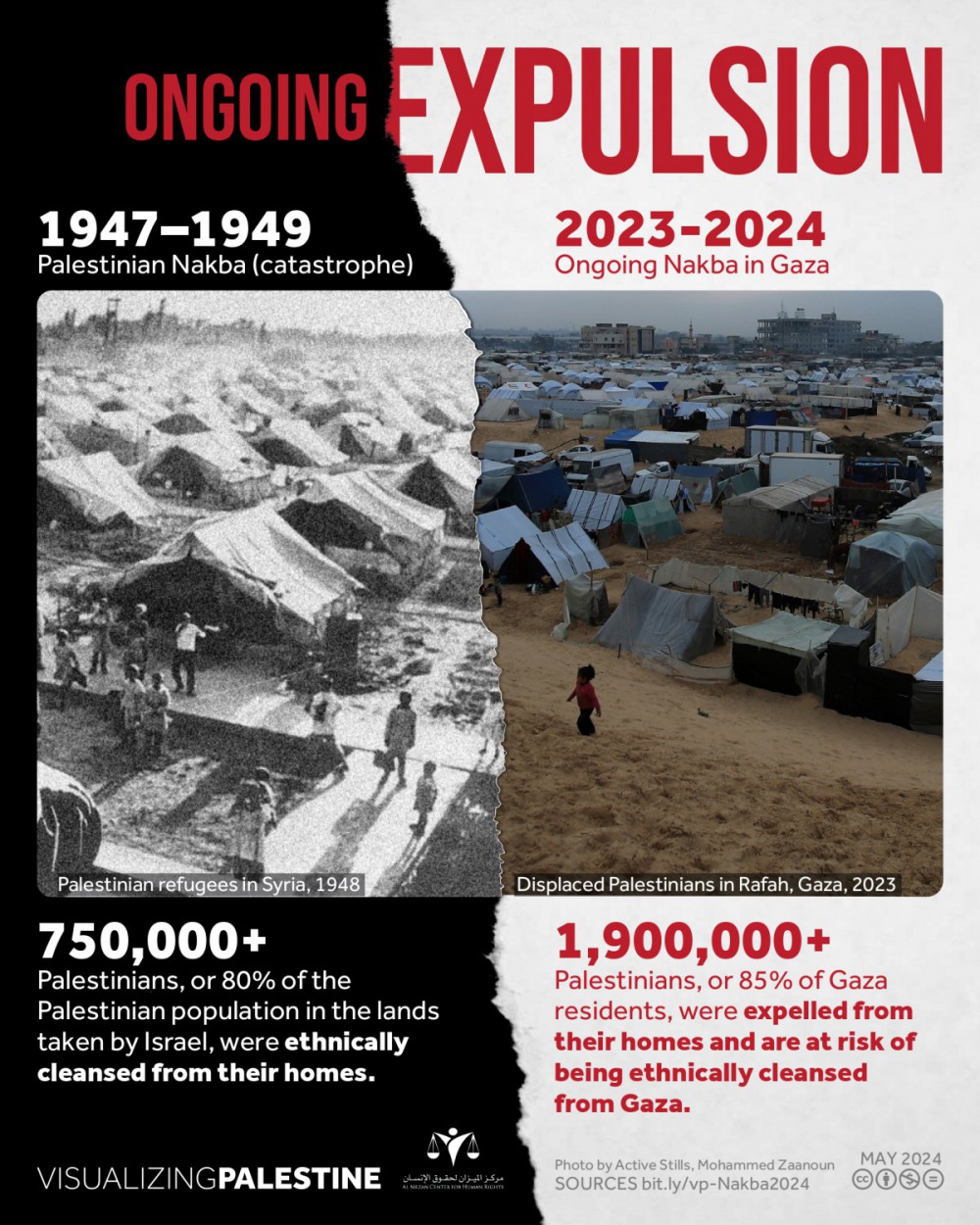

On May 13, 2024, Eman Alhaj Ali warns that “[k]nowledge is literally going up in smoke” because Gazans are, understandably, needing to burn their personal papers and books, as well as thousands of books in Rafah’s Bahrain Public Library, in order to stay warm and cook. Rula Shahwan has also reported that even the servers with digital backups of Gaza‘s university records have likely been destroyed, alongside the paper originals. Image courtesy of VisualizingPalestine. The forced displacement of Palestinians in 1947 during the first Nakba is contrasted against the current ongoing Nakba.

These accounts also gesture at what is at stake in this erasure, which is the reality of a different Gaza than that fabricated by Zionist and Orientalist white supremacist fantasies. This Gaza has a rich history and identity that is pluralistic and multilayered, shaped by its role over centuries “as a crucial gateway between Asia and Africa,” in the words of the organizations Heritage for Peace and ANCSH. The systematic targeting of historic, cultural and religious sites by Israeli aerial strikes or shelling is an attempt to erase Gaza’s pluralistic history to create a blank slate on which to write an exclusivist, ethno-supremacist colonial narrative where Palestinian culture is erased and which falsely rewrites European settlers as natives.

Alongside such destruction and theft, Palestinians and Arabs face often insurmountable barriers to access records by or about them through a two-tier native/colonialist system. It is what I define as a form of archival apartheid and is exemplified in the racist access and cataloguing practices of Israeli state archives that create a racial hierarchy to facilitate land theft and indigenous dispossession. In response to this archival apartheid, to the relentless destruction and theft of archives and historical documents, generations of Palestinian and allies have cultivated a powerful counter-archive that speaks back to the Zionist lie of a land without a people for a people without a land. This includes the foundational work of Palestinian historians and feminists like Drs. Salman Abu Sitta, Rosemary Sayigh, Nur Masalha, Nahla Abdo, and Rabab Abdulhadi, whose decades of interventions have shaped my thinking in this piece.

The scope of this resistance archive (arsheef al muquwama) is breathtaking. It encompasses digital repositories, oral history collections, teaching initiatives, and archival research centres, as well as the personal papers of anti-colonial figures like Dr. Constantine Zurayk (who coined the term “Nakba”) that I archived at the American University of Beirut. It includes sites of memorialization for massacres, imprisonment, and martyrdom, numerous posters, banners, graffiti, and murals on walls and in public squares from refugee camps to steadfast villages and towns. This resistance archive consists not only of objects and records but also the millions of Palestinians who refuse to forget Palestine, and the people of the Arab region who in their tens of millions refuse to normalize with Zionism, and the many millions more around the world who align with these refusals.

As in all settler-colonial contexts, from Palestine to Turtle Island (North America), from South Africa to Japan, when “the history and relationship between a native people and their land is forgotten, when settler amnesia prevails, then there is no one who even knows that there is anything to dispute or survive.” The struggle over memory, then, is a life-and-death struggle for indigenous and colonized people. Zionist ambitions cannot be fully realized if the knowledge of what has been lost – documented in archives, records, texts, and archival traces – is preserved and remembered within and across generations.

The Lebanese resistance archive: a world beyond empire

For many of us, the current Zionist horrors unleashed in Gaza, across Palestine, and in surrounding countries like Lebanon invariably recall other massacres, sieges, invasions, occupations, and bombings, as well as resistant hopes, liberatory visions, and anti-colonial victories. At a vigil for Lebanon and in solidarity with Palestine that took place in Kjipuktuk (Halifax) on April 7, 2024, a young Lebanese woman, Lama*, recounts the hundreds of martyrs fallen in Lebanon since October 2023, the tens of thousands displaced, and the millions of square metres of burnt forests and olive fields. She explains:

This violence […] can be traced back [...] to 1948 […]. While the occupation forces were forcibly displacing, terrorizing, and ethnically cleansing […] Palestinian villages and towns, the same war doctrine was again utilized on Lebanese lands. From the 1948 Hula Massacre to the 1965 occupation of the Shebaa farms, the 1970 attack on Arqoub, Marjayoun and Bint Jbeil, to the occupation of Southern Lebanon from 1982 to 2000, the First and Second Qana Massacre, and the July war in 2006 and the months and years in between filled with loss and destruction. A loss of precious life, a destruction of history and culture, and eradication of the land.

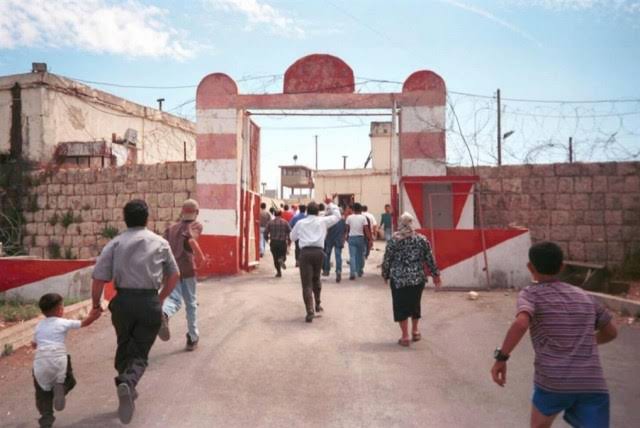

The layering of history and analogy is too much to bear in moments that can feel like uncanny echoes of all that has come before. This is a second Nakba, we hear, and “one heart cannot bear two Nakbas,” writes Gaza’s Hanin Elholy. Walking down my street in Beirut as winter set in, I watched the children singing for Palestine while swinging their little lunch boxes on the way home from school. Hope tightens around my heart as I recall the thousands of children we have lost, the thousands we may yet lose. I read news of Israeli bombs killing freed Lebanese prisoner Nassifeh Mazraani on December 1, 2023 in Hula, and recall the extraordinary day in May of 2000, when Khiam, the prison where she had been incarcerated, was liberated. Khiam’s liberation came just two days before the full liberation of South Lebanon had been achieved (except Shebaa Farms).

On May 23, 2000, people woke up in Lebanon to the incredible news that the IOF had began withdrawing after 22 years of occupation. Thousands started driving and walking south to their villages and towns, and thousands more joined them throughout the next two days as the IOF retreated from more territory. They tore down barriers to reach their liberated homes and lands. They danced and sang in the streets and fields. Embracing and kissing, they ululated and threw rice, as if at a wedding. To see the happiness on those long-suffering faces from those days is utterly disarming.

About 3,000 unarmed civilians, Soha Bechara writes, “butted up against the cell doors. They broke open the locks, bringing back to life haggard men and women who were [astonished] by this sudden reversal of history.” One hundred and forty-four prisoners were liberated that day from that hellish place, where over 5,000 Lebanese, Palestinian, Arab, and Kurdish men and women had been imprisoned over the years.

The legendary Bechara spent a decade incarcerated in Khiam and, like Mazraani, resisted the horrors of that torture centre, leaning into and cultivating a defiant ethos from behind the empire’s bars, one that makes our prisoners the backbone of the anti-Zionist struggle. These stories of freed prisoners and liberated lands are powerful emblems of hope and promises of future liberations. During the 2006 War on Lebanon, the Israeli state bombed Khiam to erase traces of Israel’s crimes and defeat. Still, thousands defy that violence by continuing to visit and remember.

There is a world beyond empire.

Image from the liberation of Khiam in May of 2000. Photo courtesy of Samidoun.

So too, in defiance of the war on memory, we mark liberation day annually on May 25 with massive celebrations, especially in South Lebanon, which we have called Jabal Amil – long before the colonial schemes and cartographies of Sykes-Picot and the Balfour Declaration divided us from ourselves, carving us into nation states like Lebanon, Palestine, Syria, Jordan, Iraq, and Egypt. Before then, ours was one open territory, stretching from the Euphrates to the Nile and beyond. Marking liberation day in Lebanon also reaffirms our commitment to liberate all Arab lands from Zionism and to wrest back our region from imperialism. When we remember that the Zionists have invaded all the surrounding countries and continue to occupy land not only in Palestine but also in Syria and Lebanon, and that they have and continue to support oppressive regimes and colonial projects around the world, we de-exceptionalize Palestine.

We also better understand who we are and what we must do, as when the younger Lebanese generations learn about the history of Zionist occupation and the liberation that the world had declared impossible. We then see ourselves as agents of history who have achieved something remarkable, if incomplete. We are also reminded why we will never give up on the liberation of Palestine – first, because Palestine is a just cause; and second, because our histories of struggles and horizons of liberation are inextricably intertwined. We rise and fall together. The connections are multifaceted: the steadfastness and victories of the people in Palestine shields Lebanon, while the Israeli defeats in 2000 and 2006 in Lebanon weakened the Zionist state by curtailing its push for a Greater Israel from the Euphrates to the Nile. Even as Lebanon cradles the Palestinian forces, many of the most important Palestinian leaderships and organizations were launched from Lebanon. Similarly, many of the Lebanese forces today were first trained within the ranks of the Palestinian forces in Lebanon. Both also have shared roots in the Arab Nationalist Movement of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Memories and histories of our shared struggles are dangerous because they show us the power of coming together and teach us important lessons about dealing with problems. But as we see daily, uniting anti-colonial and liberation forces is needed to resist the global scale of empire on which Zionism depends. Building and sustaining these solidarities and connections is a profound act of love for our families, societies, and lands. We see such love on public display daily for Palestine in Lebanon and wherever people organize against the Israeli genocide. Here is my public display of love – stories from the counter-archive of land liberation and return in Lebanon to hold forth visions of hope and future liberations and returns of Palestinians.

These stories I send with love and gratitude from Jabal Amil to Gaza, whose sacrifices and legendary sumud (stalwartness) for the liberation of Palestine, the region, and the world from Zionism will always be remembered.

Jamila Ghaddar

Al Aqsa Flood Day 236

June 6, 2024

*We are not sharing Lama’s name at her request because of the vulnerability and safety concerns of her personal situation.

_780_520_s_c1.png)

_780_520_90_s_c1.jpg)