Globalization has propelled neoliberalism across borders, not just as an ideology or system of commerce, but as the primary determinant of the daily realities of where people live, what they eat, how they work, and what rights they enjoy. The deregulation of economies in the service of free trade — be it the reduction or elimination of taxes and tariffs, the weakening of employment and environmental standards, or the privatization and outsourcing of social services — continues to displace and disenfranchise people across the globe. Moreover, the perennial competition to attract capital has pushed employers to divest themselves of accountability for the rights and needs of their workers, creating an increasingly insecure and exploitable workforce in the service of business elites.

While precarious work and displacement have never been more widespread, globalization has also connected workers as never before, and they are responding to the next wave of global capitalism with unforeseen innovation and collectivity on many fronts.

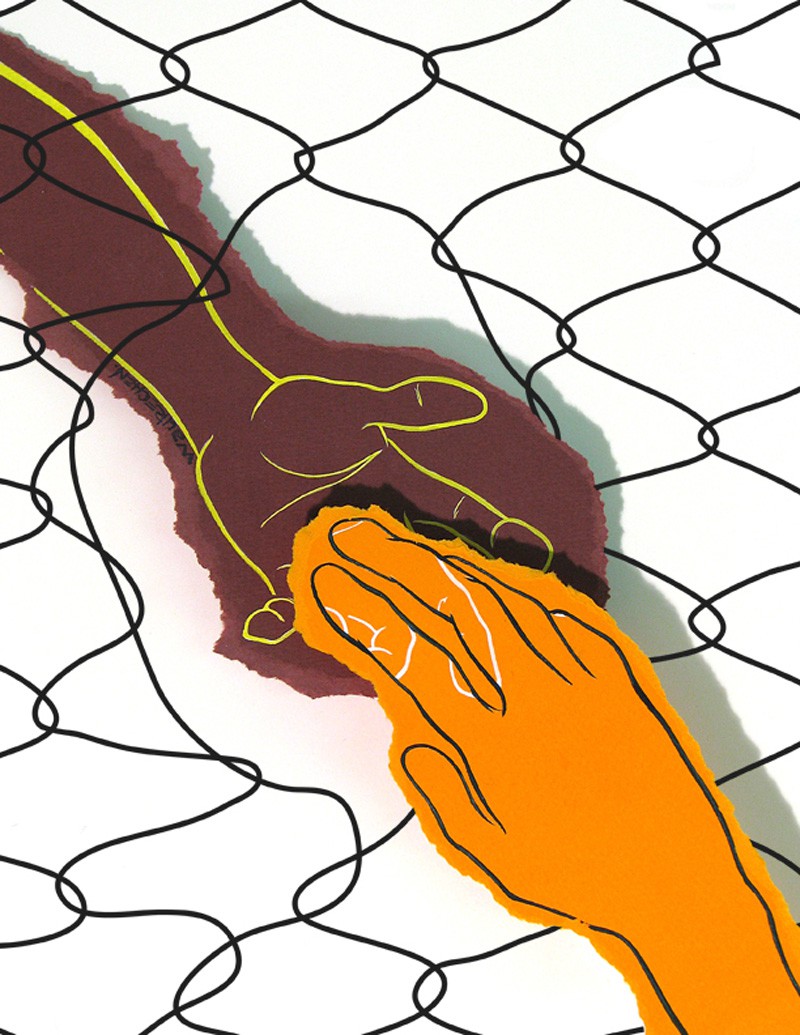

The other worldwide web

A growing network of migrant workers, families, villages and sometimes-criminalized organizations is taking shape to provide material and informational support to migrant workers. Material support could come in the form of a job connection, a place to stay, or help crossing a border, while useful information includes which countries are easiest to get into, how to find employment, and how to evade local police. The ability of exploited workers to undermine borders and the security state is evident in the informal organizing already taking place.

The state has adapted to the success of these forms of resistance with the creation of the “virtual border” to contain and exclude migrant and mobile workforces. This expansive system of checking migrants’ papers in schools and hospitals, denying them access to services and deporting those caught without documentation is an ethereal, mobile border that follows migrant and informal workers, limiting their access to both space and rights.

Projects like No One Is Illegal, Solidarity Across Borders, and other migrant solidarity movements, together with the efforts of both traditional and community-based unions, strike at the virtual border by offering migrant workers means of representation and a channel to negotiate with bosses and legislatures. This approach does not sidestep immigration laws completely, but it does bridge the gaps between the traditionally white and male labour movement, a marginalized workforce that is largely racialized and female, and a government that has long considered itself exempt from responding to the needs of non-citizens.

Workers in precarious jobs are engaged in a constant battle against isolation and objectification, both in the physical workspaces and in the dominant culture. Precarious workers, who may not have citizenship, do not have the luxury of rights that humanize workers and protect their bodies and minds from the rigours of exploitative work. Workers who are exempt from employment standards legislation face reduction to the level of commodity — labour to be traded, often between countries, with human needs regarded as financial liabilities to employers and governments who rely on cheap labour.

The virtual boss

Informal and migrant workers have necessarily expanded the concept of employer to reflect the realities of precarious work. A union for street vendors bargains not with a central employer, but with local police and the municipal government. A union for migrant workers must bargain on two fronts: with the workers’ employers, and with federal legislators who determine immigration and labour law. Necessity aside, it is a revolutionary model for organizing in informal contexts. In the absence of a traditional employer-employee relationship, the potential for workers to engage directly with authority, in whatever form it takes, is revealed. In this context, the “employer” is whichever authority determines the place, hours and methods of work, be it a boss or a state.

Precarious workers’ movements are providing models of resistance to the objectification and isolation of exploitative systems of employment in other ways as well. While social media raises red flags for many activists who worry about online-only movements, a calculated use of new technologies offers an opportunity to educate large audiences quickly and bring invisible workers to the fore, where they can be seen as more than a pair of arms on a farm. The social networks taking shape, in both virtual and physical spaces, are inherently humanizing.

Case study: The Street Vendor Project

Alex Diceanu, a PhD candidate in Global Political Economy at McMaster University, explains that “places like New York City have become highly polarized, with high-earning professionals purchasing services from precarious workers who depend on low-cost goods provided by sweatshops, small businesses and street vendors.” Diceanu researches the rise of precarious work in developed countries, focusing on new forms of resistance among workers in major cities, and has also worked as a labour activist for the last five years. As chair of Workers United, a workers’ action centre based in Hamilton, Diceanu’s excitement about the capabilities of precarious workers and their willingness to engage in struggle make it clear that the real story is not the ugliness of global capitalism, but the power of workers to resist.

New York City’s Urban Justice Center runs several projects aimed at organizing workers on the edge of casualized and informal work, including sex workers, homeless people and street vendors. Among these initiatives is the Street Vendor Project (SVP), which uses a mixture of education, legal advocacy and direct action to support street vendors and protect their civil and labour rights.

In New York City, as in many other cities across North America, street vendors are largely an immigrant population. Precarious immigration status and language barriers are significant obstacles to labour organizing. SVP’s education projects focus on informing workers of their rights, building their capacity to defend these rights against attacks from police, and ultimately influencing the legislation governing their work.

SVP’s educational work also extends to the broader community. Making excellent use of new media, SVP’s documentary-style informationals communicate the importance of vendors to the local economy, the precarious working conditions and harassment from police that vendors experience, as well as the relationships between vendors and their communities. This is an important tool of SVP’s organizing, and a medium to describe how the intersections of immigration systems, neighbourhood and municipal economic policies, as well as race and class-based barriers impact the vendors who live and work in New York.

In a video titled “Street Vendors Keep NYC Healthy” project director Sean Basinski describes efforts to contain street vendors, and the means by which they are shut out of many communities. “A hundred years ago, most vendors in New York City were concentrated in poor neighbourhoods” Basinski explains. “But now you see them mostly in more affluent neighbourhoods.” The video identifies the city’s cap on vending permits as the cause of the shift; with only 3000 food vendors serving the entire city, vendors tend to locate in wealthier areas where profits are highest. With rents on the rise in low-income neighbourhoods, driving out small grocery stores, access to affordable fresh fruit and vegetables for the large populations of racialized and immigrant communities has become an issue. The lack of vending permits prevents vendors from supplying these neighbourhoods with an alternative to grocery stores prices.

By educating community members, who are likely to support vendors because they provide access to affordable food and goods, SVP is able to build their lobbying base, increasing pressure for changes to legislation. By empowering vendors to resist unfair arrests, and also mobilizing broader community support to defend the rights of vendors, SVP’s educational work is also a defence against displacement.

Case study: Justicia for Migrant Workers

Over 16,500 people travel from Mexico and the Caribbean each year to work on farms in Ontario, where they constitute more than half of the province’s agricultural workforce. Migrant workers live on the farms where they are employed for the spring, summer and early autumn months, turning the farms into mini-metropolises. Without adequate access to public transportation, trips into nearby cities are infrequent, and farm workers are often entirely dependent on their employers to meet their basic needs, with food and housing typically deducted from their wages.

Justicia for Migrant Workers is a collective of activists who strive to defend the rights of migrant and non-status farm workers, with chapters in Vancouver, Toronto and Guelph. As allies, members of Justicia fight to create space for workers to articulate their concerns without the risk of being fired or deported, and seek to take leadership from the experiences and knowledge of migrant workers themselves.

Part of Justicia’s work includes working within the legal system to challenge legislation that contributes to the dangerous and exploitative working conditions faced by migrant workers. Since migrant workers are regulated by immigration law, temporary foreign worker programs and labour law, it is a complex arena for activism. Groups like Justicia can provide opportunities to voice the concerns of migrants and other disenfranchised residents in legal and cultural spaces usually reserved for citizens only.

Fraser v. The Attorney General of Ontario, a constitutional challenge brought forward by three migrant farm workers, together with the United Food and Commercial Workers Union, has been to court six times in the last 11 years. At the heart of the challenge is the violation of farm workers’ rights to freedom of association and equality — and specifically, the right to bargain collectively — by Ontario’s Agricultural Employees Protection Act (AEPA). The AEPA, which requires employers to listen to the representation of unions, but not to bargain with them, was passed in 2002 under the Harris government.

As intervenors in Fraser, Justicia argued that “the combination of both precarious employment and immigration status denies migrant workers the ability to exert their rights.” Without specifically legislated protection, argued Justicia, the “arduous, exploitative working conditions and living conditions” of migrant farm workers puts them at a disadvantage compared to workers with permanent status in Canada. When the combination of non-citizen status and temporary foreign worker legislation neutralizes any claims migrant workers might have made on the basis of racial justice, a responsibility on the part of the state to protect the workers’ right to collective bargaining and free association is a meaningful tool for workers whose collectivity is key to their struggle against precarity and racism.

While government lobbying and legal challenges are undoubtedly an uphill battle, especially for workers with few or no recognized labour or citizenship rights, there have been important victories. Earlier this year, the Supreme Court of Canada ruled that the Agricultural Employees Protection Act does in fact violate the right to freedom of association in the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. The Supreme Court also affirmed that freedom of association includes collective bargaining, and that it is not enough to merely allow collective bargaining; the government has a responsibility to actively protect that right.

Participating in the legal system is a long and exhausting process, with no guarantee of a victory. For many activists it is counterintuitive to hand workers’ power over to legislators and judges, who do not necessarily have workers’ best interests at heart. But groups like Justicia for Migrant Workers force the voices of those who have been denied citizenship into the discourse of policy-makers. Changing or expanding a legal definition, such as freedom of association, sets an important precedent for future legal action, and results in concrete changes to working conditions.

Recreating community spaces

Among communities of precarious workers, people are finding new ways to connect. Whereas industrial capitalism brought workers together in factories and working-class neighbourhoods, today’s capitalism isolates and divides workers. The challenge, to which workers centres, migrants’ rights organizations and community or industry unions are rising, is to recreate those spaces in ways that match workers’ realities.

The combination of the migrant “worldwide web” and the new media of the Internet provides a vast social network for information sharing and community building. Workplace and industry blogs, YouTube posts and social media offer workers the opportunity to develop a language and means of communication with which they can document and describe their working conditions and movements for change.

Physical spaces can also be generated in the communities where workers live. As chair of Hamilton’s Workers United, Diceanu is attempting to build such a network, pointing out that immigrant workers have always been at the forefront of creating community spaces by using existing ethnic and religious networks. A workers’ centre can serve a similar function, says Diceanu, providing “a net amidst all this mobility that can capture people together in ways the workplace no longer does.”

The optimism of organizers in the precarious workers’ movement is indicative of the innovation and strength of the movements detailed above. Organizations like Workers United, No One Is Illegal, New York’s Urban Justice Center, and Toronto’s Workers’ Action Centre are drawing traditional labour unions into their struggles for global justice, reorganizing not only workplaces, but the movement itself, as they work to find the issues and organizational structures that bring people together. There is potential in the movement, beyond just making neoliberalism tolerable: acting across and between physical and ideological borders, the organizing efforts of precarious workers and their allies are crystallizing in a new social movement that is part labour, part community, and part environmental.

“I’m really amazed by the ability of exploited workers to respond to capitalist attacks” says Diceanu. “Even when they’re disoriented, people are constantly reinventing struggle.”

_780_520_90_s_c1.jpg)