A communications specialist and intrepid freelancer, Dave Mitchell worked as Briarpatch editor from 2005 to 2010. In the short time since his retirement from the magazine, Dave has co-edited the book Beautiful Trouble, spent time in Mexico City researching the political uses of the war on drugs, worked as director of communications and policy development for Ryan Meili’s recent campaign for leadership of the Saskatchewan NDP, and guest-edited an issue of Briarpatch. In between bouts of hyperactivity, you can find him calmly contemplating Buddhist ethics over a pint of Guinness.

When I started at Briarpatch in 2005, I was 28, over-educated, under-qualified, disenchanted, and suspicious of any organization that had the money to pay a decent wage.

I was, in other words, a perfect (mis)fit for a magazine that was determined to change the world by force of wit, analysis, investigation, edgy design, and sheer tenacity. Briarpatch was my dream job, and I threw everything I had into it.

The workload and learning curve were daunting enough that I briefly contemplated setting up a cot in the attic of Huston House, where Briarpatch is based, in lieu of renting an apartment – I was at the office most of the time anyway. Fortunately, I eventually found a more sustainable work-life balance as we shifted to a more realistic publishing schedule and found ways to share the workload with some very talented volunteer copy editors and proofreaders.

When I started, the magazine had yet to fully enter the digital age. There was only one computer in the office with access to email and the Internet – it was kept in a corner of the administrative assistant’s office, quarantined, for fear of viruses, from the editor’s and administrator’s i486 computers on which most of the actual work was done.

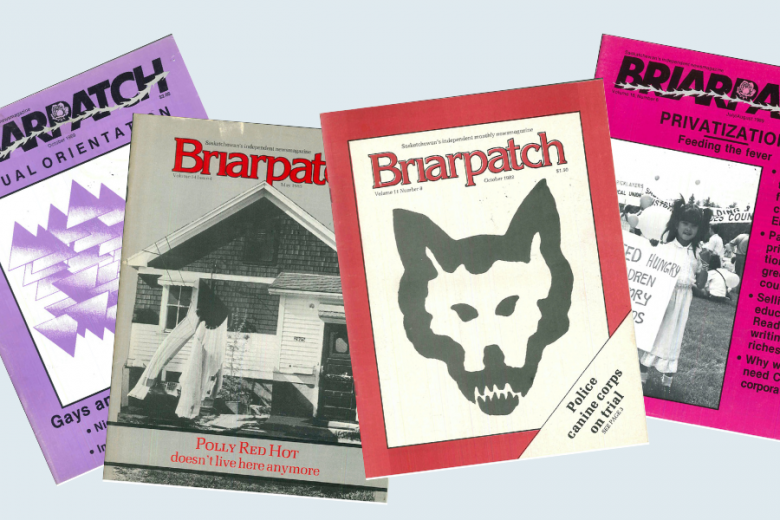

Briarpatch has always been a labour of love, and I believe that’s the key reason for the magazine’s unlikely success. It consistently leads with the heart, and so it’s able to produce quality journalism with a tragic fraction of the masthead depth of most publications. From the writers and illustrators, to the staff and board, to the subscribers and sustainers, hundreds of people over the years have given their all to produce quality content designed to incite, inspire, provoke, and harangue readers into action for a better world.

Clare Powell has clocked more than three decades as an active contributor to Briarpatch, filling almost every role we have, including writer, editor, board member, envelope stuffer, and podcast host. After retiring from a long career in the labour movement in 1999, Clare remains active as an anti-nuclear activist, a Briarpatch volunteer, and host of Eclectic Café on CJTR Community Radio 91.3 FM, where he kicks back to the likes of Ella Fitzgerald and Peggy Lee.

How did you come to work at Briarpatch?

I had been working in radio for about 10 years. I started out in Flin Flon, Man., and went to four different stations in Manitoba before moving to Regina to work for the CBC for a year. I spent a short time working for the provincial government before getting into a dispute with the NDP over their support for nuclear power.

I don’t know how long I’d been buying Briarpatch but when I saw that they were looking for an editor, I applied. I think I was the only one.

What did the production process look like in 1979?

Quite different. We had an addressograph, a steel machine that stamped out lead address plates and weighed a ton. We got it over here in the back of a truck and had to set up a pulley system to haul it up the back fire escape with about five guys on the end of a rope. It was immense. We used a typesetting machine and pasted sheets of text and headlines onto each page by hand.

You came on as the editor immediately after the NDP government cut Briarpatch’s $54,000 annual funding, which comprised about two-thirds of the magazine’s budget at the time, ostensibly because it had “lost touch with its low-income origins.” Presumably, Briarpatch’s criticism of the Blakeney government’s pursuit of uranium mining and nuclear development, and its cuts to day-care and legal aid, had much to do with it.

We were all onside when it came to opposing the uranium industry. But we also started covering more union issues, and while the NDP was allegedly not anti-union, there were a lot of anti-union people, and they didn’t like the emphasis on defending the rights of union members. I suspect that was part of it too.

We had to cut back to a four-page newsletter for one month in September 1980. But we were back full-swing in October. We appealed to our supporters, and money came in. That was the only time that the magazine hasn’t published. I don’t know, quite frankly, how we managed. One person, Bev Crossman, laid herself off. One thing we did was set up the typesetting company, First Impressions, which brought in quite a bit of revenue for a while. All of us would go out to try to get business. It wasn’t easy. We just muddled through.

You didn’t skip a beat in taking the Blakeney government to task. You wrote in the first issue after the funding cut was announced that the NDP government was far from its posturing as “champion of the downtrodden and disadvantaged” and that it was content to “patch up and plaster over the most gaping inequalities in the capitalist system.”

I was very colourful, yes.

There are two schools of thought. One is that government should be neutral and provide funds for magazines. The other is that if you’re reliant on government for funding, chances are that you’ll back off from criticism, which we never did, and we paid the price.

You’ve described Briarpatch as a “champagne magazine on a beer budget.” An alternative tagline recently suggested by former editor Dave Mitchell was “scraping by since 1973.” What do you think has kept Briarpatch going for 40 years?

It’s never just the people in the office. People used to pop out of nowhere and send us articles … 90 per cent of them were better writers than I was. They didn’t get a penny. We just couldn’t afford to pay them. But they just kept coming and coming. Many of these dedicated people are still here in Regina. I’ve had a lot of disappointments with politicians and other people in my life, but not with Briarpatch.

Educator and trade union activist Adriane Paavo worked as editor of Briarpatch for three stormy years in the 1980s, during which she fended off the collective wrath of business, government, and mainstream media interests. She now works as an education officer for the Saskatchewan Government and General Employees’ Union and also kayaks and quilts. She continues to be a sustaining subscriber and active supporter of Briarpatch.

Grant Devine’s government in the 1980s gave Saskatchewan its first taste of neoliberal casino capitalism. While we may be used to the card tricks by now – deregulation, privatization, tax cuts for businesses and the wealthy, a shrinking of the public sector – today’s players are smoother, more polished, and better schooled in how to make their moves without scaring the audience. In the 1980s, things were more flamboyant, more Wild West saloon poker than Monte Carlo baccarat.

Briarpatch worked hard to keep an eye on Devine’s hand, right from his election in 1982 through until when I was editor from 1987 through 1989. Two events stand out for me from those days.

In the first, I was heading home in a cab from the Regina airport, in a post-flight daze, when the driver mentioned that he too had just gotten back from a trip. He and some friends had been in Calgary putting together a deal to buy the publicly owned bus company, Saskatchewan Transportation Company. All had strong ties to the provincial Conservative party.

When I and Briarpatch volunteer Murray Dobbin started phoning around, saying we were with the party and had some money to invest, we found out a lot more. Fortunately the deal never happened, but it showed how the scent of big, easy money was in the air, and it wasn’t just attracting men in suits (see “Mike buys a bus company,” Briarpatch, March 1989).

The second event involved a group of the province’s top business leaders, academics, and lawyers who had formed the Institute for Saskatchewan Enterprise (ISE), a “non-partisan” organization dedicated to “stimulat[ing] public awareness of all aspects of enterprise from an economic, rather than a political, perspective.” ISE organized a major international conference to take place in Saskatoon in May 1990, billing it as providing definitive proof of the values of privatization.

Those were the days before the Internet. Using traditional public library reference systems and the help of Briarpatch volunteers John Warnock and Cheryl Stadnichuk, I found a trove of information detailing ISE board members’ self-interests in privatizing Saskatchewan resources and the track records of many of the conference’s experts (“With a little help from their friends,” Briarpatch, July/August 1989). At the conference, a team of people from the labour movement, Briarpatch, and the Action Canada Network spread the information to the media and conference-goers, giving the event a lot more attention than organizers wanted.

Those more innocent days, when the people wanting to gut collective, public mechanisms were honest and open about their greed, are over. Today, the stakes are higher and the players are global. Fortunately, the tools at our disposal to fight back and articulate an alternative are also more sophisticated, with Briarpatch, now age 40, among them.

Phil Johnson is an independent consultant in labour relations and human resources. He has honed his knowledge of Saskatchewan culture and politics through years of living in Aylesbury, Craik, Saskatoon, the Cypress Hills, and now Regina. Phil swims like a fish and has participated in Briarpatch’s swim-a-thon for each and every one of its 20 years. He is currently spearheading guerrilla-gardening actions in an unspecified area of the city.

My relationship with Briarpatch Magazine began in the early 1980s when I found a copy of this radical rag on the newsstand in rural Saskatchewan. I’ve been a subscriber ever since.

Between 1995 and 2010 (with a few years off in the middle), I spent many Sunday mornings and Monday evenings at meetings in drafty union hall basements and at Huston House (also drafty) as a member of the magazine’s board of directors. Of course, much of the time during and between board meetings was devoted to generating fundraising and story ideas. This was the fun part. The hard work of making the ideas happen usually fell to our staff, whose devotion to the magazine has always amazed me.

What has always appealed to me about Briarpatch is that it tells stories from inside the community. It digs deep and wide, offering perspectives that the corporate media ignore. It allows the people affected by public policy or corporate actions to tell the reader what life is like for them and what they believe needs to be done to get a little justice for themselves and many others like them.

Briarpatch is a far different magazine today than it was 40 years ago, or even 30 years ago when I first picked it up, but it still has that burning drive to uncover injustice and provide a vehicle for getting the truth out. It has expanded the discussion. Although it is no longer the 10-page forum for low-income earners, welfare recipients, and the unemployed that it started out as, these topics are still covered, and the philosophy of siding with the oppressed and impoverished remains. Over the years, there has been more than a little debate over whether Briarpatch should focus on Saskatchewan news or evolve into a national magazine, and it now covers local, national, and international issues.

The quality of research, writing, and editing is often superb. Looking at the last few issues, I have to note a couple of articles: “Defining Who is Métis” by Tara Gereaux and “Killers in High Places” by Dave Oswald Mitchell (former Briarpatch editor). They exemplify what Briarpatch has become. Both discuss timely issues of local, national, and international importance, both are by Saskatchewan writers, and both are thoughtful, thoroughly researched, and superbly written. Briarpatch has come a long way indeed, without losing any of its courage or principles.

Edith Mountjoy was born in a displaced persons’ camp in Denmark in 1945. She and her family emigrated from Germany to Canada in 1954. After her mother’s early death, she was fortunate to be raised by an intrepid woman, her grandmother, who showed her how to love the natural world and care about social justice. Her involvement with Briarpatch began as a volunteer contributor, and she went on to work as a staff member in the 1970s and again in the 1990s.

For an independent, Saskatchewan-based magazine to have survived for 40 years is a remarkable achievement. The only explanation for this success is that its founding message – that a better world is possible if we act together to bring it about – has resonated with its many friends and supporters throughout the years.

When Briarpatch was founded in 1973 by a group of unemployed people, it was to give a voice to those struggling against poverty, injustice, and oppression, to help fill the gap left by the mainstream media. As founding member Maria Fischer explained in Briarpatch’s 15th anniversary issue, the magazine’s purpose was to be part of a grassroots movement to challenge a system that preserves privilege and breeds prejudice. When Maria died five years ago at the age of 87 in Ladysmith, B.C., she remained a loyal Briarpatch supporter.

In the early days, funding to produce and distribute the magazine around the province was provided through a grant from the provincial government’s Department of Social Services. This funding was abruptly cut in 1979. Although the official line justifying the cut was that Briarpatch had lost touch with its low-income origins, the real motive, it appeared, was to muzzle the magazine because of its anti-uranium stance. The cut was not only sudden, but also retroactive, leaving the magazine in a precarious position. The Briarpatch collective appealed to its community for help with survival strategies. A Save the Briarpatch Support Committee was formed, and the community quickly came to the rescue.

Those were challenging, but also good, times as everyone worked together to stabilize funding. Benefit dances and banquets became a way to not only raise money but to build community and celebrate together for a common cause. A monthly donor program was established, and subscription drives were initiated. Briarpatch’s typesetting machine was put to use for contract work. Among the first to come on board was the University of Regina’s student newspaper, The Carillon, and the Retail and Wholesale Department Store Union’s newsletter, The Defender. This was the beginning of First Impressions, the typesetting and design arm of Briarpatch, formed in 1980 to take on commercial work to subsidize the magazine.

I returned to work at Briarpatch in the early ’90s when the magazine celebrated its 20th anniversary. By then, due to changing technology, First Impressions no longer existed. What remained was the continuing need to challenge the status quo. That need is even greater today, in a time of global corporate domination and a widening gap between rich and poor.

For 40 years, Briarpatch has remained true to its radical roots. It has spoken out strongly and courageously against injustice in all its forms. It has also provided a home for activists working for social change. I feel privileged to have been part of this movement and grateful for the many friends I met along the way.

_780_520_90_s_c1.jpg)