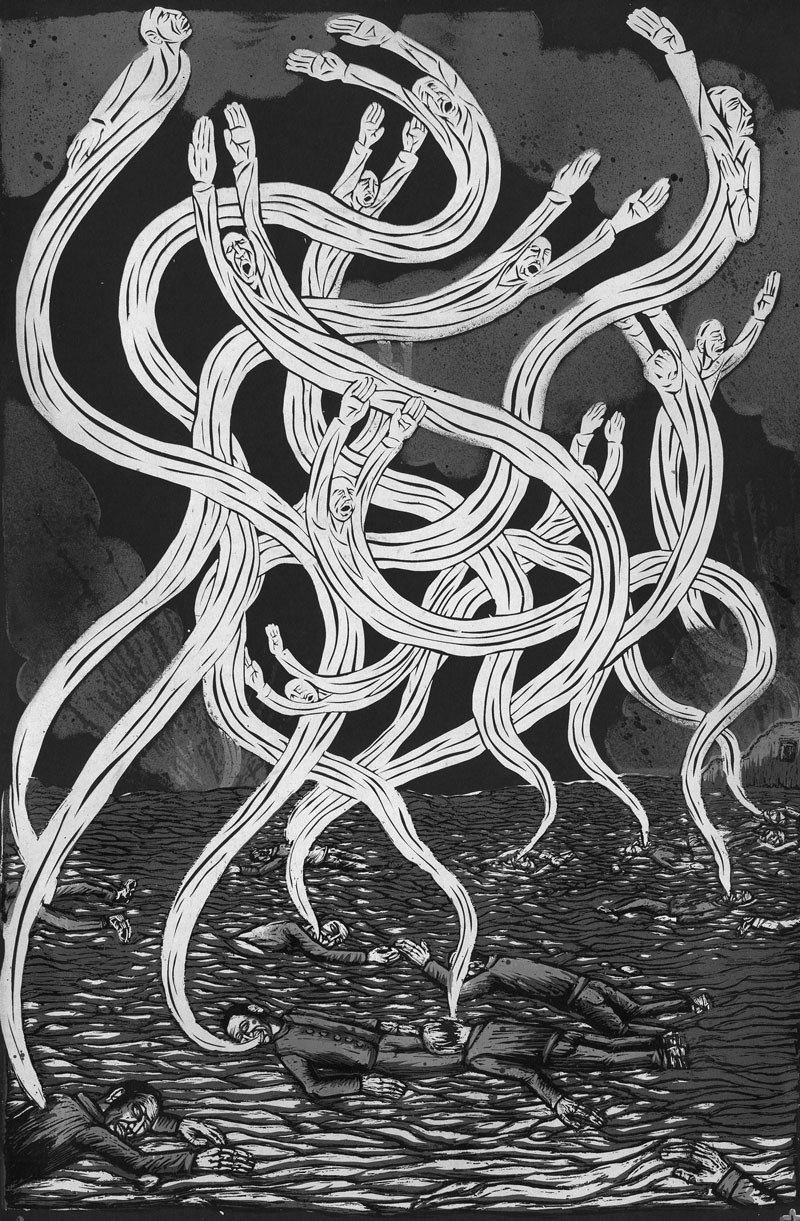

Dead Souls (2012) by Erik Ruin; Screenprint with spraypaint

Justseeds Artists’ Cooperative is a continental network of artists committed to making print and design that reflects, builds, and sustains the aspirations of radical social movements. With two dozen artists from the U.S., Canada, and Mexico, Justseeds is a worker-owned co-op where the sensibilities of individual artists coalesce in shared objectives.

Justseeds artists produce collective portfolios, contribute graphics to grassroots struggles, work collaboratively both in and out of the co-op, build large installations in galleries, and wheat-paste in the streets – all while offering each other daily support as allies and friends. Justseeds artists Erik Ruin and Meredith Stern spoke with Briarpatch about aesthetics and politics, empathy and influence.

What was the place or role of art during your childhood?

Erik Ruin: I didn’t grow up in a particularly creative household, though my father did dabble in poetry and was a big record collector. Every so often, he would enlist us kids to re-alphabetize all the stray records. As we sorted them into stacks, I would demand to hear the ones with more intriguing-looking covers. This introduced me to some great music like Pharoah Sanders, the MC5, and the Velvet Underground — and I think taught me about the relationship between form and content.

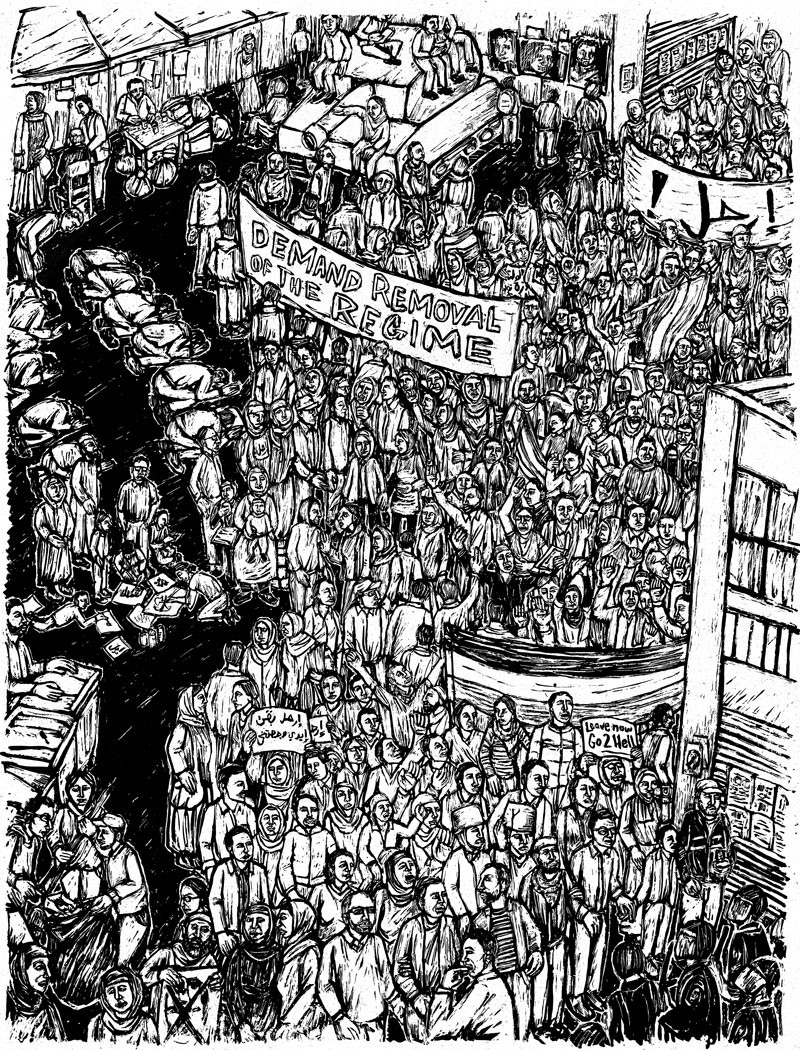

I often visited the Detroit Institute of Arts growing up in the Detroit area. There are a few pieces that really struck/stuck with me, but most especially Diego Rivera’s Detroit Industry Murals. These massive scenes of collective labour, with their allegorical shadings, and the sheer busyness of the whole thing, are very inspiring. In particular, the complicated schema of his composition, working with the existing structure of the courtyard to create a series of tableaux that are in dialogue with each other to create what I think of as a “juxtapositional narrative” – something I find myself referring to time and time again.

What led you to anarchist politics?

ER: I’ve always had a knee-jerk anti-authoritarianism that I’ve never fully grown out of (thank god). When I first encountered anarchism, it made immediate intuitive sense to me, primarily as a way of interrogating all the ways hierarchy and power operate in a given system/situation – and as a means to dismantle them.

I believe my first exposure to “serious” anarchism was reading Living My Life by Emma Goldman. I started considering myself an anarchist in a self-consciously anachronistic, nerdy teenager way.

Later, through a listing in the back of DisConnection magazine, I discovered the Trumbullplex, an anarchist housing collective in Detroit, which I moved into a year later.

I wax and wane in terms of my connection to or disillusionment with the anarchist scene, and having an ideological label to assign myself feels a lot less crucial to me as I get older. But the anarchist framework still makes the most sense to me.

Much of your work involves a laborious process of etching, scratching, and paper cutting. Can you say a little about your methods, materials, and why – aside from the stunning results – these methods are compelling for you?

ER: I am a real maximalist in terms of process. The more, the better. To paraphrase a friend of mine, sure I could use a computer instead of doing things by hand, but why would I want to spend less time thinking?

The majority of my print work involves at least one of two processes: either drawing out and then cutting images from paper with an X-Acto knife, or else an elaborate adaptation of scratchboard technique wherein I make a rough pencil drawing, lay a sheet of acetate over it, cover that in a messy ink drawing, then hatch that out, adding details and texture and refining lines. I usually go back and forth between these last two steps, revising and rethinking the imagery as it takes form. This is my favourite part.

These paper cuts or painted acetates are then used directly to expose silkscreens for printing, in lieu of the more customary photo transparency. I like this process because I like to work hard. I like to make things complicated/make complicated things because the world is such a complex and overwhelming place and the challenges we face are so deeply entangled with one another and seem, to me, to require a complex exploration and response.

I’m struck by a profound degree of empathy in your rendering of human figures, often in scenes of collective struggle or upheaval. How do your time-intensive methods factor in the emotional stakes of your prints?

ER: I feel like this question really hits the nail on the head in terms of what I aim for with my work. I think of my work as an extension of a long chain of empathy that begins with me as artist and first viewer. I feel an empathic connection to the figures in my work as I create them. As I draw their faces, I imagine their life and struggles and speculate on their relationship to the figures around them. Sometimes I fall a little in love with them. Sometimes they fall in love with each other.

My hope is that viewers who encounter the work will also share an empathetic response to the figures in my work and that this will expand their capacity for responding to people in a more deeply empathetic way. I feel like experiencing care for and connectedness with other human beings is a crucial beginning and through-line to creating social change. It is also something I personally struggle with, so I guess it provides me with some choice opportunities to conflate the personal with the political.

Tahrir Square (2012) by Erik Ruin; Silkscreen

In addition to printmaking, you’re a performance artist who does shadow puppetry in collaboration with musicians. What’s the relation between these more experimental forms and your explicitly political work?

ER: Well, there’s a very direct relationship in terms of materials! Much of the performance work I do these days is improvisational collaborations with musicians: from free-improvising violinists, to punk bands, to choirs. In these performances, I use the cuts and films I make for prints as raw material, manipulating them on the glass of multiple overhead projectors. Images that once had more direct meanings bend and break into bits of light and dark and colour, and move and meet each other in unexpected ways. I love this work in that it is immensely personally liberating and allows me to focus in on pure beauty in a way I rarely allow myself.

Erik Ruin. Photograph: Yoni Kroll

Meredith, you work in several media (musical, linguistic, visual) and also draw on experiences in different alternative communities, ranging from the Quakers to DIY subcultures. How have those social settings affected your art and your politics?

Meredith Stern: I was raised in a culturally Jewish household that honoured the importance of family and engagement in social justice work. My family was drawn to Quakerism and its belief in non-violence. I was incredibly inspired and influenced by the thriving community of international students at the Quaker boarding school I attended for high school. It was then that my two closest friends and I discovered the punk and DIY scene. It was the 1990s, and there was a really vibrant political punk scene in New York and Philly, and an amazing ’zine culture.

Since then, I’ve been a part of several creative spaces that have attempted to build a supportive community, or chosen family, and also recognized the need to shift our entire society through broader grassroots organizing. Over the years, the power of imagery and culture has become very clear to me.

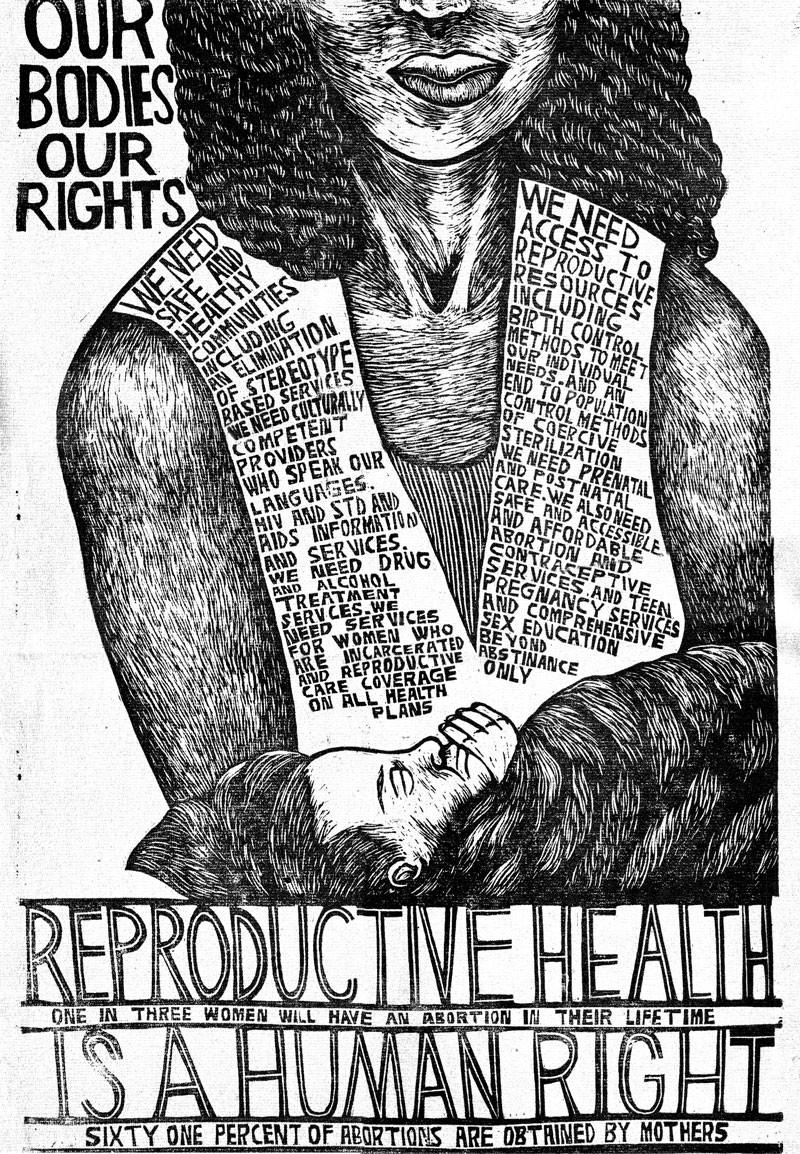

Our Bodies Our Rights by Meredith Stern; Linoleum block print

Some of your work is explicitly political and some is not. Do you experience any tension between the desire to create art or beauty and the desire and need to protest and foster resistance?

MS: I believe in order to create a more healthy society, we need to take care and find balance and love within ourselves. Anger and frustration are important emotions and can be strong forces toward improving our immediate circumstances, but I also think that working from a place of love and positivity can quickly and effectively draw people toward a movement and garner mass support.

I think it’s crucial for everyone, including social justice workers, to create spaces where we can feel joy and freedom to express ourselves. In order to create alternatives, we need to have places where we experiment, both mentally and physically, on what a liberated space might feel like. We need to both envision and build the world we want to live within.

Cat Self Portrait (detail) by Meredith Stern; Linoleum block print collage

On one hand, there’s an essentially romantic viewpoint that separates the realm of work or labour from creativity and art. At the same time, Madison Avenue and capitalist culture more broadly commodify and appropriate every domain of art in service to capitalism. How does the Justseeds co-operative model challenge both the romantic and the capitalist ties to creativity?

MS: I view all forms of skilled labour as forms of art. Capitalism tends to strip the romance away from our work. Many of us work jobs where we aren’t creatively or intellectually challenged, and our boss or co-workers may dehumanize us. I see the beautiful blend of art and utility working in unison in everything from carpentry to gardening. In my vision of a functional and healthy society, we are all employed in various co-operatively run enterprises where we are the workers and the owners, doing work that gives us joy. In such a healthy society we aren’t working more than 20 to 30 hours a week at these “jobs.” We also spend our lives baking bread with our neighbours and sharing child care responsibilities with our friends.

The Justseeds Artists’ Cooperative is a collectively run venture, so we all share in the responsibilities and rewards of being in the group. It’s empowering. And it’s an honour to be able to work with people in this way.

Meredith and Ozzy