In October, Catherine Tait, the CEO of the CBC, said in an interview that the CBC would no longer be working with Netflix to produce shows.

“Over time we start to see that we’re feeding the growth of Netflix, or we’re feeding the growth of Amazon, rather than feeding our own domestic business and industry,” she said. Earlier this year, Tait had likened Netflix’s role in Canada to “cultural imperialism,” a phrase that is rarely heard in Canada outside of media and communication studies departments at universities. The term is typically used to talk about a powerful nation imposing its culture on less powerful nations. Today, it mostly refers to the United States using its overwhelmingly dominant position in the capitalist global order to influence culture abroad – acknowledging that the United States’ cultural hegemony is part of the same project as its economic and military imperialism.

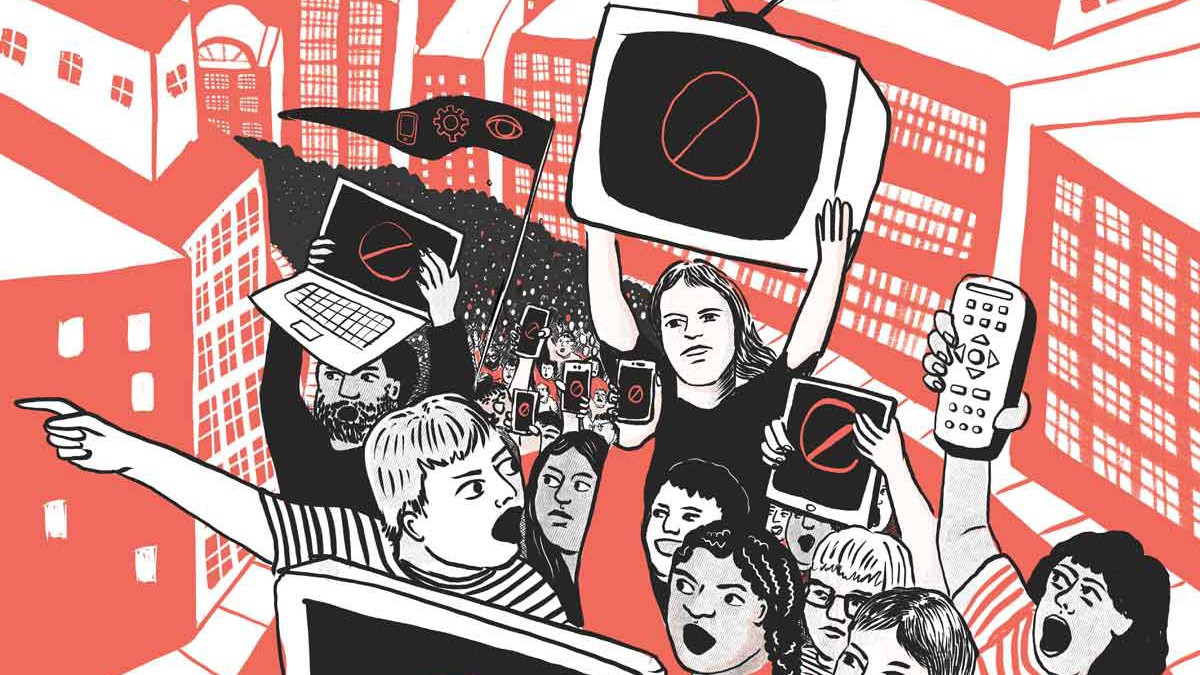

It’s not often that conversations about who should control Canadian media make it into the mainstream. We’re stuck in a catch-22 where, because of appalling levels of foreign ownership and corporate consolidation, there is little discussion of these dynamics in mainstream Canadian media. And while the left in Canada isn’t in a position to dictate new policies, Tait’s comments represent an opening into which the left can insert a radical proposal to change how we communicate with each other as well as how we create, distribute, and consume culture.

But getting to use something and having a meaningful say in its operation are two different things – and only one is really democratic.

While the recent rise of “platform capitalism” involves digital technology that connects many types of workers and consumers – like Uber, Airbnb, and WeWork – I specifically research the platforms that allow us to create and consume art and entertainment and to communicate with each other. It hardly needs to be emphasized how deeply these platforms – from Twitter to Netflix – are embedded in our everyday lives; how much of our creativity and how many of our ideas are held hostage by them. Many of these digital platforms rely on mountains of free content created by users – tweets, snaps, remixes, TikToks – while the platforms peddle the rhetoric that, by doing so, they are “democratizing” cultural production. But getting to use something and having a meaningful say in its operation are two different things – and only one is really democratic.

Control of these vital channels of communication is too important to be left to the capitalists and imperialists – both the U.S.-based ones like Netflix and Facebook and our local petty tyrants such as Bell or Rogers. We need democratic platforms and democratic cultural production. These platforms would put people before profit. That means proactive community regulation and decision making; a clear path for content creators to disseminate their work while making a living; and a serious commitment to many forms of meaningful cultural diversity. Ultimately – and I’m not the first to suggest it – this could mean putting platforms like Facebook in public hands by nationalizing them and making them co-operatively managed. And if, through nationalization, we begin to reckon with how inherently exploitative these platforms are, we may begin to consider rebuilding them from scratch.

When it comes to cultural production, who “wins”?

The problem of platforms and democratic cultural production in Canada is double-sided. On one side: production and ownership. On the other: distribution and consumption.

We cannot talk about platforms without talking about the political economy of the media industry as a whole, so I’ll begin by addressing how content is produced and subsidized. It’s also the key to understanding why the CEO of the CBC doesn’t want to work with Netflix anymore.

Canada is, without question, a massive producer of cultural commodities. According to Statistics Canada, 666,500 people in Canada worked in the cultural industries, contributing $53.1 billion to Canada’s GDP in 2017. Big-budget films (IT: Chapter Two, Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark), TV shows (Star Trek Discovery, The Boys), cutting-edge contemporary music (Jeremy Dutcher, Haviah Mighty), and digital games (FIFA 19, Watch Dogs: Legion) are made here, largely due to our skilled workforce and heavy government subsidies and loans for production. For example, in 2009, the Ontario government promised $263 million to Ubisoft to help fund the French video game multinational’s new studio in Toronto. This is on top of existing tax credits – like Ontario’s interactive digital media tax credit, which covers 40 per cent of expenditures for qualifying companies.

This means that Canada is a net exporter of cultural content: we ship it to the rest of the world, where it is consumed.

But do people in Canada own this content? Do we have much meaningful say over what is produced or the conditions under which it is created? For the most part, no. For example, while there are many more Canadian-owned game companies than foreign-owned game companies in Canada, the vast majority of game workers in Canada – 86 per cent – are employed by foreign-owned companies like Ubisoft or Electronic Arts. In film and television, too, foreign production outstrips domestic production.

This means that Canada is a net exporter of cultural content: we ship it to the rest of the world, where it is consumed. But the vast majority of profits collect outside the country, in the parent organizations’ regional offices. For instance, The Boys, while filmed in Toronto, is owned and distributed by Amazon, which will always collect the profits. Those profits are often then paid out as dividends to investors.

The rise of popular platforms like YouTube and Instagram – the majority of which are run by corporations based in Silicon Valley – has complicated and deepened historic patterns of media concentration. On one hand, research shows that there has been a flourishing of diverse content creators using these platforms to build new communities of production and consumption. Platforms are nominally open, and they give creators access to a worldwide market that can support a wide variety of demographic categories. It’s thanks to these platforms that left-wing podcasts have been flourishing in Canada: Alberta Advantage in Calgary, Dog Island in Halifax, or 49th Parahell in Montreal. These podcasts are able to eschew the corporate logic of media concentration in Toronto, and both Alberta Advantage and Dog Island are regional.

Platforms are nominally open, and they give creators access to a worldwide market that can support a wide variety of demographic categories.

At the same time, the vast majority of this diversity doesn’t “win” in economic terms on these platforms. A central belief of the “democratization of media” was that “anyone” (e.g., a working-class person with a great idea and a little bit of creative grit) could become a star because the gatekeepers could no longer keep them out. This has been proven to be false. For instance, the podcasts I mentioned above make very little money – they make $1,849, $209, and $439 a month via Patreon, respectively, at the time of printing. Instead we see the repetition of older dynamics – a small number of people and companies dominate the market and pull in the majority of ad and ancillary revenue while the rest languish in obscurity and economic precarity. In my own research with David Nieborg and Christopher Young at the University of Toronto, we found that the top 100 apps in the Canadian Apple App Store pull in 85 per cent of revenue. While the platform is relatively cheap to access, most app creators must fight for scraps – the remaining 15 per cent of revenue. Of all this revenue, of course, Apple also takes 30 per cent in transaction fees back to California.

Plus, these platforms have no obligation to be accountable to the people who use them. For years, platforms have been prohibiting some forms of speech (Tumblr’s banning of all content deemed “adult”) and amplifying others (the YouTube algorithm’s obsession with right-wing content or creepy videos for children). They give a megaphone to fascists and white supremacists, ignore reports of threats or abuse, then hide behind “freedom of speech” rhetoric when called out on it. And the real business model of the Google/Facebook duopoly, in particular, is the vast trove of users’ personal information that they collect and monetize. This data is often sold to other hoarders of digital data like Equifax, which subsequently lose it in public data breaches. Whether our data is deliberately sold to advertisers or unintentionally leaked, it’s not safe in the hands of unaccountable corporations which care more about their bottom line than our privacy.

Nationalize the platforms

A left-wing response to foreign ownership, however, isn’t just to prop up our own local cultural industrial monopolies. Facebook or Netflix wouldn’t be more virtuous if they were headquartered in Vancouver or Toronto. The Canadian government could certainly wield more power over them than they currently do (as evidenced by Facebook executives Sheryl Sandberg and Mark Zuckerberg’s ability to ignore a parliamentary subpoena earlier this year), but the general market dynamics that trend toward anticompetitive, anti-democratic concentration would still play out. According to the Canadian Media Concentration Research Project, Canada is the only country in the so-called “developed world” where all television – apart from the CBC and Netflix – is owned by telecom operators. It’s very clear that the problem of media concentration is created by a market that allows for the commodification of communications and culture. Systemic solutions will not be found in market mechanisms or incentives.

Instead, solutions will have to address both sides of the problem I’ve just laid out: production and ownership, as well as distribution and consumption. My focus in this piece on the role that platforms are playing in both areas of cultural production shows how they straddle the divide.

Facebook or Netflix wouldn’t be more virtuous if they were headquartered in Vancouver or Toronto.

At the level of infrastructure, Nikolas Barry-Shaw and the Courage coalition have laid out a detailed proposal, called “Communications for all,” which argues forcefully for the full nationalization of Canada’s telecommunications companies, putting them under federated, co-operative control. Saskatchewan’s SaskTel is an example of the benefits of such an approach: a public telecom company that maintains low prices and high-quality service in low-population areas. As for Internet infrastructure, there are numerous approaches, including the Labour Party’s promise of publicly owned, free high-speed broadband to every home in the United Kingdom by 2030. At the level of municipalities, Courage suggests Chattanooga, Tennessee as an example of a successful municipally-owned high-speed Internet infrastructure program.

Even if we concede that it’s not politically viable to fully nationalize the Canadian telecoms – which, given how incensed most Canadians are with being gouged on every phone bill, isn’t a defeat I’ll admit just yet – there are other proposals. For example, Dwayne Winseck, the project director on the Canadian Media Concentration Research Project, suggested that Canada Post merge with the CBC, creating the Canadian Communication Corporation (CCC), which would serve the combined functions of a national wireless and broadband Internet provider, and public broadcaster. Often in Canada, those who own the infrastructure play a role when it comes to funding the creation of content. Winseck proposes that the CCC would be able to fund public art and culture directly, thereby replacing our current “opaque labyrinth of intra- and inter-industry funds overseen by a fragmented cultural policy bureaucracy.”

Similarly, sovereignty over access to the Internet and control of their own means of producing, distributing, and consuming cultural content is key to democratic, decolonized platforms for Indigenous peoples. This work would build on the work of community-oriented media organizations like APTN, which already operates its own streaming portal, lumi, featuring Indigenous-produced and -owned content like the TV show Mohawk Girls.

At the level of platforms, there’s room for creative approaches, too. Courage, for instance, focuses on two issues: data protection and alternatives to the Silicon Valley giants. They suggest investing in public networks and decentralized social media solutions like diaspora or Scuttlebutt, which store data not on a huge central server, but on independently run servers across the world and on the user’s own device, respectively. Personally, I am a fan of Darius Kazemi’s project, Run your own social – a how-to guide on running a small social network site for 10 or 100 friends that uses existing infrastructure like the open-source, self-hosted social networking service Mastodon.

Sovereignty over access to the Internet and control of their own means of producing, distributing, and consuming cultural content is key to democratic, decolonized platforms for Indigenous peoples.

When I asked Fenwick McKelvey, who researches Internet governance and policy at Concordia University, to weigh in, he said he believes that the Canadian government needs to rethink what a public broadcaster could and should do. He proposes that the Canadian government buy Reddit, the discussion website that lets users vote on the text posts, links, and images that other users post. Reddit, which bills itself as the “front page of the internet,” serves a key function in the social media ecosystem – it’s a place where content is distributed, aggregated, and made discoverable. McKelvey’s idea echoes Evgeny Morozov’s recent proposal, in an article for the New Left Review, of “solidarity as discovery procedure” – using collaborative problem solving, instead of market dynamics, to discover solutions and information. The added bonus of Reddit being public would be that a public mandate could restrict intrusive advertising and other profit-seeking activities on the site. Plus, it would hopefully ensure that hate-speech laws would be enforced rigorously, rather than hoping that CEOs will finally wake up and realize that Nazis are indeed a problem.

In any of these scenarios, alternatives to the Silicon Valley giants will need to be creative for those who live outside the U.S., especially in the absence of the U.S. government directly breaking up or nationalizing U.S. companies like Facebook. And even if we do achieve nationalization, it won’t be a panacea. All of this comes with the broad demand of workplace democracy. We would need higher minimum wages, job guarantees, increases to existing social support programs, shorter workdays, secure employment, and strong unions to ensure dignified work for those who create culture and use platforms. Begging for Patreon donations isn’t a fair or sustainable model for funding cultural creation.

I have little faith that the Canadian state, in its current form, would choose to implement these solutions. We’ll have to exert enormous pressure from below, through a social movement that shows why, alongside so many other demands, everyone who lives in Canada deserves access and support to communicate with each other, build robust social ties, and create and share culture.

Regardless of the specifics, the keystone of a democratic platform is that the people who use it must control it. That will be the defining characteristic of the future Internet for people, not profit.