During the pandemic, I thought a lot about pain.

Mostly, I thought about traumatic pain: the pain caused by the million ways in which the pandemic – and governments’ responses to it – caused harm to people. The lives cut short and the missed funerals, postponed surgeries, and last rites.

But I also thought of physical pain. As my body readjusted to a state of pandemic hibernation, I had pain flare-ups due to a back condition that normally leaves me alone thanks to my physical activities, all stopped by pandemic measures.

My scoliosis is mild. When it causes me pain, I feel a sharp, stabbing pain in my lungs when I breathe and a dull ache in the upper part of my back. Mercifully, it goes away on its own, sometimes immediately, sometimes after several hours.

But lying down and feeling pain, evaluating pain and my relationship with it has been a regular routine of the pandemic. So when I picked up Carlyn Zwarenstein’s new book On Opium I was primed to dive right alongside her in her narrative non-fiction book where pain is the antagonist. Her specific kind of pain is also back pain, caused by ankylosing spondylitis. Unlike my short-term stabbing pain, hers feels, as she quotes from patient advocate Dawn Gibson, like “radioactive badgers and termites chewing on your bones.” But the book isn’t just about her own pain, it’s about pain more generally. She covers the gamut of kinds of pain – physical, social, psychological, spiritual – and the lengths to which people go to stop it.

If pain is the antagonist, opium is the protagonist, though perhaps calling opium the protagonist isn’t quite right. More like the anti-hero: a substance whose different origins she traces back throughout history and through to today to examine the various ways in which opium can be used to control and cause misery, but also to uplift and create pleasure.

Pain isn’t the only antagonist though. There are also abstinence and stigma, and the stubborn belief that living through pain is preferable to – or even more virtuous than – using opioids to manage it. It was this approach that defined Zwarenstein’s 30s – a decade where back pain controlled her life. She rationed her opium-derived Tramadol pills, trying to not “get hooked” as she tried to manage her pain.

If pain is the antagonist, opium is the protagonist, though perhaps calling opium the protagonist isn’t quite right. More like the anti-hero.

As the years progress, she recounts her first bout of withdrawal, taking it as a sign that perhaps she is more dependent on the drug than she had previously admitted. To finally address her pain, her dosage goes up and she discovers a life where she is freer to work, parent, and travel. She writes about how, gradually, through her friendships with other drug users and her journalism, she realizes that using opioids – whether for pain management, to suppress traumas, or even just for fun – isn’t in and of itself bad.

“I wish, now, that somebody had instead emphasized how badly pain can fuck up a perfectly good life,” she writes. “If I’d been less afraid and less moralistic about these drugs, I might have spent my thirties living rather than earnestly transcending suffering while trying to hold onto joy and love and life for myself and my loved ones. All this time, I didn’t have to suffer so badly.”

“The dichotomy isn’t between addiction and abstinence. It’s between chaos and stability,” and many people find that stability through opium-derived drugs, she concludes.

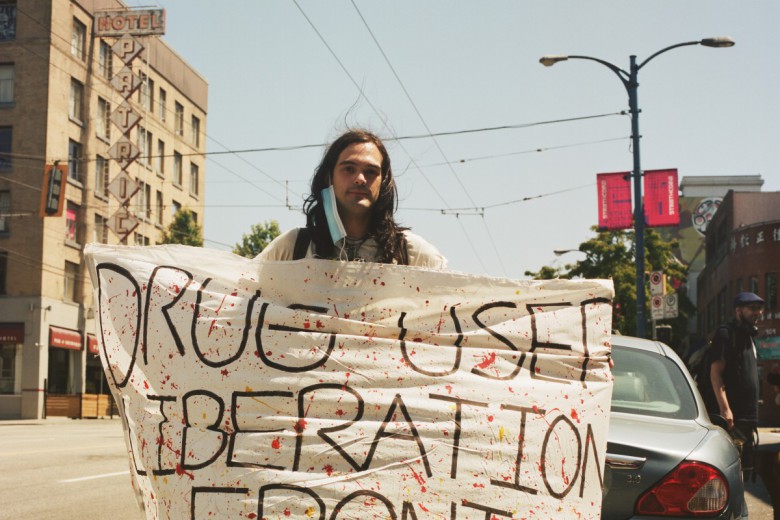

I’d like to call Zwarenstein a friend. We bonded over Twitter during the pandemic and I followed her Twitter updates as she was finishing On Opium this past year. Her book is full of stories of similar friendships: people she’s met in online pain forums and discussion groups, drug users and activists, doctors and other experts. She discusses the difficulty of navigating the imaginary line between these people being journalistic sources, fellow travellers, or friends. Their stories fill out the research on opioids and give a human face to the frenzied media coverage and political rhetoric that the so-called War on Drugs has delivered unto us.

Some of the characters Zwarenstein introduces us to die before the book ends. Others, we’re left rooting for, hoping that they avoid a batch of poisoned drugs, which has become an all-too-common conclusion to life in North America.

Zwarenstein has a very special and specific writing style. At times, it’s intoxicating. I felt swept into her world, whether on a trip to Venice or at a supervised injection facility. Then, she zooms out. Mixed in with the anecdotes and personal profiles of other opioid users is an incredible body of research that details alarming statistics: from overdoses to laws, from doctors who under-prescribe to the inhumane treatment drug users suffer just to get their medicine.

Though the current moment is one where everything feels like it’s urgent, the urgency in this book is transcendent. Some of the characters Zwarenstein introduces us to die before the book ends. Others, we’re left rooting for, hoping that they avoid a batch of poisoned drugs, which has become an all-too-common conclusion to life in North America. But the call to action is unmistakable: policies that criminalize and dehumanize drug users will continue to drive the opioid crisis.

She compares the United States to Portugal, world-famous for having decriminalized all drugs. As it introduced decriminalization, the country invested in other social supports to help drug users stabilize their lives. In 2020, more than 93,000 people died from drug overdose in the U.S. In Portugal, where the data is available up to 2019, the number of overdose deaths was 63. (Granted, the U.S.’s population is 32 times that of Portugal.)

The so-called War on Drugs is simply a war on people. More than four decades into the campaign, driven by a prohibition-at-all-costs sentiment, the human toll has been enormous, while drugs have become more dangerous. Zwarenstein puts drug users at the centre of this conversation, a location from which they are far too often pushed away, and forces us to reconsider everything we’ve ever thought about opioids.