On November 30, 2009, the Conservatives fired the opening salvo of a far-reaching assault against Canadian development non-governmental organizations (NGOs). The concerted campaign to shift the political centre of the NGO world began when the head office of KAIROS Canada received a phone call from the Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA) notifying the church-based development NGO that its request for funding had been rejected. CIDA officials cryptically informed the organization that its $7.1 million in federal funding had been cut because its activities did not fit the agency’s development priorities. It rapidly became clear, however, that KAIROS had run afoul of Stephen Harper’s foreign policy priorities, most notably his Conservative government’s staunchly pro-Israel stance.

NGOs guilty of similar transgressions soon faced cuts as well. In December 2009, Alternatives – another NGO critical of Israel’s occupation of Palestine – learned that its $2.1 million in CIDA funding would be cut. In April 2010, over a dozen groups concerned with women’s rights, including development NGOs such as MATCH International and the International Planned Parenthood Federation (IPPF), also suffered funding cuts. MATCH International ($400,000 in CIDA funding in 2009) and the IPPF ($6 million in 2009) had been critical of the Harper government’s anti-abortion stance internationally. For the targeted organizations, the loss of government funding meant between 40 per cent and 75 per cent of their annual budgets disappeared overnight. The cuts exacted a heavy toll: overseas programs were shut down, offices were closed, staff positions were eliminated, and properties were liquidated.

The spate of funding cuts was part of a broader effort to silence development NGOs. According to the Canadian Council for International Co-operation (CCIC), an umbrella group representing most of the major development NGOs in Canada, many NGOs received veiled warnings about taking positions that conflicted with Ottawa’s on issues such as climate change, free trade with Colombia, or the Middle East. “NGOs are being positively invited to remain silent on key questions of public policy,” explained then CCIC president and CEO Gerry Barr. The wave of cuts, Barr said, was “a messaging operation to the entire sector which essentially says, in billboard fashion, ‘Watch out what you say. You may pay a high price for it.’ ”

Fear rippled through Canada’s development NGO community. “In conversations that we have had with other NGOs, it has of course created a chill,” KAIROS’s now -retired executive director Mary Corkery reported. “There is fear of being in support of Palestinian people and groups, who essentially are struggling for land and livelihood.” When journalist Tim Groves asked Corkery which groups were feeling this pressure, she responded, “The chill is such that people don’t want to be named.” Several NGO leaders anonymously told the Globe and Mail that they had received subtle warnings from officials that the government disliked their public stances, but they were too frightened to speak out publicly. Shortly after the CCIC publicly complained that the government had created a “chill” in the NGO community by adopting “the politics of punishment … towards those whose public views run at cross purposes to the government,” it too had its three-year, $1.7 million CIDA grant cut.

The KAIROS cuts and their aftermath revealed uncomfortable truths about the relationship between the Canadian government and development NGOs. Contrary to their image as free-floating atoms of altruism, NGOs are actually tightly intertwined with the state. Over the years, NGOs’ coffers have been filled by ever-increasing amounts of public funding, which has produced organizations that are professionalized, bureaucratic, and dependent on a continued flow of government money. With the typical development NGO now reliant on federal funding for over 50 per cent of its annual budget, NGOs have steadily lost their institutional autonomy and are increasingly subject to the politics and priorities of the Canadian government. The government possesses “unusual life and death power over many Canadian NGOs,” former CBC journalist Brian Stewart remarked in the wake of the cuts. “In today’s Ottawa, all NGOs know a simple fact of life: displeasing the government means CIDA can turn off your NGO tap with ease, either by simply eliminating the flow or diverting it to another group that the government favours.”

Canada’s development NGOs, in other words, are not quite as non-governmental as they seem, and with politicians holding the purse strings, these NGOs face serious limits on what they can do and say. Harper’s cuts, however, did not provoke a sober reappraisal of the distortions and restrictions that accompany government funding. Instead, the cuts occasioned an attempt to breathe new life into old fantasies about Canadian benevolence and NGO independence.

Canadian exceptionalism

When it comes to international affairs, Canadians tend to believe in a kind of Canadian exceptionalism. While other western countries might have self-interested foreign policies and aid programs, Canada – and Canadian aid in particular – is somehow different. In particular, Canada’s traditions of quiet diplomacy and UN peacekeeping are often contrasted with the aggressive, arrogant, and self-interested foreign policy of the United States. Canadians overwhelmingly embrace such flattering characterizations of our international role. In June 2005, a Pew Global Attitudes Project survey of 16 western nations confirmed the widespread belief in Canadian exceptionalism: “Canadians stand out for their nearly universal belief (94%) that other nations have a positive view of Canada.”

To win public opinion to their side, leaders of the defunded NGOs appealed to this shining, Pearsonian vision of Canadian foreign policy. Specifically, the NGOs claimed that by cutting off funding to their organizations, the government was engaging in a dangerous politicization of CIDA, which had historically managed development aid in a disinterested, nonideological manner. “[I]f in fact the decision was a political one, then that is very disturbing for the integrity of Canadian aid,” Corkery told journalists after KAIROS lost its funding. Michel Lambert, executive director of Alternatives, made a similar point when he claimed the motives for the cuts were strictly “ideological” and had “nothing to do with development or humanitarian aid… It’s precisely to prevent humanitarian issues from becoming issues of foreign policy,” Lambert wrote in response to losing funding for his organization, “that the Canadian government created CIDA in 1968.” Canada was a global good guy, disinterested and fair in its dealings with the South – at least until Harper came to power.

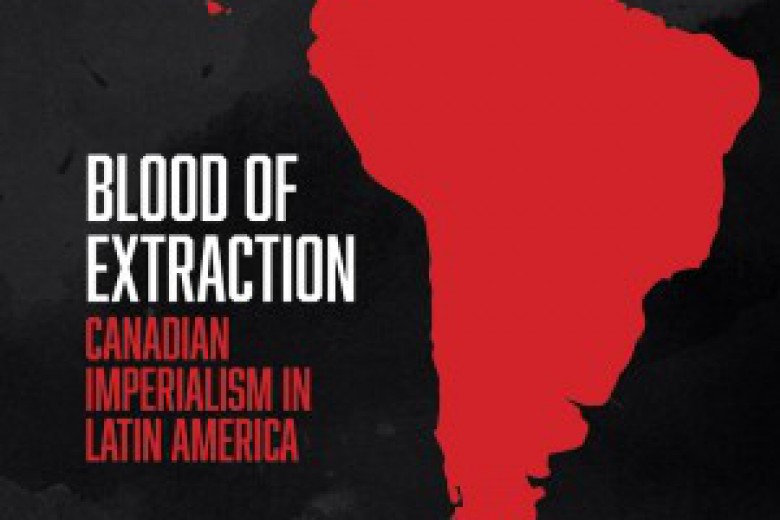

Yet, as political scientist Todd Gordon explains, this vision of Canada was never accurate. “Canada isn’t some mere middle power riding the coattails of our superpower neighbour … Canada has always had a self-interest to promote; Canadian capital has always had a controversial presence in the Third World, whether in banking in the Caribbean, manufacturing in apartheid South Africa or mining in General Suharto’s Indonesia. But the neo-liberal era, with heightened competition among multinational corporations and the aggressive market liberalization imposed on the Third World by the North (including Canada) has seen an unprecedented international expansion of Canadian capital.”

Canadian foreign policy is not exceptional, nor is Canada’s development aid program insulated from less-than-benevolent motives. Despite 40 years of justifying development aid on humanitarian grounds, writes Canadian foreign policy expert Cranford Pratt, “most scholarly commentators have concluded that humanitarian considerations have played little role within government in the shaping of those policies.” In one of the earliest studies on the subject, historian Keith Spicer described Canadian aid policies as designed “purely in the selfish interest of the state … Philanthropy is plainly no more than a fickle and confused policy stimulant, derived exclusively from the personal conscience. It is not an objective of government. Love for mankind is a virtue of the human heart, an emotion which can stir only individuals – never bureaucracies or institutions … Altruism as foreign policy is a misnomer, even if sometimes the fruits of policy are incidentally beneficial to foreigners.”

Quiet glories of a pre-Harper golden age?

In addition to betraying our historic international role as an even-handed diplomat and peacekeeper, the Harper government was accused of violating another hallowed Canadian tradition: respect for NGO independence. Lambert claimed the Harper government had disrupted the “symbiosis” between CIDA and development NGOs and pleaded for officials to recreate the “authentic partnerships” of the past, which had respected the independence of development NGOs. Michael Casey, executive director of Development and Peace, worried that the defunding of KAIROS and Alternatives threatened to disturb the “healthy environment of critique” that once existed between NGOs and the government. “This has always been encouraged in an open spirit of dialogue between government and civil society over the last 40-odd years.”

Political commentator Gerald Caplan argued that the “punishment politics” meted out against NGOs were a betrayal of quintessential Canadian values. “The issue here is the reversal, by Stephen Harper, of a 60-year consensus shared by all previous governments about the central role of civil society in Canada. Every previous government has funded civil society groups and NGOs even when they espoused policies that contradicted the government’s own. Governments might have done so grudgingly and not as generously as some of us hoped. But it has been one of the quiet glories of Canadian democracy that our governments have often backed groups that criticized them or had competing priorities.”

The accusations of his critics notwithstanding, Harper was in fact not breaking new ground. If anything, his Conservative government’s actions were in keeping with Canadian traditions. Liberal and Conservative governments alike have a long history of practising the “politics of punishment” against dissident NGOs. In 1975, the CCIC faced funding cuts after it criticized Canada’s position at the World Food Conference. In 1979, a radicalized Canadian University Service Overseas, the most prominent Canadian development NGO at the time, had its funding shut off completely. In the 1980s, NGOs supporting liberation movements of southern Africa and Central America were squeezed by CIDA. In 1991, the Inter-Church Fund for International Development, a precursor organization to KAIROS, faced CIDA’s wrath for its criticisms of structural adjustment. And in 1995, Canada’s national network of development education centres was effectively destroyed when CIDA slashed 100 per cent of its funding.

Neither the “60-year consensus” nor the “40-odd years” of government-NGO “dialogue” and “critique” ever took place. Ruling administrations of the past have disciplined NGOs that dared to contradict the government’s international stance, often just as ruthlessly as the Harper government. The Harper cuts were merely the latest example of Canadian governments using their power over CIDA funding to narrow the political space available to development NGOs. What was surprising was just how little the victimized NGOs did to draw the ire of the government. The left-leaning advocacy of KAIROS and Alternatives was meek in comparison to the militant, confrontational approach of the radicalized NGOs targeted by CIDA in the 1970s and 1980s.

The historical amnesia of the NGO leaders and their allies is politically convenient. There is little doubt that they know the history of past funding cuts, even as they promote the myth of a 60- or 40-year consensus at CIDA respecting the independence of NGOs. Hearkening back to a pre-Harper paradise lost allows the NGO leaders to maintain the pretense that their organizations were untainted by government influence until now. The decline of NGO independence may have accelerated under Harper, but the tendency has been playing out for decades. In Canada, as elsewhere, development NGOs have become increasingly integrated into the foreign policy apparatus. “While there was never was a golden age of NGOs,” writes Tina Wallace, “they are now becoming increasingly tied to global agendas and uniform ways of working.”

Blind spots

For years, aid critics have documented the ways in which CIDA has functioned to the benefit of Canadian multinationals while “perpetuating poverty” in the South. The role of development NGOs in this process, however, has never been systematically investigated. Due to their dependence on CIDA funds, development NGOs have become entangled in the foreign policy of the Canadian government, which is neither benevolent nor disinterested in its dealings with the Global South.

One of the most dangerous ideological effects of development NGOs is that they lead us to think about development in an apolitical way. Couched in rhetoric about “civil society,” “participation,” and “social capital,” NGOs often advance the notion that poverty and inequality can somehow be addressed independently of wider social and political structures. As anthropologist William F. Fisher argues, “Just as the ‘development apparatus’ has generally depoliticized the need for development through its practice of treating local conditions as ‘problems’ that required technical and not structural or political solutions, it now defines problems that can be addressed via the mechanisms of NGOs rather than through political solutions.”

Even more dangerous is the political blindness development NGOs can transmit about Canada’s actual relations with the Global South and about their own role within those relations. NGOs’ own inability to perceive these issues severely affects how they function. As veteran NGO worker Brian K. Murphy explains, “Ultimately, because they will be unable to make critical and politically aware choices, this limited vision will relegate the NGOs, at best, to a benign but marginal role in the world. At worst some will play a malignant role as agents of the very global social and economic forces that have created the conditions of poverty, deprivation, political repression, militarism, and environmental degradation experienced by billions throughout the world.”

It is the malignant role of NGOs that has come more and more into focus with the latest controversy over CIDA-NGO relations. In September 2011, CIDA announced it would be bankrolling Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) pacts between mining companies and three major NGOs (World Vision, World University Service of Canada, and Plan International) to the tune of $26.7 million. Months later, development NGOs calling for increased regulation of Canadian mining operations abroad, such as Development and Peace and the Mennonite Central Committee Canada, learned that their CIDA funding had been eliminated or severely reduced.

The CSR pacts were the subject of immediate criticism from local organizations. In Peru, World Vision Canada’s project with Barrick Gold was immediately denounced as a transparent attempt to stifle local resistance. Miguel Palacin, the general coordinator of the Andean Coordinator of Indigenous Organizations, wrote to World Vision Canada to decry their willingness to work with a company whose activities had already elicited strong opposition from farmers and indigenous peoples. “For this World Vision-led ‘development’ project to go ahead in the district of Quiruvilca in the face of concerted opposition locally and nationally would be tantamount to running a pacification program, and not a development project, in advance of the eventual destruction of a people’s way of life — all for gold.”

In recent years, the link between NGOs and pacification has become even more direct. In Afghanistan, NGOs have been swept up in the militarization of aid, with their projects increasingly shaped around the needs and interests of NATO’s counter-insurgency strategy. In Haiti, the complicity of Quebec’s NGO community in the bloody 2004 coup d’état has tarnished the reputation of organizations usually known for their progressive stances. Increasingly, NGOs serve as the human face of imperialism at home while mollifying opposition to Canadian geopolitical and economic interests abroad.

Thus, although the instrumentalization of NGOs in the service of Canadian mining corporations is particularly glaring, it is inscribed in a longer historical trend, one which was evident well before Harper came to power. Those seeking to build a more egalitarian world order and to express their solidarity with popular struggles in the Global South need to think about other organizational vehicles for their commitment. Internationalism is too important to be left to the NGOs.

This article is excerpted from Paved with Good Intentions: Canada’s Development NGOs from Idealism to Imperialism, released April 2012 by Fernwood Publishing fernwoodpublishing.ca