Population growth in southwestern Manitoba has been driven by immigration since the fur trade and accompanying colonization first began to displace the Cree, Sioux, and Anishinaabe in the 1700s. In the 1870s, British immigrants flocked to Manitoba and what was then the Northwest Territory to homestead the Prairie and clear the land for the agriculture that is associated with the area today. The arrival of the Canadian Pacific Railway in the early 1880s – and later the Canadian National Railway – saw the development of towns along the railway line, with grain elevators rising against the horizon at regular intervals.

Immigration to rural Manitoba continued apace up to the Second World War, with waves of immigrants arriving from eastern Europe. Ukrainian and Polish immigrants, as well as Mennonites and Hutterites fleeing persecution, settled into towns that were largely Anglocentric, often as second-class citizens, or created their own communities or colonies. First Nations and Métis people were relegated to reserves on land poorly suited for agriculture, or at the margins of society on the outskirts of town – on the “wrong side” of the CPR tracks.

Since the end of the Second World War, rural communities in southwestern Manitoba have been facing a demographic transition of a different sort. Technological innovation and a shifting world economy have made it easier to farm large sections of land with minimal human input, making it increasingly difficult for small family farms to compete. With less work in agriculture, people leave rural areas to work in larger urban centres.

At the same time, aggressive recruitment campaigns by the hog processing industry targeting would-be immigrants from Latin America, sub-Saharan Africa, and Southeast Asia are driving population growth in smaller urban centres and small towns in Manitoba.

The town of Neepawa and the city of Brandon are prime examples of how industry-driven immigration is rapidly changing the face of the once stereotypical Prairie town. Both communities were founded in the 1880s and thrived over the subsequent century. Over the past 30 years, however, their populations have aged significantly, and replacement birth levels languished.

Living high off the hog?

Neepawa and Brandon are now seeing tremendous population growth as a result of a new wave of immigration, and each has vacancy rates around 0.3 per cent. Both communities are home to large hog processing plants that recruit abroad to fill the bulk of their low-paying, difficult, and often emotionally disturbing positions. International workers are brought in on temporary foreign worker permits and promised “fast-tracked” immigration papers should they complete their contracts at the hog plants.

Starting wages for these unskilled, unionized positions are approximately $12 per hour – the same wages unskilled meat packers received in 1986, before the industry underwent aggressive restructuring. At that time, management won major concessions from the United Food and Commercial Workers (UFCW) union after crushing a series of high-profile strikes in Alberta meat-packing plants.

Maple Leaf Foods has benefited greatly from the Temporary Foreign Worker Program, through which the bulk of their current staff of 2,200 hourly workers are employed. For the workers themselves, the picture is less clear. Under the Temporary Foreign Worker Program, “there is always a constant threat of repatriation, of deportation, of not completing your requirements for residency,” argues Chris Ramsaroop of Justicia for Migrant Workers, a volunteer-run organization promoting the rights of migrant workers. As a result, workers are often reluctant to speak out in ways that might compromise their jobs or their applications for permanent residency.

Furthermore, workers are tied to their employer – in the case of Neepawa and Brandon, the HyLife and Maple Leaf hog plants – for years if they wish to remain in Canada. “There is no possibility for any real fundamental, meaningful justice from employer-driven programs,” Ramsaroop argues. “What we need to talk about is a transformation in policy, with [landed immigrant] status upon arrival.”

Workers at HyLife and Maple Leaf were not willing to speak on the record to Briarpatch about their experiences.

While newcomers to both Neepawa and Brandon are reinvigorating these towns with new life and energy, they also face challenges accessing basic services that long-time residents are very familiar with. How are Neepawa and Brandon welcoming their new residents, and in which areas are they falling short?

The Lily Capital

The town of Neepawa is home to over 4,000 people, approximately 10 per cent of whom are recent immigrants who moved to Neepawa to work at the HyLife hog processing plant since 2008. Incorporated in 1883, Neepawa has a high school and hospital, numerous businesses, and a junior level hockey team, regrettably named the “Natives,” that was recently the centre of a hazing scandal.

Neepawa is perhaps most famous as the birthplace of Margaret Laurence and the inspiration for the fictional town of Manawaka in which the bulk of her novels are set. Laurence’s Manawaka is a conservative, Anglo-Saxon town divided along lines of class and race. While this depiction did not make Laurence overly popular in Neepawa at the time she was writing and publishing The Stone Angel, The Fire-Dwellers, or The Diviners, today the historic Margaret Laurence Home is one of town’s main attractions. Laurence was buried in Riverside Cemetery in Neepawa after her death in 1987, not far from the stone angel that inspired her novel, and not far from where my grandparents, Roy and Stella Birnie, are now interred.

In 2008, HyLife Foods (then Hytek) purchased the Springhill hog processing plant, which had been owned and operated by local Hutterites. HyLife employs 550 hourly workers, over half of whom are Filipino, who process over 18,000 hogs a week.

When the HyLife plant opened in 2008, the first waves of migrant workers were Korean and Ukrainian. Many of these workers were highly skilled in other trades and chose to leave Neepawa to pursue opportunities outside of meat-packing – either in Brandon, Winnipeg, or out of province. Today, HyLife focuses on bringing trained meat packers from the Philippines to their Neepawa plant. Once HyLife has completed a $15 million upgrade to the plant in 2012, it will require a further 250 workers to process almost 27,000 hogs weekly. By the time the upgrades are functional and the workers and their families have relocated to Neepawa, it is estimated that over 25 per cent of Neepawa’s population will be of Filipino background, a dramatic increase from approximately one per cent four years ago.

“Housing is certainly first and foremost on everyone’s mind,” explains Marian Hijkoop of the Neepawa and Area Immigrant Settlement Services. Currently, Neepawa’s vacancy rate is hovering just above zero per cent, with the prices of single-family houses competing with those in Winnipeg, a city of 700,000.

The Wheat City

Brandon, Manitoba, is a city of approximately 43,000 people. As southwestern Manitoba’s trading centre, Brandon serves a total population of well over 180,000. Incorporated in 1882, Brandon has always been a hub of agricultural activity. Today, the city is home to a university, community college, and a Western Hockey League team, the Wheat Kings.

Brandon is also home to a Maple Leaf Foods hog processing plant. Opened in 1999, Maple Leaf’s Brandon facility now processes over 85,000 hogs a week and employs over 2,200 hourly workers, approximately two-thirds of whom are new immigrants. About 75 per cent of temporary foreign workers are fast-tracked to become permanent residents.

“The bulk of our growth is still driven by Maple Leaf,” explains Sandy Trudel, economic development officer for the city of Brandon. “We’ve got a variety of local businesses, whether they be manufacturers or other industries, that have gone out and hired newcomers from abroad as well because of their inability to fill those positions locally. But by far, the growth we’ve seen to date has been driven by Maple Leaf.”

Before Maple Leaf began hiring abroad in 2004, Brandon welcomed approximately 60 to 65 newcomers a year. Today, Brandon welcomes more than 10 times those numbers, with 600 to 700 new immigrants making their homes in Brandon annually.

“The community is booming,” says Sandra Carballo, settlement program coordinator with Westman Immigrant Services. “You can see it if you go on a Sunday afternoon to Superstore. It’s packed. It’s crowded, with people.”

Indeed, on a visit to Brandon’s Superstore on a Sunday, the crowd waiting for the doors to open at noon spills into the parking lot. Inside, you will hear Mandarin, Ukrainian, Spanish, French, and Amharic alongside English and Cree as you cruise through the aisles, which carry more diverse products than were available here 10 years ago.

Demand for services has increased with growth. “We’ve always provided some service to recent immigrants,” says Arlene Wachs of the Brandon Literacy Council, one organization providing literacy training and support. “But in direct response to the Maple Leaf recruitment, we doubled our client load. Our immigrant client load soon became about 50 per cent of our overall clients that we would serve in a year.”

There has also been a change in demand for how those services are provided. For many of Brandon’s newcomers, English is an additional language, and many have limited English literacy skills.

With high demand for services in languages other than English, the Brandon Regional Health Authority has begun offering interpretative services on site, “which is something that was unheard of before,” explains Trudel.

Still, many have trouble accessing services.

“A lot of families feel frustrated for not being able to communicate directly to the service providers,” explains Claudia Colocho. Colocho came to Brandon seven years ago from El Salvador to work at Maple Leaf. Today she works at Westman Immigrant Services and with UFCW in Brandon as a translator. “Others decide not to access this service because of the cost of it.”

Changing Prairie towns

The growth in both Neepawa and Brandon is in direct contrast to the decline that many rural communities across the Prairies are facing today. Communities in southwestern Manitoba are losing basic services needed to keep and grow a population, like facilities for education and health care. However, Neepawa and Brandon’s growth is spurred by a single industry that is driven by volatile international market demands. A downturn in pork exports could prove disastrous to both communities.

Much like today’s newcomers, my ancestors came to Canada to work at jobs that were low paying and unpopular among those Canadians who were already established in the country at that time – namely, agriculture. But when my ancestor John Birnie came to the area north of Neepawa in the 1870s, European settlers were given land in exchange for their labour, a far cry from the “fast-tracked” immigration papers and no guarantee of affordable housing that immigrant workers receive, at best, today.

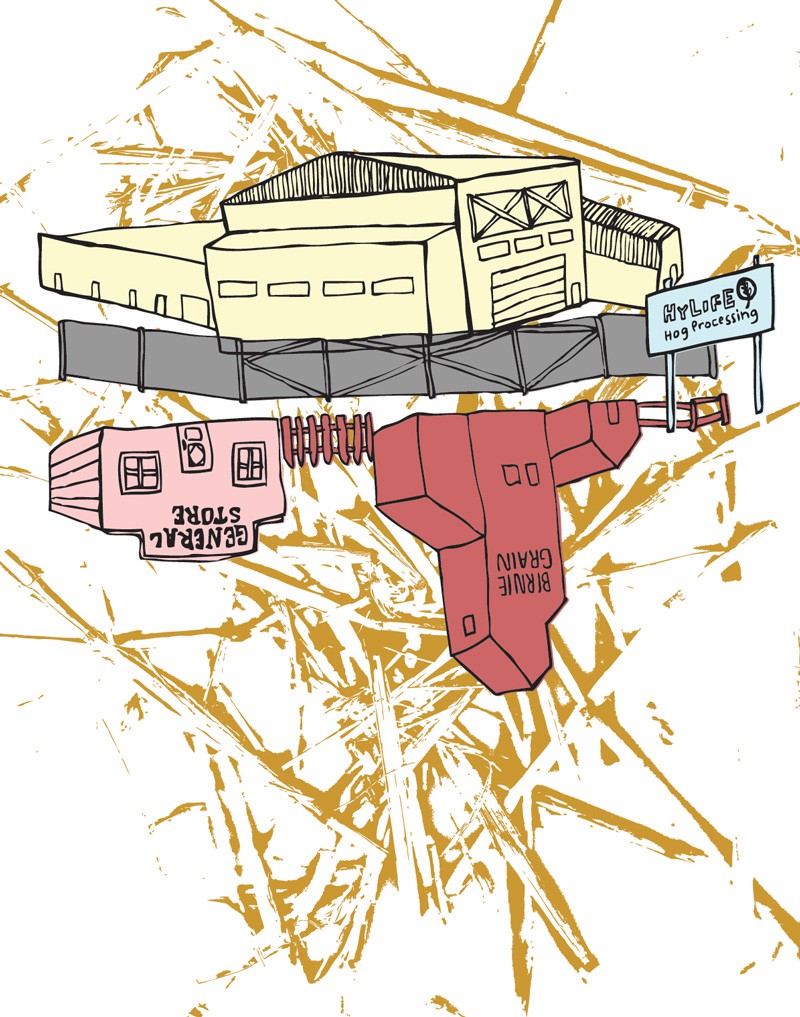

The land that John Birnie and his family homesteaded, originally Anishinaabe territory, eventually became the village of Birnie. At its peak in the 1930s, Birnie was home to almost 300 people and three grain elevators. Today, the “town” consists of two sparsely populated blocks, a community centre, a row of post office boxes, and a population of approximately 60. Like many rural communities in Manitoba today, the elevators, the church, and general stores are all gone. The closest school is in Eden, which, as Marian Hijkoop explains, can expect to see an increase in enrolment numbers for the first time in decades because of growth in nearby Neepawa.

While the numbers indicate positive economic and social outcomes as a result of immigration-driven growth, what often goes unreported is the day-to-day life of new immigrants and the challenges they face when relocating to a community that is, for the most part, culturally homogeneous. Historically, Brandon and Neepawa fit that description. Ten or 20 years ago, either could pass as the quintessential largely white, English-speaking Prairie town. While both communities owe their existence to immigration policies encouraging settlement for the bulk of their histories, the cultural and social discourse has been Anglo-normative. As populations in both communities continue to divers-ify, those preconceptions are on their way out the door.