Despite much ado over the world’s dwindling oil supplies, the real lifeblood of the planet is water—and we are quickly draining the well dry.

Drinkable fresh water accounts for less than one-half of one per cent of all of the earth’s water. With global water consumption doubling every 20 years, the United Nations projects that the demand for water will rise 56 per cent above available supply as soon as 2025.

As Maude Barlow and Tony Clarke point out in a 2002 article in The Nation, “the world is running out of fresh water. Humanity is polluting, diverting and depleting the wellspring of life at a startling rate. With every passing day, our demand for fresh water outpaces its availability, and thousands more people are put at risk.” As the situation worsens, powerful transnational corporations are stepping in to influence the debate and propose profitable, privately delivered solutions. Already, just two French companies—Suez Lyonnaise des Eaux and Vivendi SA—control the distribution of water to almost 100 million people in over 120 countries. Such companies see water scarcity as a lucrative business opportunity and the market as the best mechanism for allocating water resources. Given that fresh water is essential for human survival, these companies recognize that people will pay whatever they can to get it.

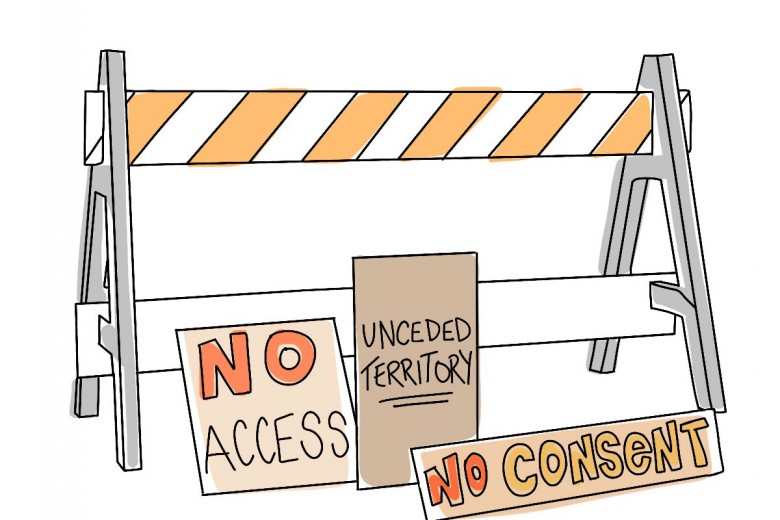

But citizen groups around the world, fed up with corporate control of this vital resource, are fighting back. From the Congo to Canada, Ecuador to England, people are resisting the privatization of water and struggling to have access to clean water enshrined in law as a human right, too important to be handed to for-profit companies to distribute according to people’s ability to pay.

Ashfaq Khalfan, coordinator of the Right to Water Programme at the Centre on Housing Rights and Evictions in Geneva, argues that approaching water as a human right can provide an important foundation for holding governments and other actors accountable for water service provision. “It provides those lacking access to water with new institutional recourses, such as courts and commissions, as well as the possibility of support from the human rights movement.” Indeed, recognizing the human right to water has become a rallying cry for a global movement.

In their 2002 book Blue Gold: The fight to stop the corporate theft of the world’s water, Maude Barlow and Tony Clarke show how the current ambiguity over a state’s obligations to ensure access to fresh water for its citizens has allowed many governments and international institutions to push through privatization deals in the face of freshwater shortages. This is in part made possible by the fact that water is seen by the World Bank as a “human need” rather than a “human right.” As Barlow and Clarke emphasize, “These are not semantics; the difference in interpretation is crucial… A human need can be supplied many ways, especially for those with money. No one can sell a human right.”

The World Water Council reports that 1.1 billion people currently live without access to clean drinking water. Meanwhile, Fortune Magazine estimates annual revenues of the water industry to be over US $400 billion—a third higher than those of the pharmaceutical industry.

As the global water shortage fast approaches a level of crisis, the momentum to have water recognized as a human right is growing. At the 2006 World Water Forum, Bolivia’s water secretary, Abel Mamani, led a push to have water declared a fundamental human right in the forum’s final statement. The effort was quickly suppressed, however. “The right of water is not relevant to this forum,” declared Jamal Shakir, director of the World Bank’s Energy and Water Department. Significantly, the forum was organized by the World Water Council. Forty per cent of the Council’s membership are for-profit companies with stakes in water privatization.

For water activists, Bolivia stands as a beacon of hope in the struggle to maintain—or regain—public control of water. In 1999, a corporate consortium led by U.S. corporation Bechtel signed a 40-year contract to deliver water supplies and services to Cochabamba, Bolivia’s third-largest city. Bechtel proceeded to raise the price of tap water as much as 200 per cent, and began exporting Bolivia’s water in bottles to Europe. Within six months, a grassroots popular uprising in Cochabamba succeeded in chasing Bechtel out of the country. To this day, Cochabambans retain community control of their water.

Hamilton, Ontario, recently conducted its own experiment with municipal water privatization and learned of the disastrous consequences the hard way. In 1994, Philip Utilities Management Corporation was awarded an untendered contract to run the city’s waterworks and sewage treatment operations. What followed, according to Canadian Union of Public Employees President Paul Moist, was “a workforce slashed in half within 18 months, a spill of 180 million litres of raw sewage into the harbour, the flooding of 200 homes and businesses, and major additional costs.” In 2004, the city abandoned the experiment and decided to bring water back into the public sector.

One might hope that Canada would join with Bolivia, Venezuela, Cuba, and other nations in the struggle to protect water as a fundamental human right, but the opposite has been the case. In 2002, Canada stood alone at a meeting of the UN Human Rights Commission as the sole dissenting voice opposing a motion affirming the right to drinking water and sanitation, stating, “Canada does not accept that there is a right to drinking water and sanitation.” Stephen Harper has ignored repeated calls to clarify Canada’s position with regard to the right to water.

Universal access to clean drinking water would potentially save governments billions of dollars a year, argues a Friends of the Earth report, Nature for Sale: The Impacts of Privatizing Water and Biodiversity. The report estimates that access to clean water would save $125 billion annually in direct medical expenses and other costs linked to preventable water-related diseases.

So why do western governments oppose the right to water and favour water privatization? Put simply, water privatization is extremely profitable for the companies that land the contracts, and governments in thrall of the neo-liberal consensus are convinced that private companies can deliver resources more “efficiently” by off-loading the costs onto individuals.

Canadian public opinion, however, is firmly on the side of the right-to-water movement. According to a 2004 Ipsos Reid poll, 97 per cent of Canadians surveyed believe that “Canada should adopt a comprehensive national water policy that recognizes clean drinking water as a basic human right.” Furthermore, 183 municipal governments across Canada have passed resolutions affirming that access to clean water is a basic human right.

At the 2006 World Water Forum, the governments of Bolivia, Cuba, Venezuela and Uruguay refused to sign the event’s final declaration because it failed to exempt water from trade agreements and did not endorse the right to water. Canada sided with countries favouring the commodification of water.

In 2007, at the UN Human Rights Council, the High Commissioner for Human Rights, Canadian Louise Arbour presented a report calling for stronger regulations governing water companies, including penalties for corporations that restrict people’s right to water. Water rights activists and concerned citizens alike continue to urge the Government of Canada to reverse its shameful position of opposing the human right to water at the United Nations, however to date no reversal has been announced.

Now see if these figures float your boat . . .

Freshwater lakes and rivers, ice and snow, and underground aquifers hold only 2.5 per cent of the world’s water. By comparison, saltwater oceans and seas contain 97.5 per cent of the world’s water supply.

Fifty percent of the world’s wetlands have been lost since 1900.

As part of the Millennium Development Goals, UN member states pledged to reduce by half the proportion of people without sustainable access to safe drinking water by 2015.

Every year, 1.8 million people die from diarrheal diseases (including cholera); 90 per cent are children under five, mostly in the Global South.

Worldwide, one billion people lack access to safe drinking water, while 2.4 billion lack access to adequate sanitation.

One drop of oil can render up to 25 litres of water unfit for drinking.

Health problems related to water pollution in general are estimated to cost Canadians $300 million per year.

You can survive about a month without food, but only five to seven days without water.

Approximately 1,000 kilograms of water is required to grow one kilogram of potatoes.

The Great Lakes are the largest system of fresh, surface water on earth, containing roughly 18 per cent of the world supply.

The Great Lakes support 33 million people, including nine million Canadians and eight of Canada’s 20 largest cities.

Only one per cent of the waters of the Great Lakes are renewed each year by snow melt and rain.

Source: Environment Canada