Like many Canadians and most who identify as leftists, I grew up thinking about the world the way a social democrat would, even if I didn’t know what the term meant. I believed in a robust public sector including all health care and education, steep taxation, tough environmental regulations, strong labour laws, a livable minimum wage, and palatial public libraries. It all seemed rational, humane, and workable.

As such policies and institutions came under attack, and my political education progressed, I realized one of the most important words in the world wasn’t used in classrooms or the media: capitalism. I’d inherited my social-democratic worldview from my parents’ generation, who entered adulthood in the unprecedented economic expansion after World War II. My parents rose from rural poverty and entered the urban middle class (as school teachers) on the industrial tide of the postwar boom. As that boom went bust in a series of economic crises in the 1970s, the “common sense” of social democracy dissipated and the political left weakened.

For social democrats the goal is to constrain capitalism, to manage it. It’s why people denounce “unfettered” capitalism but not capitalism itself. The trouble with taming capitalism, however, is that capital has a way of bursting its fetters. As Marx and Engels put it, “The need of a constantly expanding market for its products chases the bourgeoisie over the entire surface of the globe. It must nestle everywhere, settle everywhere, establish connections everywhere.” Capitalism’s need for endless growth brooks no earthly limitations.

Throughout my life, the basic assumptions of conscientious Canadians have thus taken a pounding. Instead of incremental progress and social advance, the last 35 years have seen escalating inequality and a terrifying climate emergency immune to the environmental movement’s ambitions. The social democratic dream of a well-regulated “mixed economy” has taken a nightmarish turn.

As the neoliberal era drags on, people committed to some version of humane capitalism have begun to move through the five stages of grieving: some are in denial, some are angry, some are simply depressed, but very few can accept the demise of social democracy. Many seem to be at the bargaining stage (which precedes depression). They cling to individual figures of perceived integrity like Jack Layton; they hope local gardens and co-ops might lead to a democratic economy; they see Stephen Harper as the root of all evil, not an all-Canadian boy who emerged predictably from a capitalist society founded in settler colonialism.

Reality is mean. For younger generations, the world has been getting worse in serious ways all our lives. We have grown up in an age of privatization, deregulation, debt, shitty jobs, and ecological ruin. Little wonder that depression has become the “common cold” of mental illnesses.

Yet, paradoxically, we’ve also been blessed with a better society than our parents. I grew up with dramatically less constrained models of masculinity, gender, and sexuality than did my father. Feminists have made profound and inspired gains every single year of our lives: it was only in 1983 that spousal rape became a criminal offense in Canada. Lesbian, gay, and queer activists have remade our world. Indigenous Peoples have challenged the settler state relentlessly. Migrants and people of colour have whittled away at Canada’s default white supremacy year after year.

Such struggles against humiliation and oppression are also always struggles for a new world. A world with less hardship and fewer indignities. An emancipated society in which we could be different without fear. This issue of Briarpatch was put together without a guiding theme, but if there is a red thread running through its pages it is dignity.

Dignity is irreducible. It is hard to pinpoint, tough to distill, because it is interrelational and social. We are stirred, called to each other, because we all enter the world touched, dependent on love, hungry for more than food.

Systems of indignity take different names and forms – wage labour, patriarchy, white supremacy – but they all make us ill. We cannot abide them even if their power seems ascendant and no clear strategy of refusal is at hand.

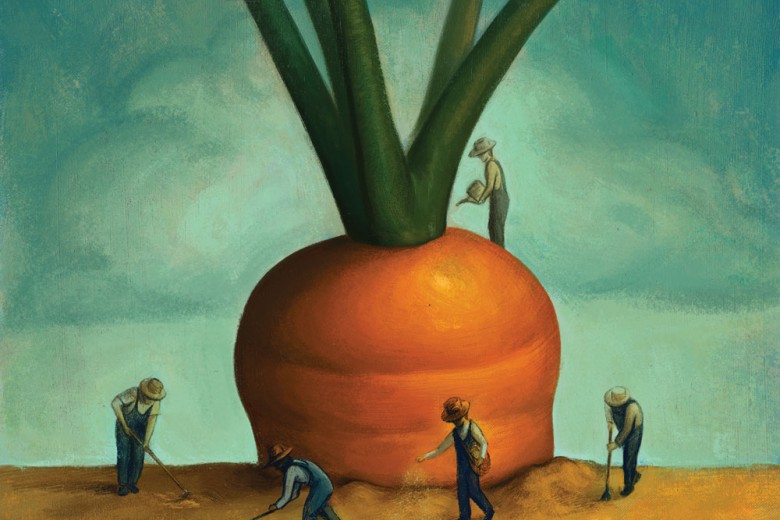

Dignity is, ultimately, why we are on the political left. It is connected to the energy by which we can reckon with domination rather than crumple in its grasp. It is why we have each other. This issue is devoted to the dignity of prisoners, the dignity of low-income people, the dignity of farmers, the dignity of our kids, and the dignity of young women who move through a world that can seem too hostile to bear.