A 21st-century land rush is sweeping the globe. Amid skyrocketing food prices, climate-related instability, and declining soil and water resources, wealthy investors have begun to size up the world’s farmland as both an investment opportunity and a hedge against food crises and political turbulence. Players in this global land grab include individual, institutional, and corporate investors, as well as governments. And although estimates vary widely, large-scale land deals have seen at least 71 million hectares change hands since 2000.

For many investors, farmland acquisition – either through purchase or lease – offers a chance to profit from rising agricultural commodity prices. Such investors take a direct hand in farm production, typically on large plantation-like operations, with an eye to profiting from high prices for food, fibre, and biofuel crops. Rising food prices have also encouraged governments of countries such as Saudi Arabia, South Korea, and Egypt to lease huge tracts of land, mostly in Africa, as a means of securing food for their own populations. Producing food offshore allows capital-rich but land-poor countries to bypass volatile global food markets and guard against food riots and related political instability.

Still other investors buy farmland as a form of speculative investment in rising global land prices. By renting the land to individual or corporate farmers, investors gain a regular income stream on top of appreciating land values. These investors also acquire farmland as a low-risk hedge against inflation and other side effects of the global financial crisis. As with the rush to buy gold, farmland investment is seen as a safe harbour in stormy financial seas.

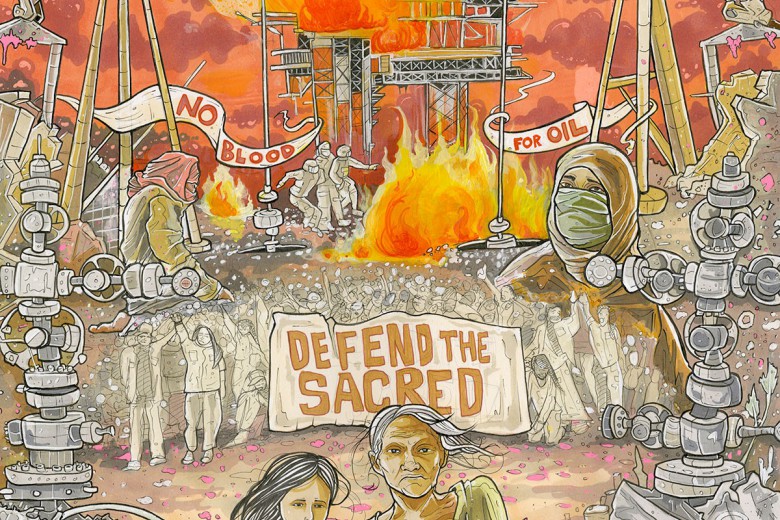

The global land rush has attracted considerable attention from the media, civil society, international development agencies, and governments. While some welcome these developments as a source of much-needed investment in global agriculture and a way to bring new infrastructure, technological improvements, and jobs to target countries, critics have denounced the deals as resource grabs that dispossess small-scale farmers and Indigenous peoples, threaten food sovereignty, and further degrade agro-ecosystems. These concerns are compounded by the fact that the mechanisms by which these deals are negotiated, monitored, and enforced have been murky at best.

To date, debates around farmland acquisition have focused mostly on how the phenomenon is playing out in the Global South. Much less attention has been paid to large-scale acquisitions of farmland in wealthier countries like Canada. Yet investment analysts have highlighted Canadian farmland as a prime investment opportunity given the country’s huge arable land base, high-quality soil and water resources, well-developed infrastructure, and political stability. Saskatchewan’s farmland has gained a particularly noteworthy reputation, making the province a global hot spot for farmland investment.

Saskatchewan farmland in the crosshairs

With more than 64 million acres of arable land, Saskatchewan contains almost 40 per cent of the farmland in Canada – more than any other province. Yet it is not only the quantity of farmland in Saskatchewan that attracts investors but also its quality. Investment analysts stress that the province contains some of the world’s finest grain lands, with productive soils and reliable access to water. Under the mild climate-warming scenario predicted for the Prairie region, Saskatchewan’s agricultural productivity is expected to rise.

Saskatchewan’s proximity to major North American markets, together with its strong processing and transportation infrastructure, are also key considerations for farmland investors. Stable political and legal systems at both the provincial and federal level offer more security than many of the other countries that have attracted significant investment dollars.

On top of these factors, many analysts consider Saskatchewan farmland to be undervalued, making it all the more appealing. Saskatchewan farmland is not only cheaper than similarly productive land in neighbouring provinces and states, it also compares well with farmland costs overseas. The Knight Frank International Farmland Index, which measures farmland values around the world, recently pegged the average cost of farmland in Saskatchewan at $526 per acre, a bargain compared to prices in places like Brazil, the U.S., and the U.K.

Saskatchewan farmland prices are rising, however. Farm Credit Canada reports that farmland values in the province have risen steadily since 2002, increasing a total of 81 per cent over the past decade. The largest gains occurred in the latter half of 2008 and first half of 2011 when peak global commodity prices spurred increased demand for farmland and led to average value increases of 8.8 per cent and 11.6 per cent, respectively.

Some see the recent appreciation of Saskatchewan farmland as the market “catching up” after having been artificially depressed by restrictive ownership laws. In 2002, the NDP government lifted restrictions on farmland ownership by non-Saskatchewan residents, opening up ownership to any Canadian citizen or business with all-Canadian investors (except for publicly traded corporations) and harmonizing Saskatchewan’s landownership laws with those of Alberta and Manitoba. All three provinces still prohibit foreign ownership of all but small tracts of farmland, and Saskatchewan and Manitoba also prohibit leasing by foreign interests, but many farmland investors would like to see these regulations changed. Indeed, many investors may be counting on further liberalization of farmland markets in their investment forecasts.

But if strong returns on Saskatchewan farmland have helped to fuel its rising status as a star commodity, this is only half of the equation. The other half is the low volatility associated with farmland investments, something that is particularly attractive given the recent turmoil in Canadian and global financial markets. A recent analysis showed that, compared to a fall of 37 per cent in the Toronto Stock Exchange (TSX) composite index during the 2007 to 2008 subprime crisis, Canadian farmland values rose by 10 per cent during the same period. Similarly, while the current European debt crisis has pushed markets off by as much as 13 per cent, Canadian farmland continues to appreciate at seven per cent. These figures highlight the superior hedging power of Canadian farmland and demonstrate a risk-return profile unmatched by other investments.

High food prices and forecasts of future food crises have made Saskatchewan farmland all the more appealing. Farmland investors point out that with a growing population and a fixed amount of farmland, arable land per capita is in decline. In the meantime, growing global demand for meat and dairy is exacerbating pressure on food-producing resources. These conditions help to explain both the keen interest in Saskatchewan farmland and the emergence of two new mechanisms through which investors can gain access to it: farmland investment funds and One Earth Farms.

Farmland investment funds

Farmland investment funds (or trusts) are specialized funds that pool investors’ money to acquire a large portfolio of farmland across a wide geographic region that is diversified by soil type, climate, and type of production, among other factors.

Farmland investment funds and the firms that administer them are relatively new to the Prairies. The past decade has seen the emergence of three main firms. Two of these – Regina-based Assiniboia Farmland Limited Partnership and Calgary-based Agcapita – were started in 2005, and each focuses exclusively on Prairie farmland, mostly in Saskatchewan. The third – Bonnefield, a 2010 start-up based in Toronto – is developing a broader Canada-wide portfolio that includes Prairie farmland.

Farmland investment funds raise their capital by selling units to participating investors based on a minimum investment ranging from $10,000 to $150,000. The fund managers then acquire farmland that meets their criteria with respect to price, yield potential, location, and other factors. In order to comply with provincial landownership regulations, the funds are structured as private partnerships, as opposed to public companies whose shares could be sold on a stock market, and participants must be Canadian citizens or permanent residents.

To date, Assiniboia, Agcapita, and Bonnefield have acquired about 157,000 acres (64,000 hectares) of Prairie farmland. In the fall of 2011, Assiniboia and Agcapita were each raising money for a new round of land acquisition, worth $20 million apiece. This will bring the total invested by these specialized funds to somewhere in the neighbourhood of $200 million over the last five or six years.

To date, farmland investment funds have shown little interest in directly participating in farm production. Instead, they rent the land they acquire to existing farmers – in some cases, the very farmers who sold them the land in the first place.

Part of the appeal of the funds is that the rent payments provide a regular revenue stream, even while the portfolios increase in value as farmland prices rise. Assiniboia, for instance, reported a 30 per cent increase in the net asset value of its units for 2011. Farmland investment funds may also have other income streams such as oil and gas surface leases, the sale of carbon credits, and sales or shares of the crops produced by contract farmers.

All of the farmland investment funds take great care to select tenants with a shared farming philosophy: a desire to maximize production with the most advanced agrotechnologies and a propensity for very large-scale operations. Each company also reinforces this philosophy through a farmland management side of their business, which is variably responsible for selecting tenants, managing leases, monitoring farming practices, and providing production advice to tenant farmers.

One Earth Farms

One Earth Farms is a new corporate farming venture launched in 2009 by Sprott Resource Corp., a publicly traded natural resource sector investment firm. Headquartered in Toronto and traded on the TSX, Sprott has a diversified portfolio of mining, oil and gas, and agricultural development projects, as well as sizable gold bullion holdings.

One Earth Farms believes that its unique business model – a large-scale, integrated farming operation spread across the Prairie provinces – will produce healthy financial returns. Unlike the farmland investment funds profiled above, One Earth Farms is directly involved in food production, growing grains, oilseeds, and specialty crops, and raising range-fed cattle.

The company has grown rapidly over its first three years to encompass more than 190,000 acres (76,900 hectares) of cropland and pasture in southern Saskatchewan and Alberta. Sprott suggests that One Earth Farms is now the largest farm in Canada, and is well on the way to its goal of farming 1 million acres by 2015.

The capital for One Earth Farms’ dramatic expansion has come from Sprott itself and from outside investors. To date, Sprott has invested a total of $57.5 million in the venture and retains 58 per cent ownership of One Earth Farms. Outside investors, including agribusiness firms Viterra, Ag Growth International, and Alliance Grain Traders, have contributed $54.5 million to the project.

One Earth Farms differs from the farmland investment funds in that the company relies on leased land for its operation. Currently, most of the company’s farmland is leased from First Nations. Farming on First Nations’ reserves, which are federally regulated, allows Sprott to circumvent provincial landownership restrictions prohibiting publicly traded companies from establishing large-scale farming operations on the Prairies.

One Earth Farms describes its relationship with First Nations as a “true partnership,” in which the company provides bands with lease revenues, training and employment opportunities, and equity in company subsidiaries. These benefits have led to agreements with 11 First Nations to date, including the Blood Tribe in Alberta and the Muskowekwan, Little Black Bear, Thunderchild, Star Blanket, Yellow Quill, Cote, Keesekoose, Fishing Lake, Kawacatoose, and Chacachas First Nations in Saskatchewan.

Despite its ambitious goals, One Earth Farms has yet to turn a profit. Sprott’s audited financial statements indicate that the company lost $11.9 million on One Earth Farms’ operations in 2010 and $3.2 million in 2009. This can in part be explained by the venture’s significant start-up costs as well as the excess moisture conditions on the Prairies in 2010 and 2011, which limited production.

Whether One Earth Farms will recoup these early losses remains an open question. The company’s unique scale and business model is virtually untested on the Prairies, and it is unclear whether it will be able to generate significant profits – especially in the event that high commodity prices begin to fall.

For Sprott and its co-investors, the ultimate profit will be determined at the company’s exit from the venture. Sprott plans to eventually take One Earth Farms public or sell it to another investor, such as a pension fund or sovereign wealth fund. The price that One Earth Farms garners at that point will depend partly on the value investors place on the company’s access to farmland.

A new paradigm for Prairie farming

Together, the new farmland investment funds and One Earth Farms point to important changes to the face of farming on the Prairies. Most obviously, these investments contribute to the accelerating concentration of the ownership and utilization of farming resources. Although the trend towards ever-bigger farms is a long-standing one, the landholdings involved in the farmland investment funds and One Earth Farms are on another order of magnitude altogether.

Quite apart from their scale, farmland investment funds and One Earth Farms also represent new instruments by which outside investment capital is applied to Saskatchewan farmland and farming. While banks have long played a central role in the farming sector through the provision of credit, farmland investment funds and One Earth Farms demonstrate the growing interest in farmland and farming among individual and corporate investors.

In this sense, the emergence of these new initiatives represents something of a paradigm shift for farming on the Prairies. The growing influence of more socially and spatially distant actors in the sector raises the question of who will reap the rewards and who will bear the risks associated with the transformation of the global agri-food economy. Although agricultural commodity prices are high and farmland values are rising, Prairie farmers know that the good times rarely last. These new models may well prove less resilient than traditional family farming when it comes to surviving the lean years and coping with constant change.

These new forms of investment also have special implications for the link between landownership and farming. For one, landownership has always been a central part of our understanding of family farming. To be sure, farmers have always borrowed from banks and other lenders to buy land, and many have rented land from other private owners. But with farmland investment funds, the link between landownership and farming is becoming more tenuous. Indeed, investment analysts, agricultural commentators, and some farmers increasingly see no necessary connection between the two. As tenants for distant landlords, independent farm operators still assume all of the production risks but without the security of having their names on the deed.

One Earth Farms, where investors are entering directly into agricultural production, raises additional issues. First, it represents the establishment of a publicly traded corporation in a sector that has hitherto been dominated by family farms. While farmland ownership and leasing laws currently prevent the further development of this trend, this could change if laws are liberalized in the future. Second, while First Nations retain ownership of the land enrolled in One Earth Farms, their involvement in the venture must be contextualized within colonial policies that dispossessed First Nations of their lands and which, as historian Sarah Carter puts it, “deliberately discouraged” Aboriginal agriculture. More recently, difficulty accessing agricultural credits and subsidies mean that First Nations have continued to struggle to engage in the agricultural economy in a way that meets their social and economic needs.

Finally, if farmland investment funds and One Earth Farms redefine both the scale and social relationships of farming on the Prairies, they may also advance a model of agriculture with negative ecological and social effects. Each of these initiatives seems committed to a type of very large-scale, capital-intensive, and fossil fuel- and technology-dependent agriculture. Prairie farms have been heading in this direction for decades, but the new investments in Prairie farmland and farming could be speeding up the trend.

Ecologically, the convergence on a model of giant, industrial-style farming may leave the sector more vulnerable to climate change and peak oil. Many civil society groups, academics, and international agencies such as the Food and Agriculture Organization of the UN suggest that diversified, small-scale agriculture is better suited to dealing with these shocks.

On the social side, the new farmland investments promote a form of rural development that replaces labour with machinery, erodes farm numbers, and extracts capital that could otherwise circulate in local economies. Such effects will be felt beyond the farm, illustrating the potential impacts of farmland investment funds and One Earth Farms on the weakening fabric of Saskatchewan’s rural communities.