From daring superheroes to good wives, from sexually liberated, fashionably chic icons of femininity to professional women employed as CEOs, the mass media provide us with images of women that are increasingly variegated and complex, seeming to transcend the binary of vamp versus virgin.

In this climate of seemingly diverse media representations, women who are victims of violence are often accused of playing the victim card. The idea that these women are able to choose victimhood over resilience and survival is a lie embedded in the neo-liberal ethic of consumer society and obscures the structural conditions that mediate and constrain the latitude of choice. The illusion of choice and the generalization that we have attained equity in representation disguise women’s diversity. In fact, not all groups of women have transcended the representational binary of virgin and vamp, nor do all classes and races of women enjoy the same privilege of seeing themselves reflected back in the metaphorical mirror of the mass media in ways that speak to their truth. Representations of women continue to be shaped by the hegemonic powers behind the scenes.

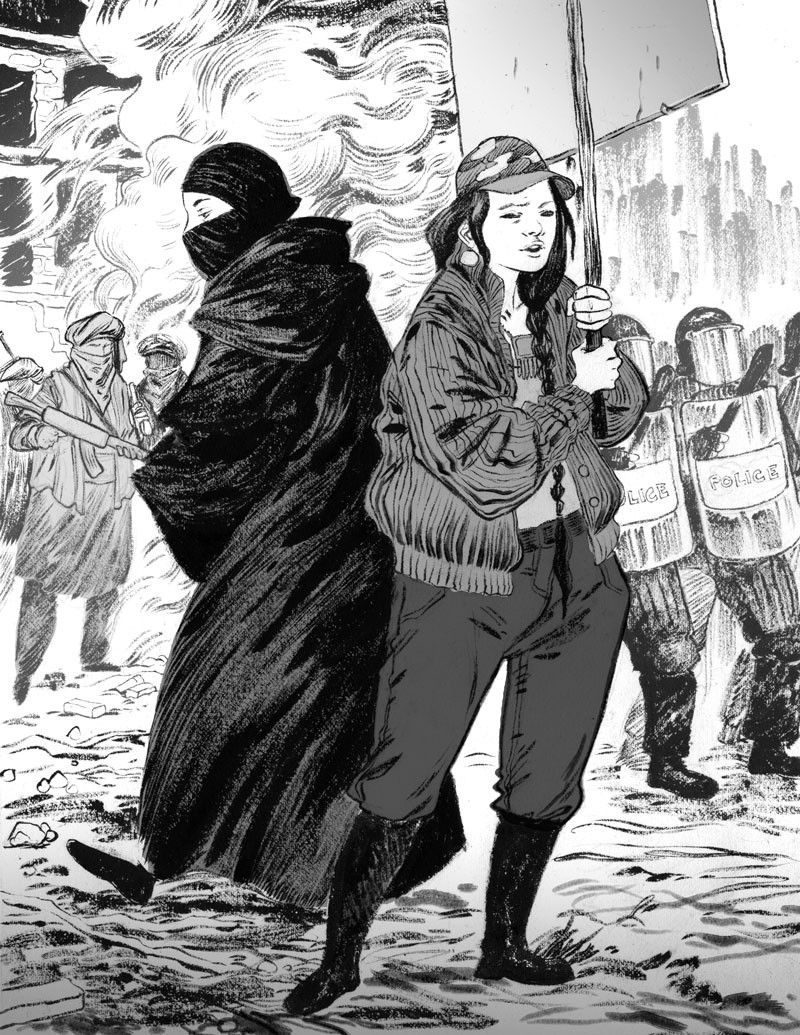

In news coverage of violence, women are almost always portrayed as victims. Whether they are worthy, innocent victims in need of rescue (“virgins”), as in the case of Afghan women post-9/11, or unworthy, culpable victims to be ignored or incarcerated (“vamps”), as with Indigenous women in Canada, depends on their strategic value to the forces in power.

Whose news?

Nowhere is the play of binaries more apparent than in news coverage. Enjoying the mantle of legitimacy as a truth-teller, the news serves to reinforce the dominant ideology. The structure of the news media, and the connotative associations that combinations of particular words and images can invoke, allows it to communicate messages that not only resonate with so-called common sense but also affirm it.

The connotations of the word terror, for example, when accompanied by images of the events of 9/11, induce an audience to complete an unfinished story. They are forced to draw from the collective stock of knowledge that is made possible by previous news stories, past experiences and historical knowledge, thereby reproducing collective understandings that are often laden with stereotypes and inaccuracies.

Speaking of the media as a repository of this common-sense knowledge, cultural theorist Stuart Hall argues, “You cannot learn, through common sense, how things are: you can only discover where they fit into the existing scheme of things” [emphasis in the original].

News programming relies on scripts, templates and frames that are anchored in this stock of common-sense knowledge. How one tells a story is then contingent on how that story has been told before and is also influenced by the constraints of a given medium. In the news media, such constraints have to do with the overreliance on elite sources, like governments and community leaders, as well as the criteria of newsworthiness (threats to the nation, extraordinary events, and anything that ruptures the routine of everyday life, for example). These criteria are not gender neutral. Numerous studies have pointed to the gendered nature of news coverage focusing not only on the ways that women are under-represented and ill-represented, but also on the reliance on masculine scripts and a focus on issues that have little to do with the daily lived realities of women.

Women as victims in the news

As scholar Ian Connell argues about television news, the bifurcation of news is most readily evident in the dichotomy between those who are “done to” as compared to those who are “doing.” Whereas female heroes populate the television programming schedule, in the news, and especially crime news, women remain largely confined to the realm of victimhood as those who are “done to.”

Where they are “doing,” it is often because they have transgressed the moral order or transcended limits upon them. For instance, in crime coverage of women as perpetrators of crime, they are positioned as transgressors of the moral order, as violating gendered norms by engaging in behaviour that is unfeminine and non-maternal. The same cannot generally be said of the reporting on men who commit crimes, in which there is very little emphasis on the role of their gender (unless male sexuality is seen to be the root of the crime as in sexual murders where the perpetrator is often assumed to have an uncontrollable sexual urge – a common rape myth according to author Helen Benedict).

Since crime news is about communicating morality tales, women’s bodies become the vehicles through which dominant society communicates its messages of morality/immorality and hierarchies of worthiness. While some women are constructed as authentic victims deserving our sympathy and attention – or, in Judith Butler’s words, worthy of saving – others are constructed as unworthy of such attention.

In her comparative analysis of the coverage of the war in Kosovo, gendercide scholar and past journalist Augusta Del Zotto found that war coverage tends to portray women as passive refugees, waiting wives, war casualties or rape survivors. Only a minority of stories included representations of, in her words, “touchy-feely” peace activists or of women as non-state, non-stereotypical actors. She concludes that, “Until news agencies radically shift the standards for what constitutes ‘news of war’ and ‘news’ overall, women will continue to be framed as victims or spectators rather than as transformative agents in world events.”

Women and/in war

War coverage and the representations of women in conflict zones offer a related area of inquiry. What constitutes a war, as opposed to conflict, invasion or genocide, invariably depends on whose interests are served by that definition. In the contemporary climate spawned by the war on terror, women’s bodies are once again being used to mobilize dominant ideologies and justify imperial incursions into other lands. Just as in the colonial period where colonized women were constructed as helpless victims in need of rescue or as savage women who needed to be contained and/or annihilated, so too in this contemporary period are colonized women’s bodies the site of contesting forces.

Women’s role as “reproducers of the nation,” as scholars Floya Anthias and Nira Yuval-Davis articulate, and as vehicles of nationalist fantasies make them of particular strategic interest to colonizing forces. In the context of the war on terror, journalist and scholar Eric Louw has pointed out that the Pentagon deliberately sought out humanitarian causes that it could mobilize as part of its public relations campaign to shore up support for the invasion of Afghanistan. The Taliban’s oppression of women had been a long-standing concern among women’s organizations and NGOs, yet the issue did not achieve U.S. government support or a global hearing until it was regarded as ideologically useful.

Women who are part of the imperial mission stand to gain a sense of their own superiority vis-à-vis their suppressed counterparts. It is not surprising to see white feminists rally around the oppression of women in Afghanistan or elsewhere. The oppression of Afghan women is a strategic foil by which western women are made to feel liberated. The Feminist Majority Foundation’s campaign in the U.S., which scholar Ann Russo has discussed in considerable detail, is a case in point. The foundation issued postcards depicting the blue mesh of the burqa worn by women in Afghanistan as publicity for their campaign to raise awareness about the plight of Afghan women. Similarly, post-9/11 speeches by prominent leaders’ wives – Laura Bush in the U.S. and Cherie Blair in the U.K. – consistently emphasized the subjugation of Afghan women in comparison with western women, underscoring the oppression of the Other while celebrating the egalitarianism of the West.

Similar messages abound in Canadian news with women reporters and columnists often focusing on the plight of Afghan women while ignoring women’s oppression in the West and instead celebrating their liberation. A poignant example was in the early reporting on the war on Afghanistan when two different female reporters for The Globe and Mail donned a burqa to experience what it would be like to walk around the city of Toronto as a Muslim woman. They wrote that it was confining and made them feel subordinate to men. The subordinate status of Afghan women stood in sharp contrast to the choice of these western reporters to wear the burqa and discard it when their experiential journey was over.

Legitimate and hidden wars

The notion of a war on terror (and a global war at that) and its overwhelming prominence in post-9/11 discourse eclipses other ongoing wars – the war against poverty, for instance, and also the war against women, particularly Indigenous women. The continuous and salient coverage accorded to the war on terror in the global theatre removes consideration of the daily war on the ground.

Unlike women oppressed under the yoke of the Taliban’s Islam, Aboriginal women’s reduced and subordinate status under Christianity and its missionizing legacy is scarcely considered an issue worthy of examination. All history of Aboriginal subjugation by white settler society is absent from most news accounts. Where such history seeps in, it is often as a backdrop by which to display how an exceptional woman transcended her destiny because of the benevolence of white society. The popular rendering of the Pocahontas legend, the Indian princess who was Christianized and who betrayed her people for a white man, works toward that end.

The war against women has scarcely been legitimized as a war in the public sphere at large, but feminists and antiviolence advocates have long called attention to the connections between violence against women in the interpersonal sphere and the institutional, national and international spheres. While the actors in the war on terror – heroes and villains, victims and perpetrators – are well defined, those in the theatre of domestic soil in the war against women are shrouded, undefined and, for the most part, invisible. This is most evident in the war against Aboriginal women.

In contrast to the hypervisibility of the abject, helpless Afghan woman in need of rescue is the sheer invisibility of the Aboriginal woman. The war that Indigenous women experience on a daily basis is scarcely given the light of public attention. Rather, it is submerged in a discourse of illegalities and immoralities, cast outside the boundaries of normative society. The frame of culpability governs Aboriginal women’s bodies in the news media.

Afghan women’s stories of resilience and contestation of Taliban power are repeatedly celebrated in the news media, whereas Aboriginal women standing up to power are most often represented as deliberately putting themselves in harm’s way. They are generally portrayed as prostitutes without regard for the moral structures of society, inept mothers constantly being brought before the courts for child abuse or having their children apprehended by the state, irresponsible women who cannot utilize birth control and hence produce numerous offspring, addicts who cannot control or manage their addictions or as failed women who cannot live up to the standards of middle-class normality that society asks of those it considers to be citizens. These dominant frames entrap Aboriginal women in the mantle of unworthiness, further highlighted by their constant representation as recipients of Canadian state benevolence and as childlike and demanding.

Additionally, the portrayal of certain groups of women, like these Aboriginal women, as culpable and impossible or not worth the effort to save absolves the state of any responsibility. In fact, the Harper government’s March 2011 legal brief in defence of current sex work laws argues this very point – that the government “is not obligated to minimize hindrances and maximize safety for those that do so contrary to the law.”

Violence as hypervisible or invisible

Contemporary representations of violence against Aboriginal women are only done a disservice by the heightened focus on the presence of a serial killer. Extensive coverage in the Canadian news of the 2007 Robert Pickton trial in B.C. is one recent example. Exaggerated emphasis on the presence of a serial killer serves a twofold ideological purpose. First, the focus serves to condense all of the violence into a singular character understood to be an aberrant deviant. His presence thus works to expunge the history of violence meted onto Aboriginal bodies, obscuring gender violence as a systemic phenomenon. Second, he is portrayed as a threat to all women, thus occluding the specificity of Aboriginality. In reality, serial killers tend to prey on the most vulnerable members of society, targeting bodies that are considered disposable and unworthy of societal concern.

The hypervisibility in Hollywood and crime news of the serial killer (including his motives for killing women) stands in stark contrast to the invisibility of the actions and motives of conquering troops in the lands they invade. While Afghan women’s victimization under Islam and particularly under the Taliban is held up as a prop for imperialist venture, the underside of that – the violence enacted on these women’s bodies by conquering troops through rapes and femicides – is rarely mentioned in the news media. When it is mentioned, as in the case of American soldiers’ rape and murder of Iraqi women (for example, Abeer Qassim Hamza al-Janabi and her family in Iraq), the behaviour is once again attributed to the lone soldier or the corrupt group of soldiers who have strayed from the noble mission of rescue.

In either case – the corrupt soldier(s) or the serial killer – both know which bodies are expendable, which bodies don’t matter. The hypervisibility of these lone, pathological men contrasts with the invisibility of the victims.

Women as tools of hegemony

The news media deploy particular narratives to define which bodies are considered worthy of attention and concern based on their ideological value in affirming hegemonic values. The focus on Afghan bodies out there diverts attention from Aboriginal women’s bodies over here and also withdraws any consideration of the Afghan woman refugee living in the West as feminist scholar Shahnaz Khan has compellingly argued.

The capacity to transcend the binary of vamp and virgin or Madonna and whore is restricted to a particular range of women. Those caught in between the two ends of the binary are mediated by the notion of victimhood and constructed either as a legitimate, authentic victim deserving compassion and/or rescue, or as an unworthy victim whose life simply does not matter.

If women are indeed “reproducers of the nation,” not only bearing children who will populate the nation but also socializing and transmitting knowledge to those children and encoding them with a sense of national identity, then we need to take a look at why women are being depicted as victims, which women are then hidden and which are highlighted, and the ensuing implications for how we define nationhood.

With Canada now engaged in another war in Libya, it is important that we keep a critical eye on the media’s portrayal of violence against women abroad and also urge them to pay more attention to the ongoing violence against women here at home.