“Can you imagine a world without prisons?”

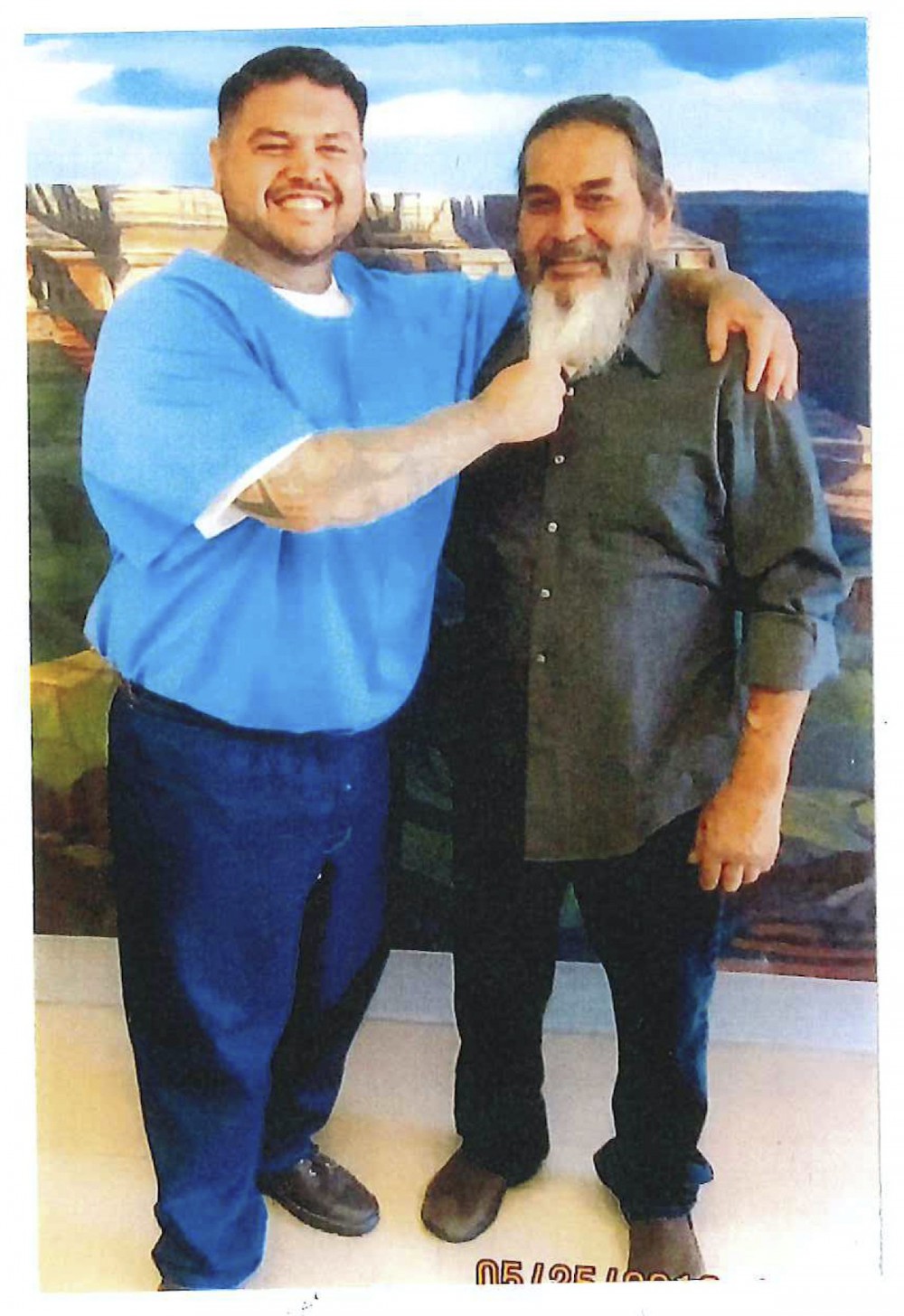

Yes, I can, but it was difficult at first because these cages have been a part of my life since age five, when police kicked in our door and took my dad to jail and left me with my mom, who was suffering from a heroin addiction. In a world without prisons, my dad would have gotten help instead of a cage, and my mom would have gotten treatment instead of being left alone to raise me.

In a world without prisons, young boys and girls won’t feel like they have to kill themselves because the prosecutor won’t offer them a plea that’s less than 25 to life.

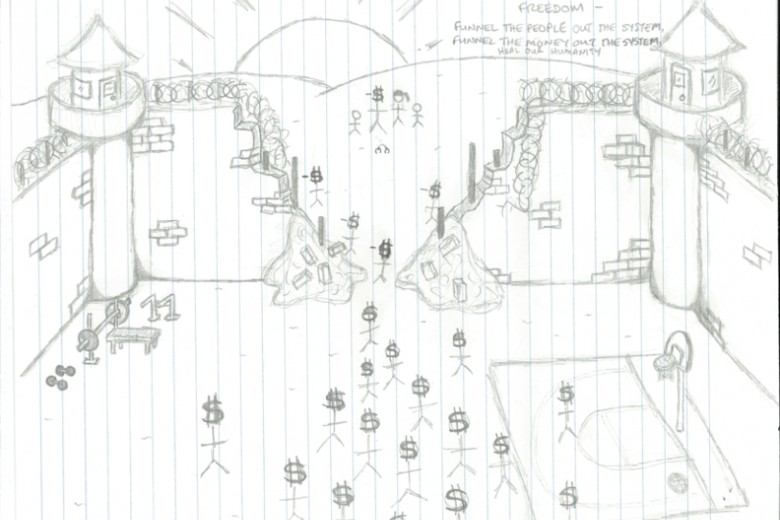

In a world without prisons, people will only be put in a safe room until they are coherent, sober, and stable. Then treatment would begin immediately. A professional will assess the breakdown in reasoning or logic that led to the crime and create a plan, including the victim’s and offender’s family, to set them on a path to healing. All parties should be asked what they want, what they need. As a society, we should be willing to put the full amount of money that we previously spent on incarceration toward this new system. This new system would perpetuate a new, healthier society that would prosper over the long term. Eventually crime would wither away in a more loving world. Parents would be there for their children. Siblings would be there to be role models and support each other. Eventually, every citizen would discourage crime, because emotional and cognitive empathy would be taught in grade schools. Healed people heal people.

In a world without prisons, my dad would have gotten help instead of a cage, and my mom would have gotten treatment instead of being left alone to raise me.

We can’t base laws on emotion. Members of my family have been murdered and nothing will bring them back. Sending someone to prison won’t heal you, and if every killer was a homicidal maniac then wouldn’t California’s 26,000 murderers have killed off the other half of the prison population?

I’d like you to know, world, that every prisoner has a mental health issue, or they would not have committed harm to themselves or others via crime. I’d like you to know, world, that 365 days is a long time. That’s an average of 30 important family events – birthdays, graduations, doctor’s visits, plus all the holidays – all without you. This absence leaves holes in the lives and hearts of our family, while we sit in prison far away. A decade is a long time and so is half a decade. It’s enough time to earn a college degree and graduate from five different rehabilitation programs, go to therapy, and become a new person. Studies show a bachelor’s degree reduces the rate of recidivism to less than 5 per cent; a master’s degree reduces it to 0 per cent. So, as a society, it would make more sense to sentence someone to education instead of prison.

Sentencing me to die in prison at a young age felt like you gave up on me when I needed you the most! We talk about recidivism as if people are beyond help, but what is a prison sentence without rehabilitation? Of course people will come back if we don’t help them to be better. We say things like, “That’s their fault, they made the choice, what are we gonna do – hold their hand?” Well, yes, what’s wrong with that? When did we, as a nation, become so angry toward our own people? Sometimes holding someone’s hand can save a life.

I wish someone would have grabbed my hand and said, “Come on, let’s go this way, Jessie.”

So, as a society, it would make more sense to sentence someone to education instead of prison.

Another thing I’d like the world to know is that punishment and justice don’t require a cage. At some point, we have to look at what we’re doing and ask, “Is this what’s best for all our people? Is this helping or hurting our community and society? What happened to the families left behind?” Single-parent households are created, burdens are increased, kids are left without mothers and fathers and stuck in poverty. Then we point to the one who happens to make it – out of the thousands who don’t – and we say, “Look, that person made it, so they all could! It’s their fault,” and we sit back while generational poverty, trauma, and incarceration are the norm for millions in our country. At what point do we say “enough!” and start tearing down prisons and building treatment centres, education centres, houses of healing and not pain?

My cousin was killed when I was little. He was like my big brother and it destroyed my world view. The guy who killed him, I heard, was a cop’s son and no charges were ever filed. My cousin’s name was Anthony Northrup. What did we need as a family for us to heal? We didn’t need the murderer in prison; we needed him to say he was sorry and to see the hole he created in our life, to develop remorse and change, so he would not take another life.

When you offend someone, the first thing you owe them is an apology, and then you have a duty to understand why you did what you did, so that you can make sure it doesn’t happen again. Then you should have a conversation, asking the victim what can be done to help them heal, aside from vengeance. We should avoid vengeance for a couple of reasons: one, vengeance is costly, at $70,000 a year to cage one person; and two, vengeance doesn’t help anyone heal – in fact, it perpetuates the cycle. Unhealed wounds fester and get worse, and they manifest themselves in all sorts of unhealthy ways like addiction, anger, and depression. Little children grow up angry at the world. Their dads are in jail, and without the tools to cope, they repeat the cycle. Imagine what that $70,000 a year for each prisoner could do elsewhere. Imagine if we redirected that toward the 270,000 homeless kids in California alone? Is incarceration really the best way to spend our resources? We promulgate the myth that incarceration is necessary to keep this dangerous person off the street, but I haven’t assaulted anyone during my entire 18 years in prison. It’s not that I can’t – I just choose not to because it is not who I am. Yet, around $1.2 million has been spent to cage me thus far. And there are 128,000 other people in California prisons, not including the county jails, federal institutions, and juvenile detention centres. True crime prevention would be to invest in our communities and the mental health of their inhabitants. People deserve better from their governments, and tax dollars should be spent to create better futures for us all. We can demand that future through our vote and who we elect to office. After all, the government works for us.

What did we need as a family for us to heal? We didn’t need the murderer in prison; we needed him to say he was sorry and to see the hole he created in our life, to develop remorse and change, so he would not take another life.

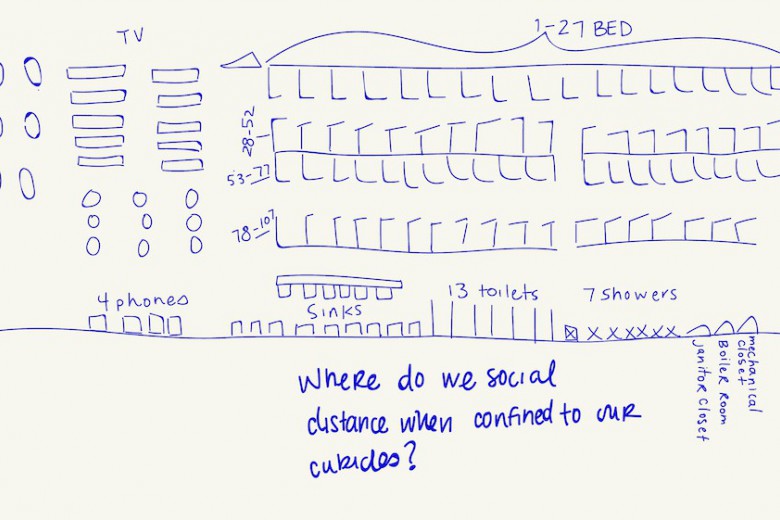

During COVID-19, the topic of prisoner health care has been front and centre, but it always seems strange to me that the state has sent us here to die, and now people are concerned about our health. The biggest threat to my health and well-being is my 174-year-to-life prison sentence. COVID-19 is new, but incarceration has long been a pandemic. It’s part of a culture of devaluing human life, which includes referring to us as “parolee,” “defendant,” “offender,” “criminal,” or my favourite, “suspect.” An officer told me last week, “You choose the crime, you choose the punishment!” I told him that sounds like a guy I know who used to beat his wife, who would always say, “If she didn’t want to get beat, she wouldn’t have stayed out late.” It’s terminology used to justify abuse. Most people who commit crimes do so while on drugs, in mental health crisis, desperate, and poverty stricken – they are not making rational, educated, informed decisions. Yet we as a society make educated, rational, informed decisions to take human life by sending people to die in jail. Who’s committing the great offence toward humanity?

I’d also like society to change how they refer to or classify prisoners as “violent offenders,” “non-violent offenders,” or “drug offenders.” The crime a person committed 20 years ago is not indicative of who they are today. The crime committed years ago is what they did and not who they are, back then or today. So when we refer to people for release, how about we refer to who they are today – for instance, to release me, you would say, “let’s release the kitchen cook, who’s Christian, has straight As in college, is always positive, and values his family and kindness.” In my experience, the most non-violent prisoners are the ones convicted of violent offences. So please reconsider your terminology. I encourage you all to reconsider not just how you speak but how you see and feel.

Yet we as a society make educated, rational, informed decisions to take human life by sending people to die in jail. Who’s committing the great offence toward humanity?

Sadly, my uncle was killed on September 17, 2020, allegedly by my nephew. I was heartbroken but I don’t wish prison on him. I wish remorse on him – I wish that he change and love, LOVE himself so he can LOVE OTHERS. If I can do this for my nephew then why can’t we do this for your nephew, your father or brother? We can. We don’t have to wish prison on anyone; it doesn’t help or make the pain go away. Prisons ensure we all stay broken. If we can see ourselves in each other then we can get beyond the blame and vengeance. If I can see your son as my son, and you can see my son as your son, and the murderer and victim as one – each of them human – then we can build a better world, a more loving world, where treatment is valued over vengeance, people get help instead of death or cages, our resources are used to care for the least of us, and no children are homeless tonight in our city, our town, our world.