While buying a cup of coffee at a local café one morning, I was transported to an exotic far-off land. Immersed in the aroma of coffee brewing and surrounded by pictures of farmers picking coffee and their children smiling, I could imagine who had grown the coffee in my mug. Fair trade marketing materials littered the countertop, thanking me for buying fair trade certified coffee and telling me that I was making a difference and that fair trade works. My single cup of coffee was said to help poor farmers. One of the posters declared “every purchase matters,” and another said I was helping end poverty “one cup at a time.” The promotional materials explained that my purchase brought me into a direct and intimate relationship with farmers as if the handle of my coffee mug were a farmer’s hand I was shaking to congratulate him or her on a job well done.

Fair trade marketing and advocacy rely on the idea that fair trade increases connectedness between Global South producers and Global North consumers. But while fair trade does reduce the number of intermediaries in the supply chain as compared to the free trade system, it also serves to reinforce racist and colonial distinctions between the poor Global South farmer and the benevolent Global North consumer. While it may channel slightly more income into agricultural communities, it ultimately fails to address the colonial capitalist structures that produce the impoverishment of farmers on an ongoing basis.

Contradictory history

Although now thought of as a single movement, the fair trade movement originated as a hodgepodge of diverse interests, including anti-colonial struggles, colonial civilizing missions, a variety of grassroots alternative economic activity and more. Given this history, it is perhaps not surprising that fair traders – from producers to traders to certifiers to advocates – do not share a common set of values. The current contradictions between the movement’s stated goals and its subversion of those goals in practice are grounded in the contrasting anti-colonial and colonial initiatives that comprise the movement’s roots.

Colonial politics

The distribution of power in the fair trade industry is remarkably similar to colonial divisions of the globe, with fair trade certified commodities produced in various former colonies and sold in niche and mainstream markets in Europe, North America, Japan, Australia and New Zealand, where decision-making power in the certification system is concentrated. The movement by and large does not include production from Indigenous communities located in white settler colonies like Canada, the U.S., Australia, and New Zealand, nor non-Indigenous producers in places like Canada and the U.S. who often exploit migrant workers with little heed to basic labour rights.

Decision-making power within the international fair trade certification system rests largely with national labelling initiatives – organizations that certify and help promote products in their region. The structure of Fairtrade International, the most prominent international fair trade certification agency, is indicative of the severe disparity in decision-making power between actors from the Global North and the Global South: 19 of the 24 members that compose Fairtrade International are labelling initiatives based in the Global North. The remaining five members include three producer networks (one each for producers in Latin American and the Caribbean, Africa and Asia), and two non-voting associate members, Comercio Justo México and Fairtrade Label South Africa. The fair trade certification bureaucracy spans the globe, but its centre of governance is in Europe.

Despite being organized into co-ops (which Global North traders are generally not inclined or required to do), and therefore well-positioned to make collective decisions that affect their families and communities, fair trade producers have very little voice when it comes to determining certification policies and the structure and direction of the fair trade movement.

Fair trade fantasies

This geopolitical inequality is further entrenched in the minds of Global North consumers through fair trade marketing, which romanticizes the lives of producers and the effect fair trade has in their communities.

Businesses that sell fair trade products do so by commodifying justice and consciousness and marketing them to middle-class consumers. Fair trade coffee roasters across Canada and the U.S. use slogans such as “coffee with a conscience,” “brewing justice,” “common ground” and “higher ground” in trying to sell their products as ones that “make a difference.”

Fair trade products are personified, often touted in advertisements, packaging and campaigns as having a conscience and the capacity to speak to consumers. Fair trade advertising appeals to and produces a specific type of “conscious” consumer who is called upon to vote with their money and to reach through their coffee cup to realize their imagined heightened connection to deserving producers.

What’s in a label?

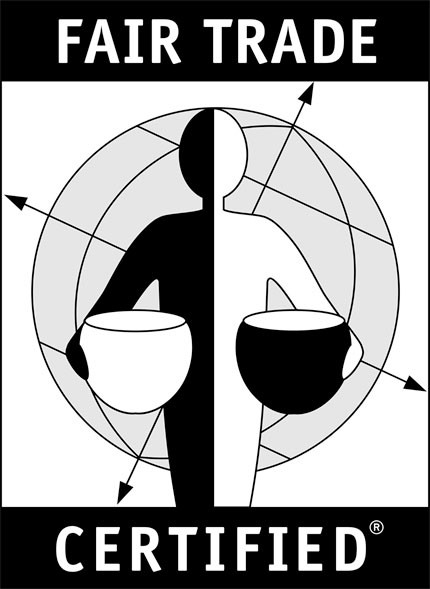

The certification mark used by Fair Trade USA portrays a half black, half white person whose black hand is holding a white cup at the same height that their white hand is holding a black cup. This label looks like Lady Justice with her blindfold and balanced scales, and promotes the idea that fair trade is about justice and equality. Since fair trade producers aren’t generally seen as white, this label racializes consumers as white and producers as black, portraying the relationship between two categories of people – consumers and producers, developed and developing, metropole and colony. The image suggests that North Atlantic imperialism is in the past, that Europe and its others are now fused as one. Contrary to the fantasy this image promotes, fair trade does not operate in a power vacuum and is not an exchange between equal participants.

The certification mark used by Fairtrade International is a take on the yin-yang symbol and suggests a dialogical relationship between two seemingly polar opposites, which, when viewed together, reveal their interconnectedness and interdependence. This image implies that there is a little bit of them in us and a little bit of us in them. Rather than being mutually exclusive, consumers and producers are inherently entangled, perpetually co-creating and reinforcing one another. The image can also be interpreted as a human figure with an outstretched arm, which could be a producer reaching toward the hand of a consumer, or vice versa, invoking the fantasy that fair trade involves a heightened connectedness between producer and consumer.

‘Higher ground’ – the danger of moral righteousness

In the Global North, fair trade advocates work to convert the support for free trade, unconscious or otherwise, into conscious support for fair trade. One effect of this conversion is that consumers of fair trade products feel a sense of distinction vis-à-vis “unconscious” consumers. The “conscious” consumer feels secure, even righteous at times, in their perceived morally superior position to the “unconscious” consumer.

This points to fair trade’s cyclical process of commodity fetishism: while fair trade campaigns may defetishize or devalue certain products by making visible some of the unjust conditions of production, many of these same campaigns refetishize products and their producers by imbuing them with a reified exotic character.

Many fair trade promotional materials rely on a perception of producers as primitive people from exotic, far-off lands. This understanding of producers is constructed and supported by the development industry. In the developed/developing dichotomy, those who are said to be developing are thought of as existing in a time previous to those who are considered developed, a simpler time that the developed world grew out of long ago. This model assumes everyone in the world is working toward the same end and that everyone understands development as the same thing.

This dichotomy points to a paradox. Fair trade claims to bring people who are understood to be from two orders of humanity closer together. Global North fair traders extend a hand to producers while simultaneously banishing them to a previous social order. Consumers and producers cannot be brought closer together when they are thought of as existing in different times and worlds. Reducing the number of intermediaries in the global commodity chain cannot close this distance, and simply coming up with new terms to describe the relationship won’t do it either.

Solidarity with producers starts with seeing them as human and worthy of respect. Colonial relations are not just material, but also relate to ways of thinking about various people, places, commodities and the world at large. Decolonization is not just a material process, but also a mental one.

“Fair trade is better than free trade”

The above slogan, which has been used in many fair trade campaigns, sums up the imagined dichotomy of the two trading systems. Fair trade is both bound to the history that produced it, including colonialism, capitalism and free trade, and mildly critical of the present political and economic circumstances produced by that history. The movement is not set up to triumph over free trade and will never do so. Fair trade is a means, not an end. It is meant to be a path toward a more just future, but, while it may make an economic difference in producers’ lives in the short term, it also participates in the continual reproduction of global power imbalances that keep producers everywhere (though some more than others) at a disadvantage.

So what can we do about it?

Simply being a conscious consumer is not enough. Wise choices about consumption are most effective when used in concert with other actions and initiatives that challenge the underlying structures that produce local and global inequality.

1. Expand your conception of fair trade. In addition to addressing power imbalances between the Global North and the Global South, consider forms of trade that support local farmers and Indigenous communities. Support Indigenous land claims, sovereignty struggles and movements against the exploitation of natural resources by transnational corporations and neo-liberal governments the world over.

2. Do your research. Support and work with businesses that are locally owned and operated and work with communities near and far on a basis of mutual accountability, respect and solidarity, especially co-ops in Canada and the U.S. that operate on a strict co-op-to-co-op trading policy.

3. Check out the following initiatives:

La Via Campesina: a global, peasant-based movement that defends small-scale sustainable agriculture in the name of social justice and dignity. An autonomous, multicultural movement, it comprises 150 local and national organizations in 70 countries and represents about 200 million farmers.

Domestic Fair Trade Association: a multi-sector alliance of farmers, farm workers, retailers, manufacturers, processors and non-governmental organizations in Canada and the U.S. that are dedicated to bringing the principles of international fair trade to trade within North America.

The fairDeal: a new certification label that encompasses multiple standards under a single seal, offering consumers in Canada and the U.S. the opportunity to purchase local and regional products that adhere to organic, fair trade and labour standards. The initiative emerged as a response to the watering down of organic standards and the absence of fair trade standards for North American products. The Domestic Fair Trade Association (above) and Farmer Direct Co-operative, based in Saskatchewan and co-operatively owned by 70 farmers in western Canada, have been instrumental in its development. fairDeal flaxseed, lentils and split peas are now available throughout western Canada and the pacific northwest in the U.S.

Cooperative Coffees: a coffee importing co-operative that comprises 24 community-based coffee roasters in Canada and the U.S. Canadian members include Alternative Grounds in Toronto, Bean North in Whitehorse, Café Cambio in Chicoutimi, Café Rico in Montreal, Coutts Coffee in Perth, Equator Coffee in Almonte and La Tierra Coop in Ottawa.

Local Food Plus: a non-profit organization that is developing a comprehensive certification system for standards of production, labour, native habitat preservation, animal welfare and on-farm energy production. The organization focuses on community economic development and seeks to evoke the widespread, large-scale change required to keep farming a viable industry.

La Siembra Co-op: Owner of Camino, which produces certified fair trade, organic chocolate and baking ingredients, La Siembra is a Canadian worker co-op that does most of its trade with other co-ops.

Toronto’s Westend Food Co-operative: a multi-stakeholder co-op that brings together farmers, food store workers and consumers all in one co-op.

Family Farm Defenders: a non-profit advocacy group that promotes the creation of a farmer-controlled and consumer-oriented food and fibre system.