Most important, I am worthy, I am alive, and I love being who I am. – Gloria

Candace, Donna, Gloria, Kathryn, and Lisa left the Blackfoot Piikani and Kainai (Blood) reserves on a Sunday. They were making the long road trip from southern Alberta to Winnipeg to the 2013 International Indigenous Voices in Social Work Conference to present a special project to attendees. Finished just weeks earlier, the project involved two emergency shelters these women had used when experiencing domestic violence.

We, the project team, had asked them and eight other Blackfoot women to share their experiences and their expertise, to improve shelter services. Through the Blackfoot practice of shawl-making, these women had shared stories of abuse and created a spirit of hope and strength for a life beyond violence.

Now we had asked these women to share their stories and spirit again. Throughout the conference, they were the only project participants in a sea of social work practitioners and academics. Yet they proved to be a magnetic force, attracting people who were curious, friendly, and supportive, making connections everywhere, in the corridors and at mealtimes. By the time of their presentation, people were eager to hear their story.

It is an honour to be here, and it is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity for me to present at a conference such as this. – Lisa

These women’s stories make up part of a much larger crisis that has been silenced in Canada: the widespread violence experienced by Indigenous women. Sources including Amnesty International report Indigenous women in Canada are between five and seven times more likely than non-Indigenous women to experience domestic violence – and it is often more serious. Momentum is building for a national inquiry into the estimated 824 missing and murdered Indigenous women in Canada and for a national action plan on violence against women that would coordinate existing policies and bolster preventative action.

These would represent important steps toward raising consciousness, introducing accountability, and, most critically, saving lives. Yet even in a best-case scenario there will remain thousands of traumatized Indigenous women survivors who have lost their children or their homes and experienced the deterioration of their physical and mental health. How can we help the survivors and those still at risk move to the positive future they deserve?

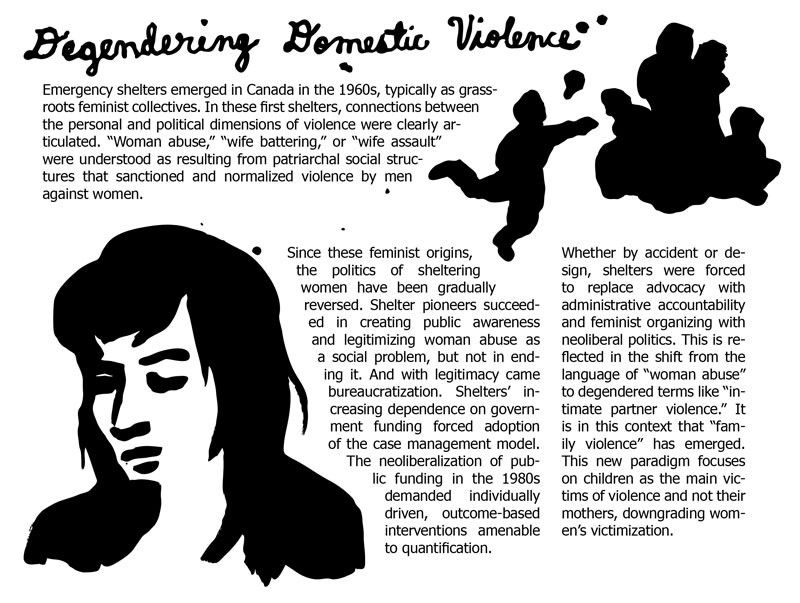

Domestic violence in the colonial present

When I picked out my shawl, I was thinking about my past and abuse I went through. My life was dark and gloomy. – Donna

Our project at the women’s shelters privileged both the women’s articulation of their needs when experiencing domestic violence and their recommendations for how services on and off reserve can best meet them. Our research methods were Blackfoot shawl-making and participatory appraisal exercises, the latter borrowing heavily from Paulo Freire’s critical pedagogy for research with oppressed people. This methodology committed us to meeting the women on their own terms, to generate experiential knowledge that could spur community-based action for improving domestic violence services.

Shawl-making also allowed the women to share their stories and recommendations for domestic violence services in a culturally appropriate way. The Blackfoot have made shawls for centuries to create the sacred attire for ceremony: sweat lodges, pipe ceremonies, night lodges, powwows, and Sun Dances. Designs emerge from meaningful colours and images, connecting the craftsperson or wearer to their community and a shared past.

When I went to the shelter in Pincher Creek, I was going through by far the hardest time of my life. Within a week I had my baby back, and a month later I had my very first home. – Kathryn

The women in our project were very clear that, for them, most domestic violence services are sites of harm and trauma: “dangerous spaces.” Among these they named children’s services, law enforcement, and health services – all essential, front-line agencies that deal with domestic violence victims. These women shared difficult stories about the degrading and dehumanizing treatment they experienced from service providers.

Twenty-three-year-old Kathryn spoke about child welfare seizing her daughter, just as she was starting a new job and full of hope for the future, and the racism she believes provoked that action. At clinics and hospitals, in the midst of crisis, the women endured staff’s assumptions that “they just want pills.” Across Canada, police frequently detain or arrest abused Indigenous women rather than provide immediate, appropriate support. As a result, abused Indigenous women do not seek help when needed or, if they do, their victimization is often intensified unnecessarily.

For these women, the exception to dangerous domestic violence services has been emergency shelters. Unemployed, homeless, dealing with a history of abuse and having her baby taken away, Kathryn went to “the safest place [she] could think of, the women’s shelter.” As Lisa told the audience, “The shelter is here for us, and they never turn us away.” Donna said: “I felt safe at the shelter, and I was able to leave my troubles outside. It was a time when I could actually relax.” Being able to leave problems outside and retreat into a safe space is taken for granted by many Canadians, but it is a powerful experience for women experiencing domestic abuse.

So what distinguishes the two shelters these women used from other domestic violence services? The answer is that both are committed to long-term decolonization programs. At the Winnipeg conference, attendees emphasized that colonization causes violence in Indigenous communities across the globe. In Canada, assimilation policies and resulting intergenerational trauma forces Indigenous people to, as scholar Cynthia Wesley-Esquimaux argues, “displace their cultural and spiritual activities,” causing “social alienation and profound psychological problems, such as alcoholism, drug addiction, domestic violence, and sexual abuse.”

Violence alongside poverty, poor housing and education, and substance misuse suspend Indigenous people in what Taiaiake Alfred terms “the living legacy of colonial violence.” For Indigenous women, this living colonial violence further intersects with gendered discrimination, making them disproportionately subject to violence in their homes and in public spaces.

When service providers assume Indigenous women are bad mothers or just looking for pills, they inflict colonizing violence twice over. Our project identified social services’ dominant case management model as perpetuating ongoing colonizing violence, but we also developed recommendations for how it can be changed.

Currently, services follow a westernized clinical paradigm focused on curing or “healing” individual pathology. The model separates abused women into different treatment settings like law enforcement, child protection, and physical and mental health services. Indigenous women are rendered individual actors doubly removed from their cultures and communities and the structural forces driving their abuse. Recently, with the emergence of the degendered family violence paradigm, the situation has worsened. The individualized case management of abused Indigenous women silences their voices, undermines their agency, and isolates them from their communities.

Stitching, storytelling, spirit

For my design, I gave it a lot of thought. I have a dream catcher with an eagle head in the centre, which represents my strength and courage that I have had to overcome the difficult trials in my life. My feather represents my five beautiful children and their birthstones. – Donna

Blackfoot shawl-making reverses this silencing. As she stitched her shawl, Donna shared with the group her story of abuse and alcoholism and how these damaged her relationships with her children and grandchildren.

In the group I learned that I am not alone in the challenges that I have faced in the past and now. It helped to hear the other women’s stories about what they have been through; it showed me that I am not alone, and that gave me the courage to continue on my journey. – Candace

During shawl-making, Candace spoke of her difficult past and the importance of her relationship with her young son, who gave her “strength to overcome the difficult obstacles of life.” In the four corners of her shawl were stitched her and her son’s handprints. In the centre was a bear and her cub: “They represent my son and I; like the bear family, we have a strong bond.”

Candace emphasized the benefits of listening to, and sharing with, other women experiencing violence. Throughout the conference, Indigenous people from across the world shared their experiences of violence in colonized lands. Their stories had a powerful impact on these Blackfoot women, who often commented, “They have the same problems we have.” Surrounded by people with similar life experiences, they felt a resurgence of Indigenous identity.

The shelter project sessions in southern Alberta created a collective spirit, as Blackfoot shawl-making is more than stitching. Blackfoot custom emphasizes sharing, kindness, and respect for the unique gifts each person can offer the community. Candace had more sewing experience than the rest of the group and used this to help others complete the hemming. Her gentle prodding and easygoing laughter encouraged some to use the sewing machine for the first time. Shawl-making embodies the potential of the individual within the community. Through their sewing, the women modelled Blackfoot knowledge.

I recommend that Elders be available at the shelter on a weekly basis so that we can get guidance and support when we need it. – Candace

Elders attended each project session. One, an expert seamstress and beader, guided the group on using the sewing machine, while another assisted with hemming. Elders never instructed but worked alongside the women, providing expert opinion on, or assistance with, sewing and constructing symbols when asked. The Elders were counsellors and mentors in the group. They encouraged the women to share stories of their mothers and grandmothers and also of their own lives.

By sharing their stories, Elders helped the participants understand that barriers can be overcome. It’s difficult for those in the dominant settler culture to understand how fundamental Elders are to the health and vitality of Indigenous communities. They have lived long lives and overcome many challenges and also carry knowledge from the past, reaffirming language and culture. Involving Elders in services and projects may be the quickest and most effective way to help Indigenous women move forward from violence.

Shawl-making uses Blackfoot knowledge of community and the power of collective spirit but it also creates this spirit. In contrast to the domestic violence services these women identify as dangerous, our project revealed that spaces became safer the more they embodied cultural connections. The support and guidance from Elders available in the shelters was one of the main reasons they were identified by the women as safe. This safety only increased with provision of culturally appropriate activities including spiritual programming and spaces for smudging and prayer.

Blackfoot shawl-making therefore proved a powerful tool for decolonization. The Blackfoot women in our project felt a profound sense of connection with their children, families, communities, culture, and land. These connections foster hope and strength in recovering from violence, and the women in our project clearly asked for domestic violence services to facilitate more connections not fewer. Their recommendations challenge the dominant, individualized case management model, which positions Indigenous women in fragmented, often-hostile treatment settings. The dominant approach does not prevent domestic violence; in fact, it reproduces the colonizing estrangements that fuel violence in Indigenous communities.

Indigenous people alone cannot overcome colonization’s systemic inequalities. Responding to the launch of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission into Indian residential schools, author and researcher Paulette Regan argued Canadians must “unsettle the settler within” by investigating and accepting “how colonial violence is woven into the fabric of Canadian history in an unbroken thread from past to present.”

It’s clear that domestic violence services must undergo a profound re-evaluation based on Indigenous communities’ assessments of their own needs. As a first step, we recommend all domestic violence service staff receive ongoing training in colonization’s impact on Indigenous women, their families, and communities. Our experts, 13 Blackfoot women, were adamant that all community members be invited to and included in these consciousness-raising sessions. They recommended that culturally based domestic violence service and outreach programs dedicated to traditional parenting and life skills be available to whole families, extended families, and community members.

“How did you do this?”

I recommend that this program continue so that other women [can] participate. It is a tool that helps in daily life. The best part is that after my shawl was completed, it represented … better things to come and a bright future for me. – Gloria

As the conference presentation closed, many in the audience waited to connect with the women, to say thank you, to share how moved they were, or to offer support. One attendee approached us to ask: “How did you do this?” In other words, what was the secret? Our project’s journey from first meetings with concerned community members and Elders to that climactic moment in Winnipeg was challenging and complex. But in our hearts we had one answer: relationships. Our capacity to mobilize the project resulted from trusting relationships built through significant time investment. Some of us have worked together for more than a decade striving to decolonize our part of Treaty Seven territory.

But the project’s success depended on another kind of investment: adequate, secure funding. Our project succeeded because we had funding for shawl materials, gas to transport women from rural locations, and honorariums, not to mention for staff wages, child care, and food.

In recent years, we have watched politicians across the political spectrum make communities responsible for systemic problems, using the rhetoric of community-based approaches to justify deep cuts in public funding. Listening to Gloria and the other women testify to the transformative value of the project confirmed our belief that it represented the best of community-based research. But it would never have happened without, first, adequate, secure funding; and, second, trusting relationships between communities and service providers resulting from years of shared decolonizing work. Future projects to help the thousands of abused Indigenous women forced into Canadian society’s shadow will require the same.

- This essay was the winner of our 2014 Andrea Walker Memorial Fund for women’s health writing. Special thanks to our editorial committee, Jane Kirby, Naomi Moyer, and Evie Ruddy.