We hiked for an hour to cross the cutblock, our feet imprinting the burnt earth scarred with caterpillar treads. Trampling gorse and nursing a sunburn, I followed Freddy Jolly on his path to the river. We had barely reached our destination, a frame cabin topped by a tarp roof flapping in the wind along the frozen shoreline, when Freddy Jolly handed me his binoculars.

Late April is goose season in Quebec’s Cree territory, and for two weeks the reserves in the northwest of the province empty out as schools and employers give time off to hunters returning to the bush. Shacks and teepees dot the gravel roads that connect communities. Whole families pile onto Ski-Doos and head out to remote locations to participate in the goose hunt, an age-old tradition that will supply many families with food for the months ahead.

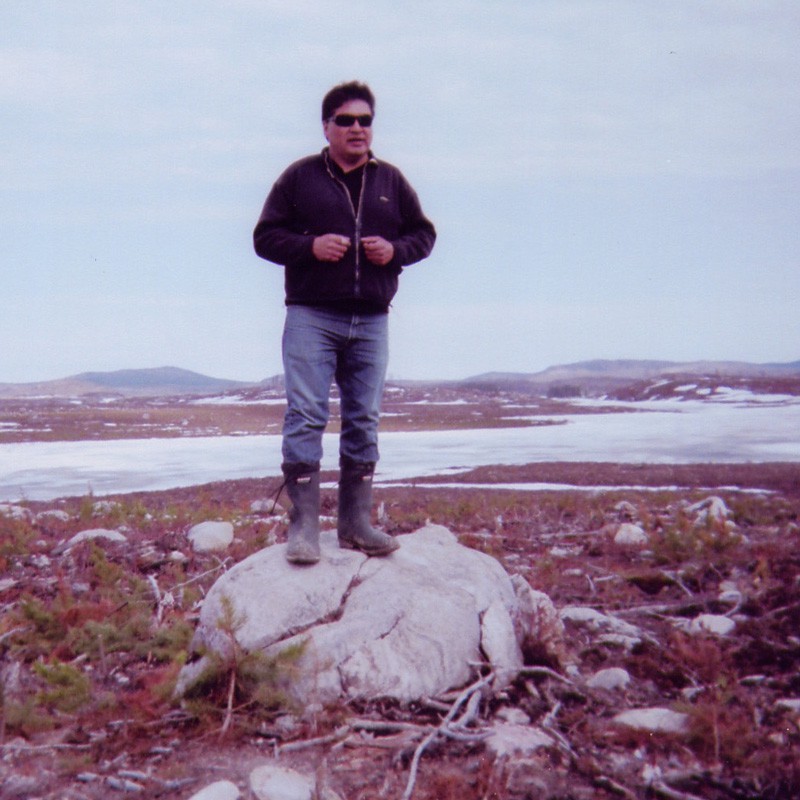

But for Freddy Jolly and others, this year’s goose season is bittersweet, indeed. In 2007, Jolly, a 52-year-old professional trapper, was paid by the province’s electric utility to oversee the felling of 13 square kilometres of spruce forest on his own trapline. The land is part of a 640-square-kilometre area that will be flooded in late 2009 once Hydro-Québec completes work, now started, to divert most of the kilometre-wide Rupert River into reservoirs along the Eastmain and La Grande River systems further north. The impact on these traditional hunting, fishing and trapping grounds—and on the culture they sustain—will be devastating. Seeking to stop the development, the province’s 16,000 Cree have tried tactics ranging from protest to legal action, but have had very little success so far in shaking the public utility’s addiction to mega projects.

Around Jolly’s home town of Nemaska, 10 out of the 15 traplines that are managed by local families will lose land to the diversion. Nemaska fishers worry that the six-foot sturgeon for which the community is noted — the town’s name means “plenty of fish” in Cree — will disappear after the river shrinks to a trickle.

The losses will extend equally to Cree heritage. The Rupert, which once served as a conduit to the fur trade, is a repository for important artifacts related to early Cree settlement, and despite the efforts of a team of salvage archaeologists, many sites in the affected area will remain undiscovered and unexcavated when the flooding commences.

Stationed at a base camp a few kilometres from Nemaska, a crew of 18,000 workers is employed around the clock to prepare the way for four dams on the Rupert and its tributaries, and to construct a spillway and a diversion channel. Trappers such as Jolly are sometimes forced to negotiate company checkpoints to reach their cabins.

For Freddy Jolly, the decision to accept the contract to cut on his trapline was fraught with contradiction. As a traditionalist, Jolly had campaigned against the diversion, speaking on Cree radio and completing a 17-day walk to draw attention to the effects the flooding would have on fish and game. But after majorities in eight of the nine Cree communities voted to approve the project, Jolly felt his options had run out.

“The trees, those are my babies,” he affirms in halting English. “I’d rather kill my babies than [let] somebody else.”

“After the work, tears would come out from my eyes, going home. Seeing the trees being cut, seeing the trees being piled and burned. It was hard.”

Jolly’s anguish reflects a broader malaise among the Quebec Cree who are beset by a sense of powerlessness in their relations with the provincially-owned energy giant.

Starting in the 1970s, Hydro-Québec has built a network of dams and diversions along the rivers that drain into the eastern shoreline of James Bay. According to its published blueprint,the utility originally expected to harness waterways ranging from the Rupert, on the 51st parallel, to the Great Whale River, on the limits of Inuit territory, in the north. Construction began near the Cree town of Fort George/Chisasibi, on the La Grande River, where the first dam was inaugurated in 1981. Through a series of diversions, the James Bay Project, as it is known, has expanded to a point where it now floods some 13,000 square kilometres of former woodland and supplies 43 per cent of Quebec’s electricity.

At the outset of the project, the Cree were neither consulted nor given prior notice of the construction, and according to oral history, they found out about the development through the newspapers. Protests arose as both Cree and Inuit realized that their traditional resource base would be damaged in ways that would threaten their way of life. As the project unfolded through subsequent decades, the Cree and Inuit forged alliances with southern activists. Through the late 1990s a two-storey-high solidarity mural that depicted a traditional Cree hunting camp and that denounced the megaproject stood on a main street in downtown Montreal. Still, among non-native Quebecers, concern for First People’s rights remained a minority perspective.

Promoted by Quebec’s nationalist icons, including Robert Bourassa and René Lévesque, the nationalization and expansion of the provincial energy grid from the early 1960s stood as a symbol of economic advancement. In a subjective but important way, reliance on hydro power also validated Quebec’s self-identity as a frontier nation, founded by river-navigating voyageurs.

Today, with the exception of one nuclear reactor and some recent experiments in wind energy, hydro remains the dominant mode of electric power generation throughout the province. The Quebec government touts hydroelectricity as “clean energy” (as compared to coal-burning plants). Under the evaluation criteria set up by the Kyoto Protocol, Quebec stands out as the Canadian province which emits the lowest level of greenhouse gases per capita as a result of its reliance on hydro.

Nevertheless, the picture is not all rosy. Environmentalists have pointed out that flooding woodland produces methane as trees and other organic matter decompose underwater. Methane is a powerful greenhouse gas, but a loophole in the agreement—methane from reservoirs is not counted under the Kyoto evaluation—allows Quebec to boast an emissions total that is inaccurately low.

Meanwhile, for Cree hunters, the ongoing hydro development has meant a loss of territory, impacting traditional game patterns in unexpected ways. Families that within living memory were deriving much of their sustenance from the land around them began to lose their autonomy.

Roger Orr, who grew up in Fort George/Chisasibi on the La Grande River and who now lives in Nemaska, was a witness to this process.

“People were still getting their water from the river,” he remembers. “And it was all hunting. Even though there were hardly any jobs, people were still very busy.”

Orr, a 43-year-old addictions counsellor, recalls the thrill of spring breakup in the old days, before the river was altered. “Even just the first crack in the ice, everybody went down to the shore to look at it,” he tells me. “And the iceflow was awesome. Big, huge chunks of ice just coming up the edge of the riverbank. And people would have to run back. And all the men would be down there with their 30-30s and their .22s shooting at the pieces of ice.

“But then that all changed.”

Orr has clear memories of the period that followed the start of construction on the La Grande in the mid-1970s. Downstream of the complex, the river stopped freezing solid. “It would freeze and it would just open up again as they were opening and closing the gates.” More changes followed, as silt choked the aquatic vegetation. “It was getting harder to get geese because they weren’t landing at our ponds any more. Some people don’t even kill any geese, where we used to kill lots.”

In parts of Cree territory, fish and fish-dependent species including seal have become inedible because of mercury that leaches from the soil into reservoir water.

For Orr, the collapse of the old subsistence base has provoked a sense of purposelessness in the community, spawning a rash of social dysfunctions including obesity, suicide and addiction. The word Orr uses for this phenomenon is ‘dependency.’

Dammed if you do . . .

In the 1970s, as the state utility expanded onto untreatied lands, the Cree fought an exhausting legal battle to block the project. As a first step they petitioned the Quebec Superior Court for a temporary injunction to suspend construction while their land claims were being considered.

In November 1973, after six months of hearings, Judge Albert Malouf issued an injunction, which was never enforced. Construction continued at the work site in the days following the injunction, and the Quebec Court of Appeals intervened to overturn the decision seven days later.

In light of this reversal, the Cree leadership realized that the dam on the La Grande River would be operational before the courts would hear the substance of their land claims case. In an attempt to mitigate their losses, they opted for an out-of-court settlement, signing a treaty known as the James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement with the provincial government in 1975.

As part of the treaty, the Cree waived their opposition to the first phase of the James Bay project in exchange for an indemnity of $130 million. The province acknowledged Cree hunting rights in a portion of the James Bay territory, and pledged to fund self-government and social services in the Cree communities, though the amount of this funding was not fully specified.

The treaty set the framework for much of the subsequent interactions between the two parties. As the utility extended its hydroelectric project according to the blueprint, the Cree protested and periodically threatened lawsuits over the details of the funding formula which had been left open.

On occasion, the absence of basic services produced a crisis — as in 1980, when a rash of deaths from gastroenteritis was attributed to a lack of proper sewage treatment in the Cree communities. More commonly, the day-to-day underfunding of housing and schools stunted economic progress.

The Cree, working with the Inuit and southern activists, scored one political victory during this period when in 1994 they compelled the province to suspend plans to dam the Great Whale River near the Cree town of Whapmagoostui. Significantly, this success was won not by litigation but through protest, following on the heels of a campaign to convince the northeastern U.S. states that buy surplus energy from Hydro-Québec to consider a boycott.

The elected Cree government, which had arisen out of the ad hoc organizations that fought for Cree rights in the 1970s, took an approach that was at times assertive and at times conciliatory towards future hydro development.

Finally, in 2001, the Quebec government offered to stabilize the disputed funding at a rate of $70 million a year. The proposal was tabled as part of a package agreement known as the Paix des Braves.

In a separate section of the document, the Cree were asked to endorse Hydro-Québec’s proposal to construct four dams on the Rupert River and its tributaries. The project would reduce the Rupert’s flow by 71 per cent at the diversion point, affecting the villages of Nemaska (population 700), and Waskaganish (pop. 2,200), located near the river’s estuary.

In a process honed by the Cree leadership, Cree citizens were then invited to say yes or no, through a referendum question, to the entire agreement — which included the diversion of the Rupert River.

As an added incentive, the province committed, partway through the referendum campaign, to scrap existing plans to dam two smaller rivers that run adjacent to the Rupert, provided that the Rupert diversion went ahead.

Because the earlier project would have flooded 8,000 square kilometres of territory, compared to 640 for just the Rupert, Cree leaders were able to present the province’s standdown as a victory.

To dissenters such as Roger Orr, however, it would have been both preferable and possible for the Cree to turn their backs on the province’s offer, and to meet their financial needs through other investments.

“We’re very dependent people,” says Orr. His voice rings with frustration. “If we say no, that’ll give us the perfect opportunity to start doing things for ourselves, in the way we see fit.

“We talked about the wind energy. We talked about tapping into spring waters, and we talked about ecotourism. We talked about selective forestry and even medicines.”

Orr’s memories from Chisasibi, plus a combative streak, made him a prominent campaigner on the no side in Nemaska.

But for a majority of Cree, the prospect of setting themselves adrift seemed just too daunting.

Also, for most voters, the pattern of past legal setbacks and painful compromise seem to have conditioned a belief that in a winner-takes-all showdown with the utility they would end up the losers.

Walter Jolly, another trapper who lives in Nemaska, puts it succinctly:

“Nobody likes the diversion. [But] if we didn’t agree, they would still go ahead and build those dams.” Much like Freddy Jolly (no relation), Walter has been employed as a construction worker to drill and build on his own trapline. But unlike Freddy, Walter says he supports the project.

“We have to realize that we all can not be trappers or hunters. We have young people growing up. They need jobs.”

With the project now approved, though, jobs in the Cree villages still seem to be in short supply.

Some of the youth I interviewed said they dreamed of being tourist operators, entrepreneurs, or linguists. But as settlement money flows into newly-minted band offices, there seems little hope of building the industry that would sustain this kind of employment.

In Waskaganish, for example, there is a clutch of service industries on the main road, while the regional airport, the band office, and a cottage-size radio station provide other job opportunities.

But aside from settlement money, there are few sources of outside dollars. In the opinion of many, the settlement helps support the community financially without giving it a sense of purpose.

Traditionalists like Freddy Jolly represent a minority whose lifestyle resembles that of the Cree of two generations ago.

Jolly maintains three bush cabins on his trapline, and spends long hours checking his catch and moving from place to place. When he catches a bear (which happens about five times a year) he will sell the fur, and supply meat to his extended family.

By shifting focus from species to species according to the season, Jolly estimates he can make about $1,000 annually in fur sales. Such a lifestyle is necessarily spare, though under the 1975 settlement full-time trappers are eligible for an additional government income subsidy.

But as more woodland is lost to the Rupert diversion (and potentially further hydro projects down the road) it seems inevitable that the place that trapping occupies in the Cree economy will continue to decline.

A typical trapper cabin is equipped with a wood stove, non-perishable food staples, and a two-way radio. A tarp roof filters the light, and makes up for a lack of windows. On both his trapline, and in his house in Nemaska, Jolly drinks tea brewed from the water he hauls from the Rupert, which he says tastes better than the tap variety.

Listening to Freddy describe his childhood and explain his favourite bush recipes, I could sense he felt at home on his trapline in a way that sedentary living could never replace. Still, none of Freddy’s children participated actively in his trade.

Nearly all Cree I spoke to, including youth, spoke of the Rupert diversion as a loss.

Nevertheless, if the hydroelectric debate is framed as tug-of-war between traditions and development, it seems likely that the developmentalists — the self-declared “realists” — will win.

Wind vs. water

In March 2007, as Freddy Jolly was preparing to deforest his trapline, an article on wind energy appeared in Montreal’s independent daily, Le Devoir, discussing a recent development that could have rendered Jolly’s heartbreaking work unnecessary.

Faced with some public criticism for its flooding of forests, Hydro-Québec had previously argued that wind energy is an experimental technology incapable of matching the level of production provided by hydroelectric dams. But according to journalist Louis-Gilles Francoeur, the provincial government had turned down a 2005 offer from a German company, Siemens Wind Power, to construct a wind farm along the banks of an existing reservoir on La Grande River near Chisasibi. The installation, when twinned with another projected wind farm in northeastern Quebec, would have produced electricity on a scale and at a cost comparable to the Rupert River diversion, with far less impact on the Cree in the area.

In his article, Francoeur attributes the province’s refusal to several factors, including a decision to cap wind energy at 10 percent of the utility’s capacity.

For Cree activists, wind power would seem to represent a marriage of choice between development and respect for the land. In a 2006 submission to the environmental review panel that considered and ultimately approved the Rupert diversion, the elected chiefs of Nemaska, Waskaganish and Chisasibi argued forcefully that a wind farm should be built along the shores of an existing hydro-electric reservoir, in Cree territory.

Starting in 1998, Hydro-Québec has connected a small number of wind farms, concentrated mostly in the Atlantic region, into the provincial grid. Wind energy now accounts for about one per cent of capacity and is scheduled to increase somewhat.

Still, questions remain about the scale of the utility’s commitment to new technologies. Shortly after it rejected the Siemens offer, Hydro-Québec announced a competitive bidding process, inviting private contractors to submit proposals to build wind farms and sell the electricity at a predetermined price to the monopoly. A Chisasibi-based Cree contractor, Yudinn Energy Inc., submitted an offer, but did not appear on the list of successful applicants that was released this May.

In a phone interview, Hydro-Québec spokesperson Josée Morin refused to state why the Yudinn offer was not selected. But a look at the company website shows that the Cree proposal was relatively large, boasting a capacity of 324 megawatts, compared to the successful contractors. Out of the 15 proposals selected by Hydro-Québec, 12 were for 150 megawatts or less.

To many observers it seems obvious, as Francoeur’s article suggests, that the province has indeed put a cap on the amount of wind energy it is willing to produce. This attitude appears to have rendered decision-makers intrinsically suspicious of large projects. In public, Hydro-Québec justifies its reservations by stressing that the wind is intermittent, and must be supplemented by energy sources such as hydro that are less weather dependent. But experience from parts of Europe shows that grids which are well integrated can rely on wind for up to 40 per cent of electricity production, averaged over time, without interrupting service.

Compared to this, the 10 per cent limit, as reported by Francoeur, to say nothing of the one per cent capacity that now exists, seems willfully small.

The utility’s engineers, who have built a career, and a subjective identity, around extracting hydro power, may simply not want to tackle the learning curve of doing something different. The Cree chiefs who made a submission to the review panel may have sensed this bias, as they reveal in their statement, which contains more than a tinge of exasperation:

“Having attended many wind industry conferences all over North America over the last few years, we have unfortunately discovered that Hydro-Québec is not a leader but a follower in this 21st-century industry. For many years, Hydro-Québec has been discussing the difficulties of wind development, while others have been busy solving them.” Meanwhile, dams, diversions, and other culturally and environmentally destructive mega projects continue apace.

As long as the rivers run

I left James Bay with about 12 hours of recorded footage: voices of opinions for and against the project, oral histories such as Roger Orr’s, notes to self.

But of those 12 hours I have about 40 seconds of the Rupert River itself.

It was a late April day, with the snowflakes flying, when I asked the driver who was taking me south to Val d’Or to stop at the bridge.

For just under a minute, I stood on the bank as I clicked the button on my recorder, listening to the river, tumultuous and broad as the Upper Saint Lawrence, thunder by me, the flow changing in coloration as it slid over boulders and forged its way over a traditional portage site towards the salt water of the great inland sea.

It was a sad oversight that I waited till the end of my travels to get that recording — and proof, if any were needed, that whatever my attempts at empathy, I was a city journalist and would not easily understand a subjective aspect of the Cree experience that for them was as natural as breathing.

But when the mighty Rupert itself is reduced to a trickle, those voices, and the river recording, will remain. Perhaps then somebody will cue in an old audio file and listen to what was lost.

Chris Scott is a writer, community radio broadcaster and activist who lives in Montreal. He is currently involved in campaigns to protect the Quebec boreal forest and to put an end to Canadian political intervention in Haiti.