Not many in Canada have heard of the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939), and even fewer know of this country’s involvement. The war is lucky to get a footnote in history, overshadowed as it was by the Second World War – the Spanish Republic fell in the first days of spring in 1939, and the Nazis marched into Poland by late summer. But this is not the only reason the civil war remains obscure.

The young Spanish Republic (it was just five years old in 1936) held out the promise of a radically progressive form of democracy, possibly the most radical in the world, if it could only defeat the old order of aristocratic power, capitalist exploitation, and hegemonic Catholicism. The working class in Spain was culturally vibrant and politically engaged, a powerful, revolutionary force. In the civil war, the republic was defended by an unlikely coalition of socialists and anarchists, communists and liberals.

But the republic, in the end, was crushed by the pseudo-fascist armies of Francisco Franco, backed by Hitler and Mussolini. A large portion of the blame rests on the shoulders of the Western democracies, including Canada. Over the course of the war, the democracies refused to do anything to help the republic; indeed, they did a great deal to help sink it, short of openly supporting Franco. This is a black mark on Canada’s national character many would like to forget, and it helps to explain why the Spanish Civil War remains in the shadows of history.

The Mac-Paps

The Mackenzie-Papineau battalion and its volunteer soldiers made their way (often illegally) across Canada, the Atlantic Ocean, and eventually over the French border to “fight fascism” when no one else was yet willing to do so. Among the Mac-Paps were unemployed men and women, communists and anarchists, and recent immigrants – the sort of people rarely treated as heroes, then as now. Over 1,200 men and women from Canada went to fight and die on foreign soil for the freedom of strangers, to be named “legends” for their selfless bravery and dedication by one of the spiritual leaders of the Spanish Republic, the famed communist Dolores Ibárruri.

The Spanish Civil War grabbed headlines in its day as a seemingly clear battle between the forces of democracy and the rising power of fascism. But just as Spain was divided, so was Canada. Michael Petrou, author of Renegades, the definitive work on the volunteers from Canada, says: “in the 1930s, Spain was the cause, more so than other dividing wars, such as Vietnam. Some of the volunteers talked about Spain as a way to get back at the people who were oppressing them in the relief camps. You had immigrants who were envisioning Spain as a chance to avenge losses in the Finnish Civil War for example.” Petrou concludes: “It was almost like a screen on which people could project their aspirations and their hopes and the ideological battles they were fighting out.”

In the heat of the war in the summer of 1937, working-class people in Canada were fundraising to help the Spanish Republic. For the first and only time in their history, the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation and the Communist Party of Canada co-operated by organizing the Canadian Committee to Aid Spanish Democracy. The committee had branches from Vancouver to Halifax that raised tens of thousands of dollars in the midst of the Great Depression.

At the same time, conservatives and liberals saw anything remotely associated with communism as a threat to civilization itself. For many, fascism, on the other hand, looked like an appealing solution to the economic and social crises of the 1930s. The prime minister of Canada himself, William Lyon Mackenzie King, paid a friendly visit to Nazi Germany in the summer of 1937 while the Mac-Paps were defending routes to Madrid.

Writing in his diary, the prime minister expressed fond memories of his meeting with Adolf Hitler: “I then said that I would like to speak once more of the constructive side of his work, and what he was seeking to do for the greater good of those in humble walks of life; that I was strongly in accord with it, and thought it would work; by which he would be remembered; to let nothing destroy that work. I wished him well in his efforts to help mankind.” A month later, his government would pass the Foreign Enlistment Act, which made illegal any effort to help either side in the Spanish Civil War, transparently targeting the volunteers going over to fight for the republic.

A Red doctor

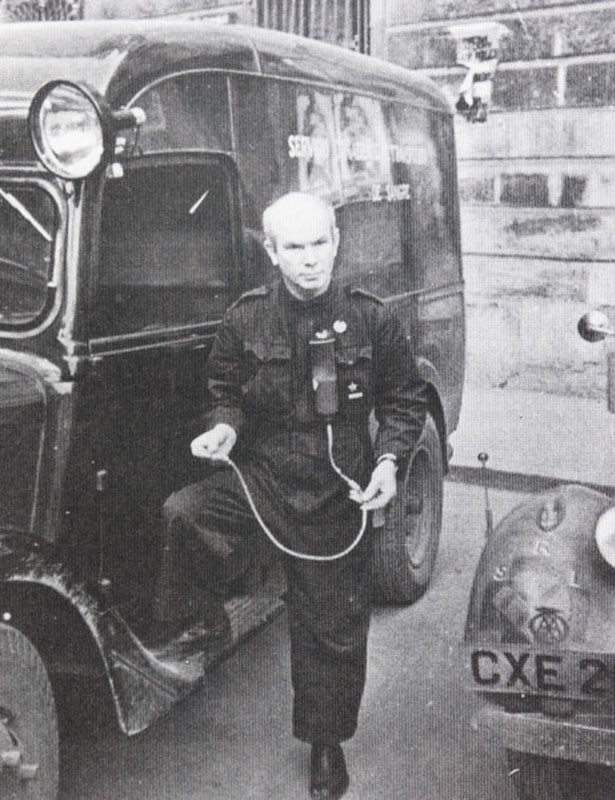

A special clause was inserted into the act to prevent even the humanitarian work of the Canadian mobile blood transfusion unit, a major innovation in battlefield medicine designed by Norman Bethune, one of the first Canadians to go over to Spain in support of the republic. He volunteered to be part of a Canadian-funded hospital unit in October 1936, but when he arrived in Spain, apparently bored with the idea of working too far from the front lines, he pioneered the mobile blood transfusion unit.

Bethune was an anomaly for a Canadian icon: he was outspoken, arrogant, and required adventure. An accomplished thoracic surgeon, Bethune had himself been on the edge of death more than once. He had been wounded by shrapnel when a shell exploded near him during the First World War and had been cured of tuberculosis during the 1920s by undergoing an experimental operation that involved the deliberate collapse of an infected lung.

He became a Communist in the 1930s in reaction to the poverty and repression he witnessed during the Great Depression. The only quality that might have rivalled his intense idealism was his gigantic and restless ego. Born in 1890 in Gravenhurst, ON, Bethune was eulogized by Chairman Mao Zedong after he died of blood poisoning in 1939 while treating Communist Chinese soldiers on the front lines. There are statues in his honour throughout China.

Petrou believes that Bethune’s presence on the side of the Spanish Republic against the conservative-backed Franco had a powerful symbolic effect. “Bethune was a tangible example of international solidarity with the beleaguered Spaniards, especially during the siege of Madrid. In the fall of 1936, the fascists have been unstoppable, they are at the gates of Madrid, the workers have armed themselves, they’ve thrown up these banners [that read] ‘no pasaran’ (‘they shall not pass’) and there’s Bethune, this foreigner, in the middle of this maelstrom, giving Spaniards a way to help people at the front. The act of giving blood is symbolically powerful.”

But with his contentious personality, he quickly alienated Spanish authorities. To make matters worse, a love affair with a Swedish journalist, Kajsa Rothman, suspected of being a fascist spy, made Bethune a suspicious character, and by April 1937 he was an unwelcome presence in the Spanish Republic.

A mission from the Canadian committee was sent out to retrieve Bethune before he caused an international incident. The job was entrusted to Alexander A. MacLeod, a former steelworker from Nova Scotia who had converted to communism, a charismatic organizer with movie-star looks. MacLeod was an exceptional Communist leader.

President of the Canadian League Against War and Fascism (a vehicle for promoting the Popular Front and Soviet interests), he later became one of only two Communists to sit in the Ontario Legislative Assembly as the MPP for Toronto’s Bellwoods in the 1940s and ’50s. As testament to his powers of persuasion, MacLeod would convince R.B. Bennett, arch-conservative and former prime minister, to donate $500 to help repatriate the Mac-Paps at the war’s end in 1939, when funds were scarce.

Children’s villages

When MacLeod caught up to Bethune in war-torn Spain in the early summer of 1937, the doctor had already resigned from his post but was dreaming up new ideas to help the Spanish cause. Having witnessed the horrors the civilian population had suffered along the battlefront, especially children, Bethune sketched out the idea of building children’s villages to house orphans and child refugees in the relative serenity of Catalonia, far from the front. Bethune argued that such a project would inspire renewed support for the republic in Canada.

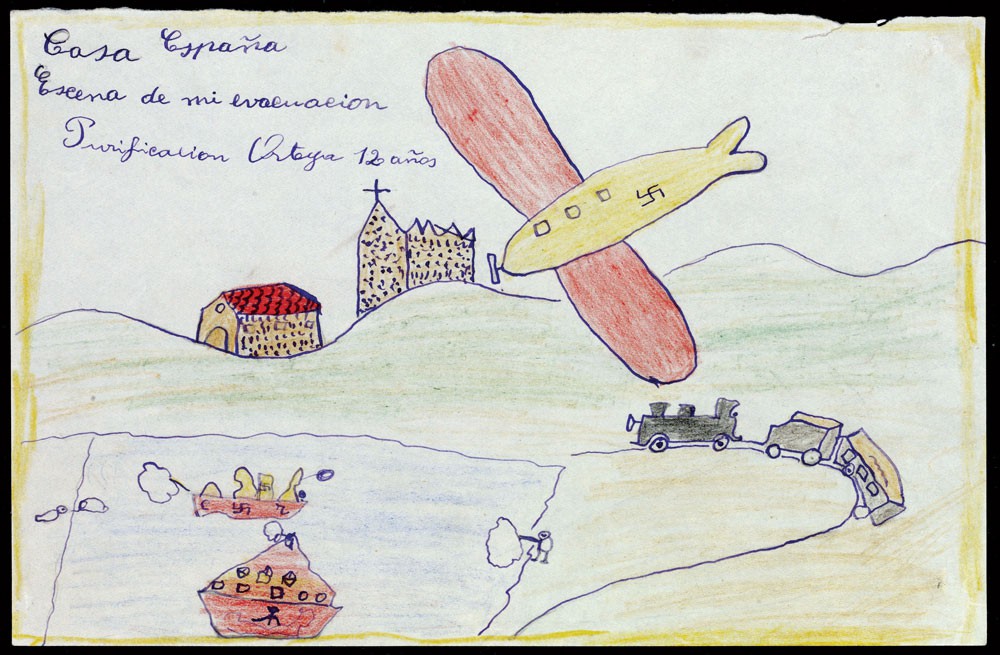

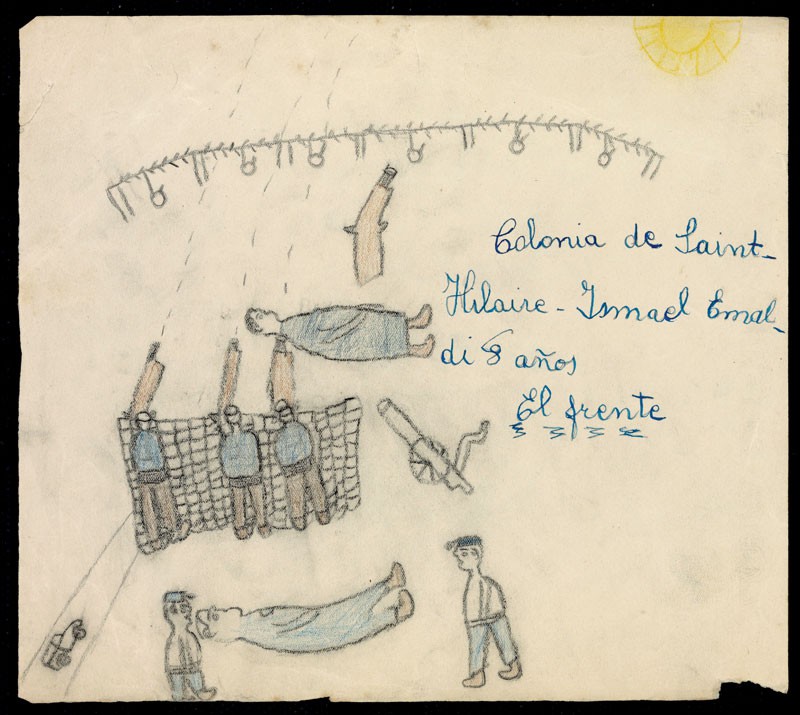

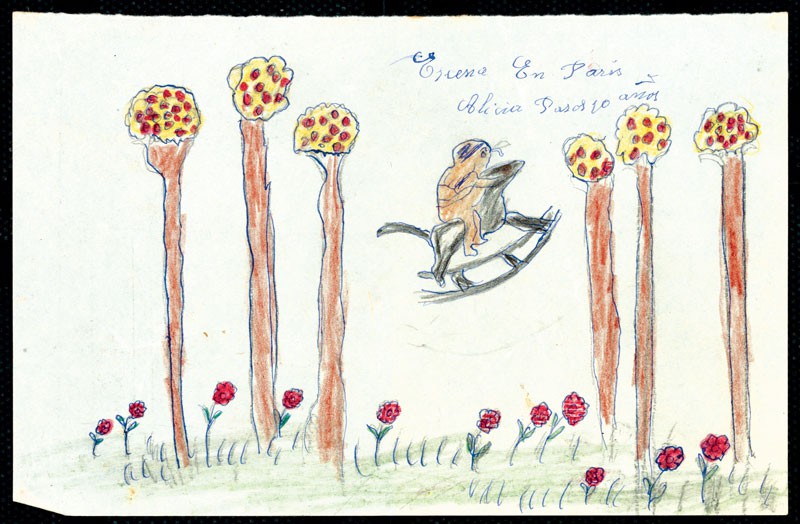

MacLeod liked the plan, but knowing Bethune’s time was up in Spain, he convinced him he could best make the plan happen by going on a speaking tour in Canada to rally support for it. MacLeod continued on his journey through Spain, giving speeches, meeting with officials, and paying visits to children’s colonies already set up by the Republic. It was during these visits that he took with him dozens of drawings made by child refugees of their wartime experiences, of evacuations, of battles and destroyed towns, of life in the colonies.

Back in Canada, the drawings made great propaganda for the republican cause, demonstrating better than any speech the strangeness and sadness of war. The pictures became mainstays at meetings of the Committee to Aid Spanish Democracy, and they became especially potent after the aerial bombing of the town of Guernica in April 1937 by Hitler’s Condor Legion, which left hundreds of civilians dead. The bombing made international headlines and shifted public opinion in Canada in support of the republic. Pablo Picasso’s painting of the Guernica atrocity became world famous in the summer of 1937, and its simple, raw, and almost childlike images of destruction echoed the scenes of war as depicted by the refugee children that MacLeod had met and championed.

MacLeod pitched the idea of children’s colonies to the executive of the Canadian committee and got them to agree to commission the creation of two centres outside of Barcelona which together would shelter 150 children. One was established at a former convent renamed the Salem Bland House, after the progressive Methodist minister from Toronto. The other, in the abandoned mansion of a pro-Franco nobleman, was called The Pines.

Money from supporters in Canada continued to aid the “adopted” children even after they were evacuated from Salem Bland House and moved to refugee camps in France at the end of the war. The effort helped expand the appeal of supporting the Spanish Republic outside the circles of left-wing politics. One of the committee’s pamphlets asking for support for the centres read: “there is no reservation to religion, creed or political opinion in the declaration ‘Inasmuch as ye have done it unto one of the least of these, my brethren, ye have done it unto Me.’ ”

The pictures MacLeod brought back also later aided a Milk for Spain campaign, which inspired an incredible amount of donations given the hard times most in Canada were living through. In the summer of 1937, when the prime minister of Canada spent his time admiring the “constructive” work of Adolf Hitler, others were moved by the ominous messages in the Spanish children’s drawings.

The governing parties in Canada of the 1930s saw social activists, trade unionists, and political agitators as threats to their legitimacy and the rise of fascism as a protective shield against working-class radicalism. It was as true back then as it was when Stephen Harper declared that Canada “has no history of colonialism” while presiding over the destitution and occupation of Indigenous nations, from Attawapiskat to Elsipogtog. Is it a stretch to connect the defence of the working class in Spain, against capitalism and fascism, to uprisings like the Arab Spring, anti-austerity movements across the globe, or struggles for self-determination from Canada to Palestine?