I am often conflicted as an educator. As a Native woman, I consider the current system of education in Canada to be inherently colonial, and I hate my role in perpetuating it.

Many Native people have negative feelings toward the education system, and for good reason. It was one of the main tools of what I call annihilationist policies toward us. (I think the term “assimilationist” is too mild for what was intended.) It continues to be a place where we are forgotten, or actively belittled, as peoples. But the negativity also comes from an awareness that Indigenous ways of knowing are ignored completely by the educational system. We can have all the “Aboriginal content” you can shake a stick at, but ultimately, Indigenous peoples do not pass on our wisdom in this way.

As a Native mother, I want my children to have an Indigenous education. But an Indigenous education is not valued in Canadian society. If I focus all my energy on providing my children with as much of an Indigenous education as possible, I will still have to ensure they succeed in Canadian schools or I will be setting them up for failure. And failure for us is not being unable to be a doctor or an astronaut. It means marginalization, poverty, suicide, death. I cannot allow that to happen.

The reality of our situation is that unless we succeed in Canadian schools, we will never be able to revive Indigenous education. We will never have the capacity to bring back into being a fundamentally different way of learning about the world. We have already been losing pieces, and eventually there will be nothing more to lose.

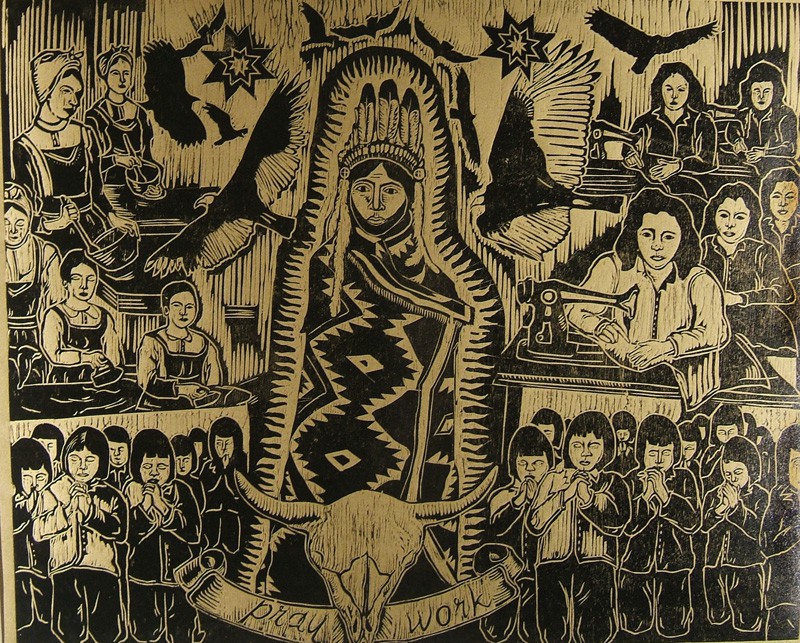

What is required is nothing short of superhuman effort. Not only do we have to excel in a foreign system of education, we must do so without sacrificing ourselves, without succumbing to annihilation. At the same time, we must root ourselves in traditional pedagogy. We have to do it all.

Right now, many of our communities are in conflict. They want Indigenous education, not “education for Indigenous peoples,” which is merely Canadian education with cut-and-pasted medicine wheels or four direction teachings. We often don’t buy into Canadian schools, even when they’re run by the local band. Knowing that we are not going to be validated, or celebrated, or sometimes even discussed at all, means that we have little incentive. Sometimes we believe that lack of success in Canadian systems means we are more Indigenous, less colonized. We want the system to fail because maybe then it will finally be understood that the system has been failing us all along.

We don’t have the capacity yet to create our own educational systems in a way that allows us to send our children out into the world prepared for a reality that places European values above all others. My eldest daughter is almost 11. She can’t wait for that capacity to be developed down the road. But she’s got to do her best with what exists now.

Idle No More is calling on its superheroes. Rather than waiting for some magical time when Canadians recognize that our ways of knowing are valuable, as though suddenly the “bush PhDs” among us will finally get noticed, we need to first ensure that we value those ways of knowing ourselves. That means doing the difficult work of reclaiming Indigenous pedagogies.

We all have an important role to play. Whether we are setting up language nests in our living rooms or taking kids and parents out on the land, we need to be doing more of it. We must all become students of our own cultures and dedicate ourselves to learning for the sake of our children and grandchildren.

At the same time, we should be supporting our children to excel in the Canadian system. It isn’t fair and it isn’t right, but it needs doing. Our peoples have shown themselves to be masters at integrating new technologies and adapting to new situations without losing their core values. Shifting our expectations so that we create a support system for our children to succeed in Canadian schools and in traditional settings is how we are going to build this capacity. We need to buy in, while remembering that Canadian education is nothing more than a means to an end.

So let us kick out the substandard teachers and the administrators who do not believe in our kids. Let us bring the parents and the whole community into the classroom. Let us expect more of our kids. Let us expect more of ourselves. Let us expect superhuman effort, knowing we can absolutely rise to the occasion but that we cannot do it alone. We cannot let our hopes for the future blind us to the work we have to do right now.