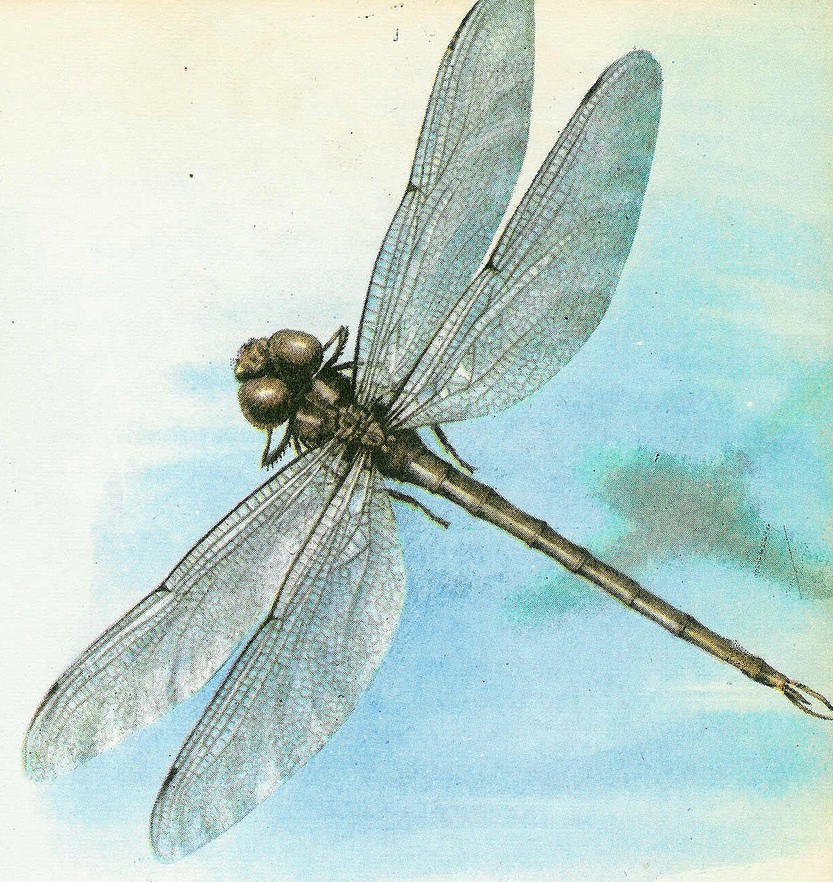

The spring had been wet and the summer hot and it had been a bad year for mosquitoes. After the water dried up and the mosquitoes died off, the dragonflies appeared. So, as I sat with my wife at the admissions desk of the hospital for my upcoming operation, I was not surprised to see a large dragonfly come through the front entrance and land on the glass between the clerk and me. I was watching it flex its metallic green wings against its long abdomen, when I realized that the clerk was staring at me. It had been two hours since I had taken an Ativan to numb and relieve me of any anxieties over the procedure.

“His name is Oliver Adler,” said my wife Christine.

I looked at her, thankful she was there.

“Did you see the dragonfly?” I asked.

I pointed but it had already gone.

I turned back to the clerk and I had to squint my eyes to focus. He looked at his screen.

“Alder?”

“No, Adler. A-D-L-E-R.”

“Right. Do you know where you’re going?”

Evidently, the clerk had given up on me and had decided to speak only to my wife. I looked at her and saw that the dragonfly had landed on her head, like a viridescent bow that my daughter would use in her hair. Viridescent—I liked the sound of the word as it wobbled in my brain.

I reached out to pet the dragonfly but it moved around to the back of Christine’s head. My wife stared at me.

I mumbled, “Dragonfly.”

I think it was at that moment that she gave up on me as well.

“Go down that hall. Take the stairs to the third floor. Turn left and go in the door that says ‘vasectomies’.”

I tried to say thank you, to show the clerk that I was all right, but he had already moved on to the next admission.

I kept up with my wife all the way to the third floor and turned left, giving a little sprint to reach the door before her. I made sure to open it courteously and let her enter first. She didn’t seem to appreciate it. We seated ourselves in the middle of the room.

A woman near my wife was yelling into her cell phone at someone. I looked at my wife and whispered, “Whoever she’s talking to already had his balls cut off.” Judging by my wife’s reaction, I may not have been as quiet as I thought.

I tried to recover. “I don’t think this Ativan is affecting me too much.”

“You don’t?”

I chewed on my tongue. In my youth, I had discovered that this was the quickest way to know if I was drunk. I couldn’t feel it so I decided to cover.

“Well, I am definitely not like dad.” I felt the qualifier was important to emphasize. At nights, after the Alzheimer’s had taken his mind, my dad’s care nurses had tried to sedate him with Ativan but he’d had an adverse reaction to it. Instead of settling him down, it cranked his mind to high. One night in the middle of winter, he escaped, breaking a wheelchair and going out a back door. He set off the only alarm in the place but the nurses never caught him. It was a baker heading to work who found him on the other side of town, freezing, dressed only in his hospital gown, and brought him back.

“Are you sure you’re not like him?” Christine asked.

“Of course I am. Why wouldn’t I be?” I knew I was supposed to take offense to her suggestion but I couldn’t figure out why.

A nurse looked up from her desk, “Oliver Alder?”

My wife answered, “Adler.”

The nurse looked at her sheet, “Oh, right. Come along.”

I followed the nurse into an airy hallway with two curtained-off areas. She waved to the one that was open, where a hospital bed sat with its upper back cranked to a 45-degree angle.

“You can put your pants on the chair, climb onto the bed, and pull the sheet over you.”

Before dad had been sick, Christine and I had backpacked with the kids through France, Italy, and Greece and I learned to appreciate the easygoing European attitude about the human body. I would later tell my wife that it was this appreciation and nothing else that prompted me to disrobe in front of the nurse. The nurse turned, unimpressed, and closed the curtain. I hoped that her disdain for me was for no other reason than she had seen enough naked patients to last a lifetime.

I was relaxing on the bed when the doctor entered the room. “Hello, Mr. Alder.”

I didn’t correct him.

“I have a resident helping me out today. We’ll prep you until he arrives.”

It is said that men who have vasectomies have a lower chance of prostate cancer, not because of the operation itself but because any problems are likely to be detected early, thanks to their willingness to let a doctor touch the family jewels. Lying there, half undressed, watching the doctor prepare his needle for freezing, I wondered how low the statistics for prostate cancer in European men were.

“All you are going to feel is a little tug.” I watched as the needle went under my skin. The lower part of my body felt very far away and my head was trying to remember a Bette Midler movie where the doctor gave a pregnant woman a needle and said, “All you’ll feel is a little prick” and the woman responded, “That’s what got me here in the first place.” Before I figured out the title, I realized the doctor had left the room.

“Mr. Alder?”

I opened my eyes to find the doctor staring at me. I had been dreaming of dragonflies, filling the brightening sky and stretching their wings in the early morning sun.

“I’d like you to meet Dr. Adler.” The resident stood behind the doctor, his humped back turned towards me. I laughed out loud at the similarity of our names but I couldn’t remember if I opened my mouth.

The resident turned and it was my father, looking like he did the night of his viewing at the funeral home. His hair was long and white and his cheeks had been filled in with cotton. His skin was waxy and he looked stiff and formal. He was wearing his suit under the scrubs. The life was back in his eyes and when he smiled, I could feel he recognized me.

The doctor punctured my scrotum with a hemostat. He drew the first tube out of the hole and clipped it off.

“Shit, I hate hospitals,” my father grouched. I couldn’t agree with him more.

The doctor sewed up the first tube. “It’s bleeding a little. Let’s clean it up.”

My dad handed the doctor what looked like a soldering iron. There was a little hiss and smell as the wound was cauterized. The doctor pulled out the second tube and he looked to my dad.

“I’ll get you to do this one.” He pinched off the tube and handed my dad the snips. My father took them in his hand and looked at me. He and I stared at each other. Before this operation, before the funeral, before the Alzheimer’s, life had been a steady course without change.

“There are some things we should never have to do.”

I was sure he said more but my mind fell backwards and by the time he had snipped and stitched and sutured me, I was looking up at him from the other side of a thick glass. On the ride home, Christine said I mumbled about not wanting my mouth sewn shut for telling a lie. She said I slept four hours. But I never did. I waited and I hid and I never told her what had happened, how I had seen my father, or when I had reached out for his hand, he had stepped away. Finally, I never told her that he had shed his doctor’s robe, and stretched out his four magnificent viridescent wings, flexing them and then, without a goodbye, he had flown up through the roof of the hospital and escaped into the warm morning sun.

_780_520_90_s_c1.jpg)