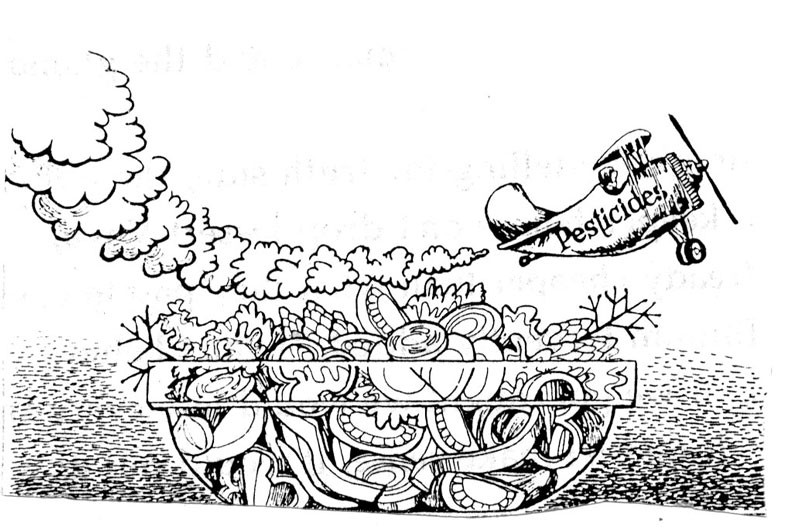

If you are like most people, you don’t wonder much about the foods you pick up at the supermarket. You trust that they’re as straightforward as meat and potatoes, and nothing you’re going to find on the labels is likely to change that. You won’t read, for instance, that the steak you choose for the barbecue was cut from a cow that was raised in a “concentrated animal feeding operation” where it was routinely treated with antibiotics and insecticides to prevent the spread of disease in the tight quarters in which it lived alongside over 1,000 others; or that the “heart-healthy” canola oil in which you like to fry the potatoes is made from seed that has been genetically engineered to tolerate high doses of pesticides.

Health Canada recognizes that consumers must be provided with the information necessary to make healthy food choices. The Food and Drugs Act therefore requires that the ingredients and nutritional profile of packaged foods be labelled. But because healthy foods are more than the sum of their parts – they are only “healthy” if they are sustainably produced too – I think it is time we expand the legislation governing food labelling to provide consumers with information about not only what is in their food but also how it is produced.

Start with breakfast. I want to know where and how my orange juice was processed; what’s been done to the corn in my bowl of cereal; what’s in the milk I pour over it; whether the rights of the person who picked the banana I slice on top are respected; how the chickens that laid the eggs I scrambled are raised. If we knew more about how our food was produced, many of us would choose to eat differently. That’s why I’ve made it my mission to make information about how our food is produced more easily available.

The problem is that when I tell people I’m a food activist fighting for “a community right to know how food is produced,” I get a lot of blank stares. My colleagues think it is my choice of words. The “community right to know,” they tell me, is a legalistic concept that’s not part of everyday vocabulary. True, but I if I said I was trying to strengthen our right to know about the toxic pollutants in our environment, no doubt people would react differently. They would probably say, good for you, that’s important.

Which brings me to my explanation for the confusion over my job description: the concept of the community right to know is familiar, but only within a specific context. We hear about it most often in association with practices that endanger our health. This connection makes sense. It is easy to understand why we need a right to know about the existence of harmful chemicals in our immediate environment.

Only when another bout of salmonella or E. coli breaks out do we tend to think of information about how our food is produced as critical to our health and safety. Hazard prevention and the community-right-to-know principle have become so intertwined that speaking about that right in relation to something as seemingly benign as growing apples or raising cattle challenges our notion of the right as a device to protect ourselves from life-threatening activity.

I now realize that sparking a movement for the right to know how food is produced must begin by reframing the right to know as more than a safety measure. There are many reasons we should have a right to know how our food is produced and not all of them involve protecting ourselves from clear and present danger. I don’t want to eat meat that comes from animals that were treated inhumanely, or fruit and vegetables picked by farm labourers who are denied their basic rights. I am advocating for a right to know how our meat, potatoes and other food staples are produced so that we can make choices that are consistent with our convictions and that promote a more inclusive concept of health.

With a little bit of imagination, and the media’s growing attention to how our food reaches the table, hopefully soon this life pursuit will not be so hard to explain.

Alissa Hamilton is a Woodcock-Foundation-funded Food and Society Policy Fellow and the author of the forthcoming book Squeezed: What You Don’t Know About Orange Juice (Yale University Press), due out in May 2009. She lives in Toronto.