Canada’s Deadly Secret: Saskatchewan Uranium and the Global Nuclear System

Jim Harding

Fernwood, 2007

The nuclear industry has seized upon rising energy prices and growing concerns about global warming as an opportunity to market nuclear energy as a clean, green alternative to oil, gas and coal. But citizens’ groups across the country know that nuclear means neither clean nor green, and are working to counter the nuclear lobby’s propaganda. A useful tool for these groups is Jim Harding’s new book, Canada’s Deadly Secret: Saskatchewan Uranium and the Global Nuclear System.

In Canada’s Deadly Secret, Harding charts the development of the nuclear industry in Canada (especially Saskatchewan) over the past half-century. The book is a challenging read, in part because Harding’s academic background (he is a retired professor of environmental and justice studies) is so evident in the writing. The larger challenge for readers, however, is in facing the ugly truth that Canada, and in particular Saskatchewan, has played a prominent role in the global nuclear system. Nevertheless, Harding’s book remains an invaluable read. It brings to light information that has been buried or misrepresented by proponents of the industry, the government and the corporate media. It is a call for those who love the earth to unite for a sustainable future.

To build his case for powering down the Canadian nuclear industry, Harding refers to the 1987 report of the Brundtland Commission, which states, “[n]o technology, nuclear or otherwise, without a proven waste management system should be developed in the first place.” The commission, headed by then-Norwegian Prime Minister and former environment minister Gro Harlem Brundtland, presented a global agenda for change in response to the United Nations General Assembly’s urgent call for action on environmental issues. Nuclear proponents including the governments of Canada and Saskatchewan, in their short-sightedness, continue to ignore the serious challenges raised by the report.

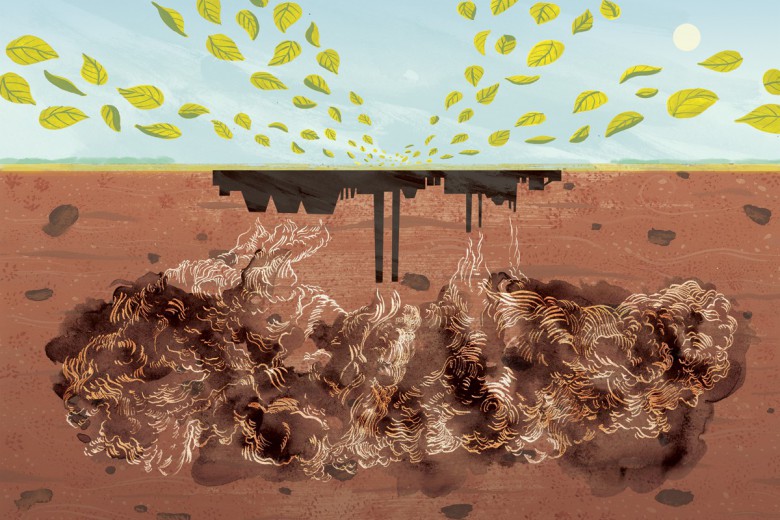

The global nuclear system has “continually failed to fulfill its guarantee of a waste storage system,” says Harding. As a result, he suggests, “the only socially and ecologically responsible thing to do is to immediately stop using the technology, thus preventing a buildup of even more nuclear wastes.”

Although Canada is a signatory to the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, we continue to supply the United States with high-grade uranium ore (the treaty forbids uranium sales when its end use is weaponry). Harding shows that “upwards of one-third and perhaps more of the U.S. stockpile used for [depleted uranium] and nuclear weaponry comes from Canada, with most of this from Saskatchewan due to the high exports in recent decades.”

The global nuclear system has generated vast amounts of incredibly dangerous waste products like plutonium. Plutonium, says Harding, is “one of the most toxic threats to future ecosystems and inhabitants.” Its half-life is 24,000 years. After doing the math, Harding concludes that “even after a quarter of a million years of radioactive decay, a tonne of plutonium would still remain as a kilogram of plutonium which, if dispensed, would still be enough to poison a billion people.”

Though Harding’s book exposes the nuclear system’s narrative as a dangerous fantasy, all is not doom and gloom. Harding points out that strong movements to shut down the industry have emerged in the past. In the 1980s such movements were partly successful—in Saskatchewan, particularly. Activists stopped the development of a nuclear refinery in Warman, Saskatchewan, but have been unable to stop the mining of uranium in the province. Still, groups are currently reorganizing to stop the current push for the development of a reactor in Saskatchewan.

Another positive development Harding points out is that despite millions of dollars in corporate welfare provided to the nuclear industry by governments around the world, “renewable energy has now passed nuclear as a source of electricity (20 per cent to 17 per cent).” He explains, “This is partly due to wind, biomass and solar power, but is mostly due to cogeneration of electricity from waste heat. Wave (tidal) power will soon accelerate this trend.” Alternatives to the nuclear system are thriving.

Harding’s courageous and forthright exposure of the deadly secrets that governments and the industry continue to hide will surely help us to overcome our nuclear amnesia and build a popular movement capable of ending Canada’s active participation in the global nuclear system.