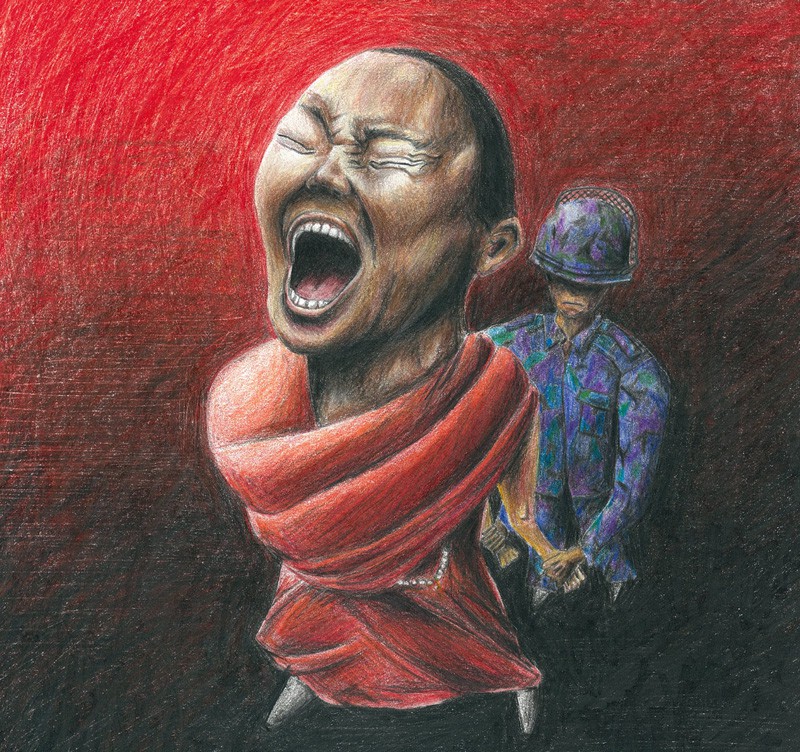

Spiritual belief can be a potent political force. It can be wielded as a tool of oppression, and can also offer a wellspring of strength to people resisting oppression at the risk of violence and death. The sense of a reality greater than our individual selves, and the belief in a spirit that transcends the horrors and sorrows of the world around us, can spark courage, loyalty and hope in conditions where these might otherwise wither. This is particularly evident in the Tibetan independence movement, in which Buddhism has played a major role in the resistance to the totalitarian rule of the People’s Republic of China.

Tibetan Buddhism’s heavy emphasis on virtues of non-violence and compassion for all living beings raises the complex question of if or when to use violence against a violent occupier.

The 2008 Uprising

In 2008, Tibet was rocked by the most widespread series of demonstrations for independence since the occupation of Tibet began in 1950 (for a brief overview of the Chinese occupation of Tibet, click here). Notably, monks and nuns were often leading the protests and bore the brunt of Chinese repression.

The Chinese government made much of Tibetan violence in the early days of rioting in order to justify its harsh security measures. Images of Tibetans attacking Chinese civilians and smashing shop windows were surprising to many, as the Dalai Lama’s policy of non-violence and diplomacy has come to define the Tibetan struggle in the eyes of the international community.

Initially, the 2008 protests were non-violent, with reports of Tibetan monks, nuns and laypeople defiantly flying Tibetan flags in place of the Chinese flag. Protests began to spread following sieges of the three largest monasteries in the Tibetan capital of Lhasa, and continued for several days amidst mass arrests by Chinese security forces before rioting erupted on March 14, 2008.

When riots broke out in Lhasa, they were initially reported to have been triggered by the ethnic resentment of Tibetans towards Han Chinese immigrants. But the real story behind the turn to violence, as reported by Al-Jazeera and the Guardian, was the mass arrests by Chinese police of protesters demonstrating peacefully in support of Tibetan independence for nearly a week prior.

The Chinese government predictably accused the exiled Dalai Lama of orchestrating the riots as part of a separatist plot and of attempting to sabotage the Beijing Olympics. A week into the rioting (and subsequent crackdown by Chinese authorities), the Dalai Lama publicly condemned the violence, urged both Chinese and Tibetan people to refrain from harming each other, and threatened to resign from his position as temporal leader of Tibet if the violence continued. Although protests continued for several days, they were reportedly peaceful in the face of brutal repression. Chinese authorities continued to carry out thousands of arrests, rounding up the populations of entire monasteries, and barring foreigners — including journalists — from entering Tibet.

According to Dermod Travis of the Canada Tibet Committee, “What was notable about the 2008 uprising, is the fact that not all protests were centered in Lhasa and that they spread into very rural areas of Tibet” In that sense it was much more of a general popular uprising” [and] a more worrisome uprising for the government of China simply because it was not isolated to one community.”

The Dalai Lama’s Middle Way

2008 was not the first time the Dalai Lama had denounced violent resistance by Tibetans. In 1974, he publicly condemned the work of Chushi Gangdruk, a Tibetan guerrilla army formed in the early 1950s in response to China’s increasingly oppressive regime. The Chushi Gangdruk saw themselves as protectors of a Buddhist culture that could not fight in its own defence because of its spiritual emphasis on non-violence. When, at the behest of the Indian government (which needed to reduce tensions with China), the Dalai Lama issued a public statement encouraging the Tibetan guerrillas to give up violence, his message was met with great dismay among the fighters. Many of them deserted immediately, and some reportedly committed suicide over the news.

The 14th Dalai Lama’s current Middle Way policy advocates for cultural autonomy from China while accepting Chinese sovereignty over Tibet, and rejects violence as a political tool. But conflicting interpretations of non-violence in an atmosphere of violent oppression by Chinese authorities have caused some to question the efficacy of this Dalai Lama’s methods. Jamyang Norbu, a Tibetan writer and activist who at one time served in the Chushi Gangdruk, told Briarpatch that “the whole idea of non-violence in resistance to the Chinese” is a fairly recent thing. It’s something that this Dalai Lama actually has conjured up, because the 13th Dalai Lama” even created a modern army. He wanted Tibetans to resist. You have to resist initially peacefully, but when there are no other recourses, you have to resist violently.”

Norbu voices the feelings of a number of Tibetans who identify as Buddhist and by and large accept the Dalai Lama’s leadership, but who do not subscribe to the Middle Way strategy. Among them is the Bod Rangzen (Independent Tibet) movement, which rejects the Dalai Lama’s compromise of accepting Chinese authority and sees the occupation as fundamentally illegitimate.

The day after the Dalai Lama called for an end to the violence in 2008, Zhang Qingli, secretary of Tibet’s Communist Party, told the Tibet Daily that “The Dalai is a wolf in monk’s robes, a devil with a human face but the heart of a beast” and that “we are now engaged in a fierce blood-and-fire battle with the Dalai clique, a life-and-death battle between us and the enemy.” Apart from prominent Communist leaders such as Zhang Qingli, many in the resistance movement have come to question the effectiveness of the Buddhist precept of non-violence as policy.

Diverse tactics

Violence is not new to the Tibetan struggle, which has employed diverse tactics ranging from civil disobedience to guerrilla warfare. The Chushi Gangdruk guerrilla army survived for nearly 20 years, from the 1950s to the 1970s, scoring some remarkable successes against the overwhelming numbers and resources of the Chinese army. Composed mainly of fighters from the Kham region of Tibet, the Chushi Gangruk received training and equipment from the CIA to engage in armed conflict with the People’s Liberation Army. To this day, their veterans take great pride in their critical role in protecting the Dalai Lama and escorting him to India during his dramatic escape in 1959, and do not see a contradiction in their veneration of Buddhism and the violent means they have employed to protect it.

Despite being a major target of the Chinese government, monasteries are also a breeding ground for resistance of a different sort. According to Dermod Travis of the Canada Tibet Committee, “the monasteries” act as a place where people” share thoughts and share opinions and strategies.”

Among the most emblematic of these strategies is self-immolation, in which monks have set themselves on fire as an expression of the horror of Chinese oppression. On Feb. 27, 2009, a young monk known only as Tabey set himself on fire while holding a picture of the Dalai Lama in eastern Tibet. He was reportedly shot by Chinese police and taken away. It has never been determined if and when he died thereafter. Thupten Ngodup, a Tibetan monk, died after self-immolating during a police raid on hunger strikers in Delhi in 1998, and it is audible on the video recording of the incident that he was crying out “Bod Rangzen” and “Long live the Dalai Lama” while he danced on fire in the midst of a crowd of police and protesters.

The monkhood is also known for other, less heart-rending but equally powerful forms of resistance, including acts of civil disobedience in defiance of the practice of “re-education” by Chinese security forces, whereby individuals are tortured and intimidated into renouncing their beliefs and sacred figures. This is often accomplished through the technique of “self-criticism” of confessing one’s alleged heresies and affirming Communist ideology as dictated by the Chinese government. This might involve writing out standard statements of confession, or verbally rejecting the “Dalai clique.” Chinese dissident and writer Lixiong recounts stories of monks turning the paper on which they were told to write their condemnations of the Dalai Lama into paper airplanes and sailing them about the room, or, more commonly, making slight changes to the phrasing of their written condemnations to subvert their meaning. The difference between the characters for “is” and “is not” in the Tibetan language is only a dot, so all it takes is the slightest of dots to turn “The Dalai Lama is the head of a separatist clique” to “The Dalai Lama is not the head of a separatist clique.”

Among lay people, apart from overt public forms of resistance such as demonstrations, which could result in imprisonment, torture or death, Travis points to a new tactic being used in Tibet called “White Wednesdays” as an example of non-violent resistance taking place outside of the Buddhist institutions. Originally, Travis explains, White Wednesday meant wearing white to commemorate the Dalai Lama’s birth date, but since 2008 Tibetans within Tibet have been pledging to “find unique ways of demonstrating their Tibetan spirit” more regularly. “One tactic may be that on a particular Wednesday we will only speak Tibetan” If somebody who is Chinese speaks to us, we will only reply in Tibetan” explains Travis.

‘Sticking it out like the Buddha’

The military force of the world’s emerging superpower is not one that can be easily overthrown by guerrillas, nor dissuaded from tyranny by noble teaching or reasoned diplomacy. In this context, Tibetan Buddhism provides more than just meagre comfort in a tragic world: it also provides a source of courage.

According to Jamyang Norbu, “Buddhism is not just about peace. A Buddhist is not just a pacifist, going around telling people “˜you mustn’t hurt people’ all the time — that was not the primary objective. I think [Buddha’s] primary objective was to find the truth. I think Tibetans have to look at their cause in that way, not by some kind of pacifist ideology, but to look at the issue as it is.”

“I believe in the Buddha in some ways as a warrior” he continued. “He came from a warrior past in India, and… sitting under that tree, [Buddha said] “˜I’m going to sit here, even if I’m going to die, whatever happens to me, I’m going to sit here until I’ve worked this damn thing out in my head: enlightenment.’ We Tibetans should be able to just say, “˜I’m not doing this Tibetan independence thing only for myself, I’m doing it really not only for Tibetans in some ways, but for the war for justice in this world, and I’m sticking it out like the Buddha.’”