“It’s been my dream since I was seven years old,” Zeke Deas tells me as we walk around his large rural property. “Since then I’ve wanted to have a nice piece of land and raise horses.” He shows me the area, covered in large, round hay bales, that he now rents out to be farmed. From there, we have a great view of the property and his house in the distance. He points out the area where his horses, now long gone, used to roam.

Deas is one of the few Black farm owners in Grey County, Ontario. He’s lived here for 55 years and says that the Black history of the area is what he loves and feels most connected to. He didn’t inherit his property or know the local Black backstory before he bought it, but “for some reason, I felt a strong pull toward coming here,” he tells me. “I couldn’t say what it was. Fate, most likely.”

Deas defies one of Canada’s most deeply rooted stereotypes: that rural Canada is white.

He tells me how much he loves the natural beauty of his property, explaining that the land is what brings him comfort when he experiences racism. Overall, he’s had good experiences living in the area, but he notes that rural racism is “two-faced”: neighbours might be polite to you in person and then degrade you behind your back.

Deas defies one of Canada’s most deeply rooted stereotypes: that rural Canada is white. Indeed, across North America, the very word “urban” is associated with Black culture. At times, it’s used by Black artists to describe their own work; other times it’s a racist dog whistle used by politicians keen on “revitalizing (read: gentrifying) urban communities.”

It’s true that most Black people in Canada live in cities. In 2016, 94.3 per cent of Black Canadians lived in the country’s census metropolitan areas, in comparison to 71.2 per cent of Canada’s total population. But plenty, like Deas, also call rural Canada home and even more have important ties to these spaces.

Deas’s comment about the nature of rural racism touches on another Canadian stereotype: that of the polite, tolerant Canadian. It’s a myth that’s strongest in rural Canada. White people in rural areas are imagined as warm, generous, and welcoming – and racist. The apparent contradiction is explained away: white rural Canadians aren’t malicious; they just don’t know any Black people, Indigenous people, or people of colour. And how can they, when rural Canada is so white?

As with all racism, interpersonal incidents hint at much greater systemic issues. When we fail to talk about rural Black Canadians, we contribute to the erasure of Black history, present, and future.

Rewriting Canadian history

The myth of Canadian tolerance toward Black people is due, at least in part, to two historical events – both of which have been rewritten to serve Canadian nationalism.

First, in the late 1700s, around 3,500 Black Loyalists who fought on the side of the British during the American Revolutionary War were given land in Nova Scotia and other parts of the Maritimes as a reward for their service to the British Crown. Black Loyalists serving in the War of 1812 were similarly given land in what’s now Ontario.

Second, in the early to mid-1800s, Canada marked the final destination for many risking their lives to escape enslavement through the Underground Railroad, and Canada was framed as a colony with ample land for farming where Black people could live new, free lives. These accounts of Canadian history conceal the colonial and anti-Black impulses underpinning Black immigration into Canada.

When talking about land given to Black Loyalists, we don’t mention that much of it was stolen from Indigenous Nations through colonialism and genocide. We don’t explain that the majority of the Black Loyalists who came to Canada were still enslaved and arrived as property of their white Loyalist owners. We don’t clarify that Black Loyalists were not given the same land as white Loyalists in terms of quality and size, with some Black Loyalists waiting years to receive less than 1 per cent of what white Loyalists received. We don’t acknowledge that many could not afford to live with the lack of land and jobs and therefore sold themselves to merchants for a term of service, effectively returning to enslavement because they had no other options. We don’t remember that due to the violence and racism they experienced in Canada, almost 1,200 Black Loyalists fled to Sierra Leone in 1792 to establish the colony of Freetown.

Similarly, in discussing the Underground Railroad, we don’t bring up the more than 200 years of Black and Indigenous enslavement in Canada. At the same time that escaped enslaved people and Black Loyalists (often still enslaved) were coming to Canada in the late 1700s, there were between 1,200 and 2,000 enslaved Black people in the Maritimes, around 300 in Lower Canada (now Quebec), and between 500 and 700 in Upper Canada (now Ontario). Further, of the 30,000 enslaved Black people who escaped to Canada through the Underground Railroad, around two-thirds returned to the United States after the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863.

And when Black people entering Canada at this time were given land, their allotments were primarily taken from remote (rural) and uncleared areas, especially in the Maritimes and southern Ontario, deemed undesirable to white people already living in Canada. It is ironic, then, that Black people should now be erased from the very rural spaces to which they were shunted off upon their arrival.

We don’t remember that due to the violence and racism they experienced in Canada, almost 1,200 Black Loyalists fled to Sierra Leone in 1792 to establish the colony of Freetown.

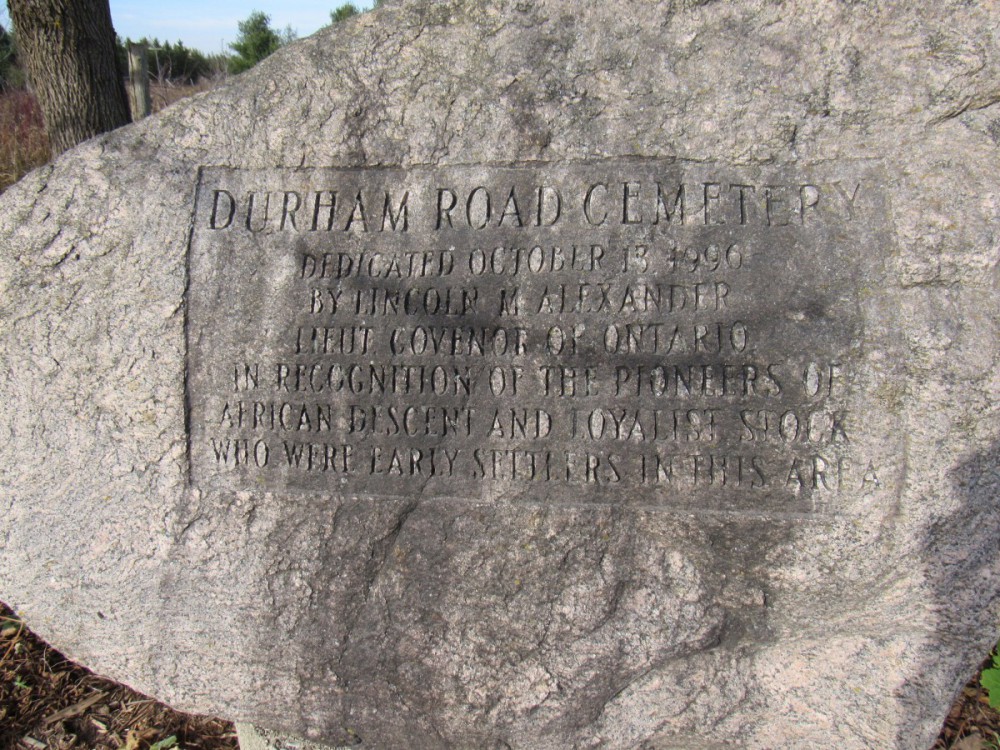

My own childhood education speaks to this erasure. The rural area where I grew up, Grey County, Ontario, was formerly part of one of Canada’s biggest Black settlements in the early to mid-1800s known as “Queen’s Bush” on Treaty 45 ½ territory. As a public-school student in the early to mid-2000s, we learned about white settlers in history classes, but none of us learned that Queen’s Bush had 13,000 Black settlers by 1852 or that just outside the town limits was a recently uncovered Black cemetery that had been farmed over for decades and thereby temporarily erased. Ultimately, many of the Black settlers in this area were forced to move to the nearby cities of Owen Sound, Collingwood, and Oro Station when the land they had cleared and planted became desirable to a new wave of European migrants, and governments prioritized these new white settlers over existing Black settlers. Today, the Black rural communities that were prominent in the 1800s have nearly all dissolved or been significantly reduced.

Modern migrant exploitation

Unfortunately, the Canadian state’s exploitation of Black people who come to rural Canada in pursuit of a better life is not a thing of the past. I spoke with Gabriel Allahdua, a former participant in the Seasonal Agricultural Worker Program, who explained to me the many ways in which Canada profits off of the extreme mistreatment of migrant workers. He came to Canada through the program after a hurricane in 2010 made finding work impossible in his home of St. Lucia. Allahdua worked on a Leamington, Ontario, farm and today, he’s an activist with Justicia for Migrant Workers. His story isn’t uncommon – many Black Caribbean migrants travel to rural Canada each year to work as labourers on local farms.

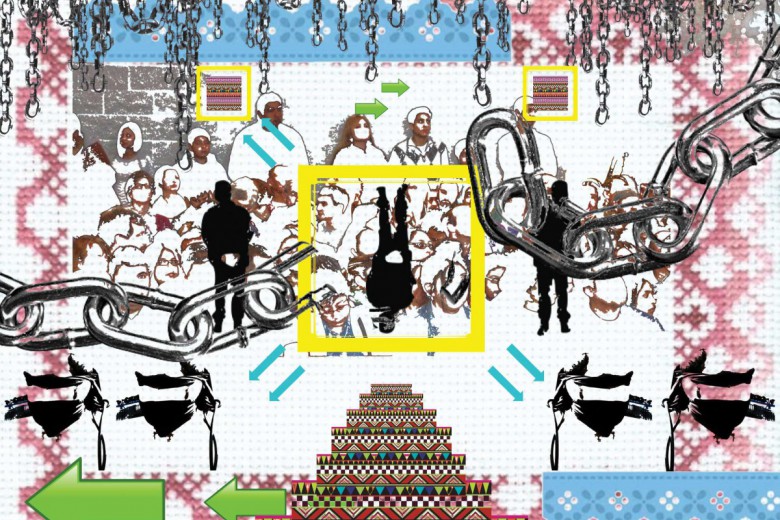

As Allahdua explains, “Canada creates its own workforce for migrant worker programs through its destabilizing activities that wreak havoc on the Global South. Canadian extraction, climate change contributions, and neocolonial trade policies force people off the land and make local business completely unsustainable.”

“Canada is asking countries to send low-educated, especially illiterate people or those with English as a second language, with the implication that these are Black people and people of colour who know very little about labour standards,” he continues. “They welcome migrant workers into a climate of fear. To keep us compliant, they keep us poor and ignorant. This is a formula for exploitation.”

“Canada creates its own workforce for migrant worker programs through its destabilizing activities that wreak havoc on the Global South."

Despite living within Canadian borders and paying provincial and federal taxes, migrant workers have limited access to health care, pensions, and employment insurance. Employer-provided housing is often overcrowded and unsanitary, and there are few consequences for employers who subject workers to unsafe environments. Many workers are paid below minimum wage.

When Canada accepts migrants with lower levels of English comprehension into the Seasonal Agricultural Worker Program, it echoes Michelle Alexander’s description of enslavement in the United States in her book The New Jim Crow: “Instead of importing English-speaking slaves from the West Indies, who were more likely to be familiar with European language and culture, many more enslaved people were shipped directly from Africa. These slaves would be far easier to control and far less likely to form alliances with poor whites.” Meanwhile, in Canada, “skilled” migrants who can prove English or French proficiency are put on a fast track to permanent residency.

Migrant worker programs contribute to the erasure of rural Black life. As Allahdua explains, “the whole program is designed to make migrants invisible, relying on exploited Black and POC labour while keeping them separate from the rest of the community in which they work.” As an example of this segregation, in the spring of 2020, a Grey County grocery store that sells food harvested by migrant farmers mainly from Jamaica asked the supplying farms not to let their workers shop there anymore because, due to COVID-19, their presence might make other customers feel uncomfortable. It wasn’t because any of the workers were sick, but because they were deemed “outsiders.”

Migrant workers are both essential to our food system and treated as disposable, denied access to the literal fruits of their own labour.

But the conditions that Black migrant workers face show that racism is more than interpersonal dislike or disregard – it’s structural denial. Indeed, migrant workers are legally removed from society – restricted in their mobility and tied to their employer under the conditions of their work permits. While racial segregation has been officially discontinued, citizenship-based segregation – which overwhelmingly falls along racial lines – has taken its place.

Migrant workers are both essential to our food system and treated as disposable, denied access to the literal fruits of their own labour. It’s reminiscent of how early Black settlers worked to clear and farm the land but then were barred from benefiting from their efforts when they were forced to leave their farms.

Collectively, Black people have made huge contributions to rural Canada over the last few centuries – creating wealth for enslavers, clearing land later appropriated by white farmers, and forming the backbone of our current local food system. Erasing Black rural history and modern-day presence serves the nationalist myth of Canadian racial tolerance. Undoing this erasure is the first step toward real racial justice.

Imagining just rural afrofutures

Organizing against anti-Black racism in rural areas is difficult when those places lack large Black communities. We urgently need to build connections between Black rural dwellers and develop networks that can spring into action when necessary.

In 2020, as Black Lives Matter protests and uprisings against police brutality rocked the globe, people in Grey County, as well as in other rural Canadian communities, joined the movement.

Pat Lorenzo was one of the speakers at a Black Lives Matter rally in Owen Sound that drew around 1,000 people from the city and surrounding rural areas. Reflecting on the event, Lorenzo tells me, “I was shocked to see so many white people. It was inspiring because we need white people to understand our struggles and to stand with us in fighting against oppression.” I tell her that I, by contrast, was shocked to see so many Black people. Lorenzo says she felt the same way the first time she attended the Owen Sound Emancipation Festival.

Owen Sound, Ontario, was the northern terminus of the Underground Railroad and has held the longest-running emancipation festival in Canada, celebrating the end of enslavement in the British Empire every year since 1862. The festival, which is held at the beginning of August to coincide with Emancipation Day, includes the “Emancipation Celebration Picnic” for descendants of Black people who came to the area through the Underground Railroad. Many locals, as well as Black people with connections to the area from places like Nova Scotia and the United States, gather to celebrate local Black history through educational talks, art exhibits, performances, and other events.

Lorenzo is the vice-chair of the Owen Sound Emancipation Festival and also volunteers to speak at local schools about Black history. Last year, she had trouble getting schools to let her speak to students, until a serious incident of racism happened in the area. Soon after, so many teachers asked her to speak that she couldn’t keep up with demand. “This tells me that there is a need,” she says. Her two Black children and one mixed-Black child, now in their 30s and 40s, had a difficult time with racism in nearly all-white schools in Grey County. It prompted her to spend time in her children’s schools engaging with white children who may not have had significant contact with Black people before. While classrooms are slightly more diverse now, she still sees Black education as important for all students.

“I tell them about the richness of Black people. It’s so rich, it’s so diverse, and it’s so amazing."

While institutionalized racism, rooted in enslavement, continues to shape modern experiences of anti-Black racism, Lorenzo emphasizes that Black people are so much more than the horrendous suffering they’ve been subjected to. When she goes to schools to talk to kids about Black history, “I tell them about the richness of Black people. It’s so rich, it’s so diverse, and it’s so amazing,” she says.

Organizations like the Ontario Black History Society are calling on the government to incorporate comprehensive Black education into the provincial curriculum. Celebrations of living history like the Owen Sound Emancipation Festival are drawing people in to learn about our past and rebuild broken networks of Black descendants and allies.

But justice for rural Black Canadians also means changing laws so the most marginalized Black people in rural Canada – migrant workers – are guaranteed safety and dignity. As Allahdua says, “Justice for migrant workers starts with granting them status. This would take care of the numerous labour and immigration problems. This will, of course, not end racism entirely, but it will address some major problems.” In fact, Black Lives Matter Canada lists status for migrant workers as one of its demands.

Black people who are carving out space in rural areas should connect their struggles against racism with Indigenous people who have been fighting white supremacy for centuries. We also need to strengthen solidarity with migrant workers, some of whom are our neighbours, as we fight in tandem for our right to be here and to protect the land we love.