On August 4, 2022 , a hearing was held over Zoom by Ontario’s Landlord and Tenant Board (LTB) to consider whether 64-year-old Sameerah Esho would be evicted. On that day, she was trying to participate in an online hearing, via telephone and in her third language, to keep her home of 10 years. After trying multiple times, she could not join the Zoom hearing. In fact, she had never used Zoom by herself before. The first time she used Zoom was months later during a session that was set up for her and an interpreter at her local legal clinic, for an interview for this article.

Esho shares a two-bedroom apartment with her son in Rexdale, a neighbourhood in northwest Toronto. They pay $1,334 per month. Her income from disability benefits, around $1,300 per month, does not fully cover her rent. When her landlord first served her with an eviction notice, she began searching for a new home. Most she found were over $2,000 per month – a sum far beyond her meagre budget, but one consistent with the current average rent for a one-bedroom in Toronto.

“I told [the landlord] everything is so expensive. I can’t afford anything else,” Esho explains. “Where would I go? My daughter is currently helping me with food because all of the income that I have goes toward the rent. I don’t have anything left. So I don’t know what I would do, because I don’t have enough money to move.”

60 per cent of renters said in a recent poll that they have had to cut back on food to afford their rent.

In late 2020, in the middle of an ongoing pandemic and a housing crisis, Ontario’s Landlord and Tenant Board (LTB) transitioned to a “digital-first” policy for all future eviction proceedings. Almost all matters before the LTB are now heard via Zoom – a change that has provoked widespread criticism from tenants and their advocacy groups, large swaths of the legal community, and even many landlords across the province. “The LTB likes to say they are digital first but not digital only,” explains tenant duty counsel lawyer Melissa Bramson, “but they’re basically digital only.”

Esho’s case is one of up to 80,000 applications that the LTB receives each year, with the vast majority of them being eviction applications filed by landlords. In theory, the digital-first policy was meant to address a backlog of cases, limit transmission of COVID-19, and align the provincial tribunal system with the broader government transition toward a new “digital Ontario.” But in practice, it’s created an opaque and inaccessible system that tips the scales of justice toward landlords.

Tenants’ challenges with the digital-first system extend from the realities of poverty and hardship: a lack of money to purchase and maintain technology, non-existent or slow internet connections, language barriers, disabilities, and unfamiliarity with digital systems. Other challenges are a result of how the new infrastructure has been designed – an unreliable patchwork of phone, email, and video conferencing technologies that often maroon participants in waiting rooms for hours on end and deny them the ability to meaningfully participate in their own legal proceedings. Talking with tenants and their advocates, we learned that these new digital infrastructures are creating a far more expedient eviction process.

The average rent for a one-bedroom in Toronto is $2,500 a month – a 23 per cent jump over the past year.

The two of us – Yodit and Michael – are Torontonians who have grown increasingly concerned about the housing crisis in our city. Yodit is the director of legal services at the Rexdale Community Legal Clinic, where she works to defend tenants against eviction. Over the past several years, she’s faced a growing realization that there are systemic issues making it almost impossible for low-income Ontarians to live in safe, dignified, and affordable housing. Sameerah Esho is just one such person who turned to the Rexdale clinic for help. Michael is a PhD student studying issues of eviction and digital infrastructure alongside other advocacy work related to food sovereignty, student housing, and electoral reform.

A housing and evictions crisis

At the time of writing, the average rent for a one-bedroom in Toronto is $2,500 a month – a 23 per cent jump over the past year. This means that each time tenants are evicted, it’s harder and harder for them to find a new place they can afford to live.

The reasons for this are complex and interconnected. Housing is treated as a financial commodity: investors buy up apartments with the goal of maximizing both the number of tenants and the rent per unit. Mom-and-pop landlords are being bought out, replaced by large corporate owners like real-estate investment trusts and private equity firms that buy and manage properties using a pool of money from many investors.

Since 1995, 65 per cent of rental unit purchases have been by financialized landlords.

Corporations and investors are allowed to act in this way because Ontario’s provincial and city governments have taken a laissez-faire and market-driven approach to regulation. They underfunded affordable housing and shelters, failed to intervene while ownership concentrated in the hands of corporations, and delayed promised increases to the minimum wage. While there are rent control rules that prevent an Ontario landlord from raising the rent on existing tenants, vacancy decontrol means there is no limit to how much they can jack up the rent when the old tenant moves out and a new one moves in. Such policies create a strong incentive for landlords to evict long-term tenants. Taken together with the fact that the minimum wage is far from a living wage in Ontario, it is no wonder that 60 per cent of renters said in a recent poll that they have had to cut back on food to afford their rent.

At Toronto Metropolitan University, assistant professor Nemoy Lewis is studying the impact of financialized housing on Black renters in Toronto. With the assistance of Dimitri Panou, he’s compiled 27 years of eviction data from across Ontario, and found that since 1995, 65 per cent of rental unit purchases have been by financialized landlords. “For the last four years, we’ve noticed that evictions are concentrated in three different parts of the city, one being the North Albion community, second being the Jane and Finch community, and the third being the Chalkfarm community, which is located just north of Jane and Wilson,” Lewis explains. These areas feature significant Black populations, and he says that one real-estate investment company called Starlight Investments has bought up much of the housing stock in these three areas since 2012.

Lewis’ work confirms what housing advocates and renters have long understood anecdotally: oppressed groups – Indigenous, Black, racialized, and poor people – face a rental market that does not meet them where they’re at. And if they find themselves homeless after being evicted, they are then met with an over-capacity shelter system and a municipal government that’s prepared to spend millions to violently evict people living in parks and other outdoor spaces.

Physical worlds become digital worlds

The LTB is one of 13 non-court government tribunals in Ontario. While Ontario’s other tribunals investigate complaints by civilians against police, decide on prisoners’ parole, and hear claims of discrimination, the LTB resolves disputes between landlords and tenants. In his book Unjust by Design, lawyer and former judicial chair Ron Ellis explains that tribunals operate as “surrogate courts […that] comprise a little-known system of administrative justice that annually makes hundreds of thousands of contentious, life-altering judicial decisions concerning the everyday rights of both individuals and businesses.”

In Ontario, an eviction can take place only after a very particular legal process has been completed – which starts with a landlord serving an eviction notice to a tenant based on a complaint (for example, owing rent). Next, the landlord must submit an eviction application to the LTB that triggers the scheduling of a hearing, during which an adjudicator considers evidence and arguments from both parties. Following the hearing, the LTB issues an order accepting or dismissing the claims raised in the landlord’s application and decides whether or not the tenant will be evicted as a result. If the LTB has granted the eviction application, a landlord can only enforce it by submitting it to the Court Enforcement Office. After that, a tenant will be given an approximate date at which point the locks to their home can be legally changed by a sheriff.

In 2020, the Ford government passed Bill 184, which allows tenants to be evicted without a hearing if that tenant is a dollar short or a day late on their arrears repayment plan.

Few decisions are more life-altering than eviction. And most people engage in these kinds of legal proceedings infrequently – sometimes just once in their lives. For a tenant to meaningfully participate – understanding the claims against them, refuting allegations, proposing viable solutions to remain in their home, or asking for compassionate relief from eviction – these hearings must be accessible, intelligible, and fair.

On March 19, 2020, as the pandemic swept through Canada and Canadians were told to stay home, Ontario moved to temporarily ban evictions. The ban was lifted in July 2020, and when LTB hearings for evictions resumed on August 1, they did so entirely via telephone or videoconference. A piece of pandemic-era legislation, the Hearings in Tribunal Proceedings (Temporary Measures) Act, 2020, empowered tribunals with even greater ability to conduct their hearings in any manner they deem appropriate. This legislation was part of the context and rationale that led to the announcement of a move to “digital first” by the LTB in September 2020.

Decisions for “alternative hearing formats” are now ambiguously made on a case-by-case basis. Tenants can now request an in-person hearing by filing an accommodation request, but the form is accessed online and is only in English and French. To date, we know of only two times when the LTB has allowed an in-person hearing since their “digital-first” policy was announced in 2020.

The LTB’s digital-first policy has denied tenants the right to meaningfully participate in their hearings, and thus may be violating Ontario’s Human Rights Code.

The LTB’s website offers a range of other accommodations – including a program to loan out cell phones, and five public-access terminals across Ontario equipped with a phone and computer – that are mostly accessed through the same accommodation request form. But these band-aid solutions are a poor replacement for the robust, in-person supports that the LTB once offered. “I don’t think the [LTB] fully appreciates the seriousness of the digital barrier,” Bramson says. “There is nothing that can beat a human interaction.”

Prior to the “digital-first” transition, the LTB operated eight offices and hearing rooms across the province: in London, Ottawa, Mississauga, Hamilton, Sudbury, and three locations in Toronto. These sites contained the physical rooms where tenants, landlords, and their legal representatives would gather in person for hearings. They also allowed parties to speak directly with LTB representatives, print and submit documents, and for tenants to meet with duty counsel in person.

On the day of their hearing, a tenant would arrive at one of these physical locations – for example, on the seventh floor of 47 Sheppard Avenue East in Toronto – and check in with a commissionaire. In a hearing room, the adjudicator would begin an official electronic recording for the day, make important announcements, and then call on parties to hear their applications. Tenant duty counsel representatives – lawyers, paralegals, and legal workers who are tasked with helping unrepresented tenants who are facing eviction – would often be invited to announce their services during the introductions. Meanwhile, the commissionaire would typically hand the adjudicator a list of those in attendance, so that even if a tenant was outside the room, it was clear they were ready to participate. During the morning, afternoon, or full-day hearing block, tenants and landlords (often via their legal representatives) could work out a settlement.

When a tenant tries to participate, but is stymied by technology, instead of rescheduling the hearing, the LTB often proceeds regardless and orders an eviction without the tenant being allowed to share their side of the story.

As Bramson recalls, “so much work was done in the hallways. […] We would come up with really fantastic resolutions in those hallways.” Parties could also put their names down on a waiting list for in-person mediation. Trained mediators would then help tenants and landlords settle their issues so that a contentious and lengthy hearing could be avoided and, in many cases, a tenancy saved.

In those buildings, legal advice was kept confidential and tenants had access to various supports. Tenant duty counsel had private spaces in which to meet with tenants, connect over the phone with language interpreters; provide on-the-spot referrals to legal clinics or financial support, and even represent the tenant in all or part of their hearing that day. Sometimes, a tenant just needed a free printer to print their evidence. If the tenant didn’t have their eviction papers, tenant duty counsel could walk up to the front desk and ask for the documents. Claire Littleton, a legal clinic lawyer in Thunder Bay, was once reported by a fellow lawyer to have provided advice, supervised a law student, and represented a tenant all while holding and soothing her client’s baby.

These offices have all been closed since March 16, 2020. There’s been no indication that they will be reopened, despite the fact that the province abandoned most COVID-19 regulations in early 2022. Other tribunals have taken a different approach as COVID-19 restrictions were lifted: for example, the Workplace Safety and Insurance Appeals Tribunal is now offering a hybrid hearing format and the Ontario Labour Relations Board is going back to in-person.

One tenant called in to her eviction hearing and spoke to someone she thought was an LTB mediator – only after she agreed to a repayment plan did she learn that she’d actually been negotiating with her landlord’s lawyer.

In remote communities, the LTB held mobile in-person hearings and set up a makeshift hearing room in a hotel or legion. This practice was eliminated during the transition to digital first in 2020 and replaced with Zoom hearings, despite the fact that many people living in remote communities have limited access to the internet or computers.

The mechanics of online eviction hearings

The new LTB model requires participants to be present – either online or by telephone – for a morning, afternoon, or throughout the entire day (9 a.m. to 4 p.m. or later) of the legal proceeding until their hearing is called by the adjudicator. For 9 a.m. hearing blocks, parties are told they must be ready to stay the whole day. The LTB does not provide individual hearing times nor do they account for technical failures or tenants dropping off calls – Bramson says a tenant can miss their hearing for something as simple as needing to step away to use the bathroom.

The official LTB decisions, made available online, are a catalogue of various technological issues: tenants disappear into Zoom breakout rooms, lose connectivity for unknown reasons, or have technical issues joining their hearings in the first place. When this happens – a tenant tries to participate, but is stymied by technology – instead of rescheduling the hearing, the LTB often proceeds regardless and orders an eviction without the tenant being allowed to share their side of the story.

“In Ontario, a majority of low-income tenants don’t have sufficient bandwidth to fully participate in their hearings.”

According to a 2021 study by the Advocacy Centre for Tenants Ontario (ACTO), 87 per cent of landlords were present at their LTB hearings, versus only 45 per cent of tenants. Landlords were far more likely to join via video and tenants far more likely to join by phone. “In Ontario, a majority of low-income tenants don’t have sufficient bandwidth to fully participate in their hearings,” explains Douglas Kwan, ACTO’s director of advocacy and legal services. “They need high-speed internet and a data plan that will allow them to fully participate in a Zoom hearing that could be four hours to six hours long. You also have to have the devices that help you participate, which includes a camera, printer or scanner that can assist in providing evidence. Participating by phone is a poor substitute.’’

Phoning in puts tenants at a distinct disadvantage. They are often seen as less credible, and images of them or their surroundings that might give context or generate empathy (for example, physical disabilities or a child in a stroller) are not shown. If photo or video evidence is shared, they cannot see or dispute it. “They don’t see the visual cues,” Bramson explains. “[Adjudicators] can’t see their reactions, their emotions. [Adjudicators] get really frustrated with tenants on the phone, saying ‘Stop talking, don’t interrupt.’’’ Multiple studies about a range of legal proceedings show that online hearings reduce the perceived severity of a legal proceeding for defendants and lead to less favourable outcomes for them.

According to a 2021 study, 87 per cent of landlords were present at their LTB hearings, versus only 45 per cent of tenants. Landlords were far more likely to join via video and tenants far more likely to join by phone.

People calling in to a Zoom hearing have to know a series of phone commands to navigate the meeting: to leave a breakout room they must press #; to mute and unmute they must press *6. As Kwan describes, “when a person is placed on mute [by an adjudicator], you cannot unmute yourself to object to evidence that may be of relevance: salacious, misheard statements or even outright lies. That’s placed on the record; the adjudicator hears it and that can’t be unheard.’’

Tenants and advocates who aren’t lawyers report feeling disoriented, confused, and lacking confidence in the fairness of the proceedings. Hearings are scheduled by the type of application as opposed to the region, meaning adjudicators cannot appreciate local circumstances and tenant duty counsel may not be able to refer tenants to nearby resources. It also means that if a landlord has submitted an application to evict a tenant, and the tenant has submitted a separate complaint against the landlord, their two applications get heard separately. This can mean an eviction is ordered before a tenant's concerns are addressed.

The earliest online hearings contained no avenues for private consultation between legal counsel and client – a serious shortcoming that is now partially addressed through Zoom’s breakout rooms. One tenant told the Globe and Mail that she called in to her eviction hearing and spoke to someone she thought was an LTB mediator – only after she agreed to a repayment plan did she learn that she’d actually been negotiating with her landlord’s lawyer. Mediators are also only assigned to certain hearing blocks so opportunities for resolving issues are reduced.

Adjudicators allowed children to act as translators in negotiations between landlords and their parents, and ordered a deceased tenant to pay rent arrears to their landlord.

Contrary to the LTB’s promise of increased access and efficiency, Kwan points out that even though there are more adjudicators and fewer applications being heard, the LTB’s backlog has meant that new and adjourned matters are currently being scheduled after seven to eight months, as opposed to the standard timing of about eight weeks.

Zoom was not designed for complex legal hearings, and it’s an oddly generic choice given the importance and specificity of these hearings. Even the most casual user of Zoom has had challenges – getting stuck in a waiting room, the cacophony of multiple people speaking at the same time, indecipherable speech, or lagging video. Zoom meetings are not end-to-end encrypted by default, and video users must opt in to ensure their data is protected. For those who are calling in by phone, there’s no chance to opt in. Zoom collects everything from users’ IP addresses to their job title, and shares that data with third parties for those companies’ “business purposes.”

Zoom is not the only troublesome technology – the LTB has launched an inaccessible, glitchy, and unreliable digital portal for submitting evidence and communicating with the other side. “[The] challenge has been navigating [the LTB’s] online world,” says Bramson, “so not only the Zoom hearings […] but it’s surrounding the Zoom hearings: their portal, their email systems, especially for clients or individuals with language or literacy challenges or individuals with serious mental health concerns.”

In April 2019, the Minister of Finance slashed the Legal Aid Ontario budget by 30 per cent, which in turn cut the budgets of legal aid clinics. Clinics that focus their work on improving renters’ laws saw the highest cuts.

Take, for example, a request to review an order: this is an application that, typically, a tenant must urgently file with the LTB to try and avoid imminent eviction. It can be filed via email, but only once the tenant pays a fee through an online payment portal. This ignores tenants living on low incomes who may not have a debit or credit card. The labyrinthine process described on the LTB’s website also contains little publicly facing information about the right of low-income parties to file a fee waiver request.

Tenants who ultimately lose their case, or whose requests for accommodation are denied, can try to engage in the LTB’s review process or appeal the decision to a Divisional Court, but these options are onerous and prohibitive for the same reasons tenants may have faced barriers in accessing the initial eviction hearing. Missing an eviction hearing is not like missing a work meeting where everyone is engaging voluntarily and with similar goals. As Kwan explains, this is a highly contentious and litigious environment where one party is fighting to keep their home, and the other is intent on taking it from them. ACTO asserts that the LTB’s digital-first policy has denied tenants the right to meaningfully participate in their hearings, and thus violated tenant rights under Ontario’s Human Rights Code. ACTO is representing multiple tenants in their human rights applications before the Human Rights Tribunal of Ontario against the LTB and Tribunals Ontario.

“Digital first” as a digital-legal infrastructure

The transition to online eviction hearings can be understood as new digital-legal infrastructure. Infrastructures are networks tasked with moving people, goods, and information across time and space. Importantly, infrastructure can illuminate long-standing accumulations of power – who is moved and who does the moving are largely based on who has amassed wealth and control. For example, governments can set up checkpoints to restrict access to roads; or telecommunication companies can collude to charge exorbitant fees for internet and phone service. Digital-legal infrastructure can be wielded the same way: it informs both the process and structure of an eviction hearing as well as access to one of the most important sites of life, the home.

Decades prior to the rise of these new digital worlds, philosopher Langdon Winner called for careful consideration around new technology: “Shielded by the conviction that technology is neutral and tool-like, a whole new order is built – piecemeal, step by step, with the parts and pieces linked together in novel ways – without the slightest public awareness or opportunity to dispute the character of the changes underway.”

Tenants’ challenges with the digital-first system extend from the realities of poverty and hardship: a lack of money to purchase and maintain technology, non-existent or slow internet connections, language barriers, disabilities, and unfamiliarity with digital systems.

When a government or company transitions between infrastructures, there’s often a period of overlap between the old and new infrastructure while people learn to use the new. The LTB has instead decommissioned the entire old network of in-person hearing rooms and offices, including service desks and even fax lines. “Digital first” was implemented with minimal consultation of legal clinics or direct input from tenants most severely impacted. While there have been multiple stakeholder meetings, Bramson noted that the LTB has not engaged in meaningful community consultation. And as LTB staff and adjudicators become more familiar with their platforms, engaging with them every day, tenants who may participate only once in their lives are seriously disadvantaged.

LTB & the Ford government’s agenda

The construction of the LTB’s digital-legal infrastructure did not happen in isolation; it was implemented alongside a series of changes by Doug Ford’s provincial government that mean eviction is now particularly devastating.

In April 2019, the Minister of Finance slashed the Legal Aid Ontario budget by 30 per cent, which in turn cut the budgets of legal aid clinics. Clinics that focus their work on improving renters’ laws saw the highest cuts. These legal clinics have won low- and middle-income tenants important protections in Ontario: they’ve halted evictions, advocated for broader rent control, helped introduce a standard lease form, and started a program to help low-income renters pay their power bills. “We are disturbed that our successes have made us a target for short-sighted and ill-informed cuts,” said ACTO in a press release after they lost a quarter of their provincial funding.

In 2020, the Ford government passed Bill 184, which allows tenants to be evicted from their homes without a hearing if that tenant is a dollar short or a day late on their arrears repayment plan. The government also exempted units built after November 2018 from rent controls – which means that some tenants in new builds have seen their rent jump by 25 per cent from one year to the next.

Ford has appointed new adjudicators with high-level connections to the provincial Conservatives, the RCMP, and landlord-side law firms.

Meanwhile, LTB staff jobs are becoming more precarious: many experienced senior staff were not offered contract renewals and new hires were offered limited terms and part-time work. Ford has appointed new adjudicators with high-level connections to the provincial Conservatives, the RCMP, and landlord-side law firms. Practice advisory committees, which once allowed tenant and landlord representatives to share feedback on the LTB’s rules and practices directly with LTB staff, have been quietly discontinued.

In the early days of Zoom hearings, members of activist groups like People’s Defence TO attended LTB hearings, recorded them, and shared the recordings online. They documented adjudicators allowing children to act as translators in negotiations between landlords and their parents, along with one case where a deceased tenant was ordered to pay arrears by an adjudicator. Despite assurances that the tribunal system is meant to be independent of political interference, the Ford government introduced legislation that criminalized the recording of hearings, with fines upwards of $25,000.

Finally, the 2021 budget saw cumulative reductions of $452 million for Ontario Works and the Ontario Disability Support Program (ODSP). A single person now receives $733/month in social assistance or $1,228/month in disability assistance – a sum that is supposed to cover rent and other necessities. In every way, poor tenants are being ushered out the door.

If they find themselves homeless after being evicted, they are then met with an over-capacity shelter system and a municipal government that’s prepared to spend millions to violently evict people living in parks and other outdoor spaces.

Sameerah Esho’s eviction hearing went ahead without her on August 4, 2022 – she was never able to join the Zoom meeting. The LTB heard nothing about how devastating eviction would be for her, trying to make ends meet on her fixed ODSP income. The adjudicator thankfully decided not to grant an eviction order. Esho is one of the lucky few tenants who missed her hearing but got to stay in her home. But tenants like her cannot continue to rely on luck amid a housing crisis and a dramatic, unprecedented shift in the ways eviction hearings are conducted. The stakes are too high.

Fighting for tenant rights

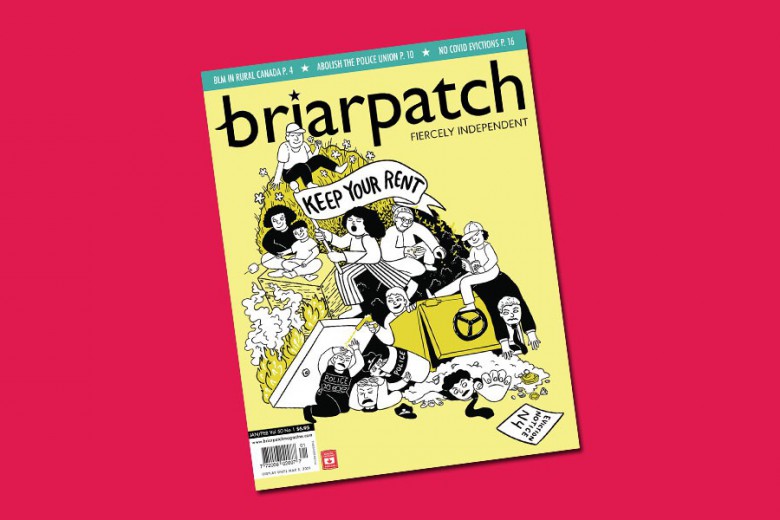

Despite the clear issues with the digital-first model, there are reasons for optimism. Tenant advocates have long struggled with the absence of reliable data around evictions in Ontario, but researchers like Nemoy Lewis and activist groups like Keep Your Rent have begun to track evictions and corporate ownership of rental housing, with the goal of empowering tenants and unearthing the roots of the crisis. “Eviction [is] a violent practice,” explains Lewis, but “it is rarely ever recognized as a violent practice – largely because it lacks either [an] appropriate or identifiable perpetrator, or lacks a cause-and-effect relationship where we don’t know who owns what in the city or who owns what building. So we don’t know in terms of who to direct our attention to.”

Esho’s case is one of up to 80,000 applications the LTB receives each year, the vast majority of which are eviction applications filed by landlords.

While academics and activists map Toronto’s housing crisis, community legal clinics and tenant advocacy organizations like ACTO keep sounding the alarm on the issues with online eviction hearings. ACTO has released numerous reports on this new digital infrastructure on their website and they’re envisioning potential solutions: Kwan says data supports a hybrid approach, adding, “we want parties to be able to easily identify the type of hearing format that they would prefer.”

If we understand that technology is not necessarily “neutral and tool-like” – that the people with the power to build digital infrastructure also have an interest in using it to impoverish marginalized communities and enrich corporations – then we can begin to form strategies of resistance and imagine how technology might help us achieve a future of stable, affordable housing for all Ontarians.