Sundus Abdul Hadi was born to Iraqi parents in the United Arab Emirates and raised in Montreal, Canada. As a multimedia artist, Abdul Hadi works mostly with painting, collage, sound, and digital art. Her work has been exhibited and featured in the U.A.E., Palestine, Australia, Iraq, and throughout the U.S. and Canada.

How would you describe your art?

It is both a reflection of our current times as well as a projection of an imagined reality.

Is there one source of energy or inspiration that drives your creativity more than others?

Inspiration is a hard word to use when it comes to my work because much of the subject matter I’ve worked with isn’t inspiring. However, the realities of war, occupation, and exploitation do hold stories of survival and resilience. I strive to record those stories visually. I’m also interested in ancient heritage and iconography and the age-old desire to create images that tell the story of our present.

How does Iraq fit into your consciousness and subsequently into your work?

That question relates to both a very personal sense of identity as well as a social sense of responsibility. The injustices suffered by Iraq make it a powerful symbol of the state of our (my) world, politically and metaphorically. Every Iraqi, no matter how apolitical, has suffered from corruption and violence first-hand. But through suffering there is also healing. That is where I’m at now. It is necessary to acknowledge the tragedies, but one must also focus on how to overcome them.

You grew up in the United Arab Emirates and lived most of your life in Montreal. How do the concepts of home, exile, belonging, and distance figure into your art?

My art has always dealt with these concepts, at least between the lines. After all, I wasn’t born or raised in Iraq and only have citizenship rights in Canada.

It’s a complex equation. On my visits to Baghdad, I was always considered an “ajnabiya” (a foreigner), whereas in Canada, my identity as an Iraqi was always forefront. I spent much of my adult life exploring these complexities until my identity crisis played itself out. As confusing or contradictory as my identity may be, I now accept myself openly and without prejudices.

Do you make art so it can be a vehicle for encouraging social change?

I hope to create an image that incites questioning and reflection. I also hope to encourage viewers to produce their own work and tell their own stories, no matter the medium. The ultimate privilege is when someone is inspired enough by your work to create their own music, art, or writing.

What expectations and limitations face contemporary artists from Iraq and the wider Arab world?

That’s a multifold question because expectations and limitations can be self-imposed, imposed by government and surroundings, and imposed by the art industry. Artists living in Iraq face different challenges than we do in the diaspora.

I have the utmost respect for artists who produce in dire situations and with limited resources, sometimes even lacking electricity. That said, one of the underlying limitations within Iraq is that being an artist isn’t considered a respectable profession.

And there are just as many expectations and limitations in the established art industry globally. I have certainly encountered censorship and industry politics. The art world is as corrupt and incestuous as any big-money institution. Opportunities are monopolized by big-name galleries and associations. It’s about who you know (wasta!).

Being an independent artist makes it more difficult to exhibit, sell, expose your work to wider audiences, or gain the respect of larger institutions. But you should never underestimate the support you can get from small, community-oriented organizations to take on projects or exhibits that larger institutions shy from.

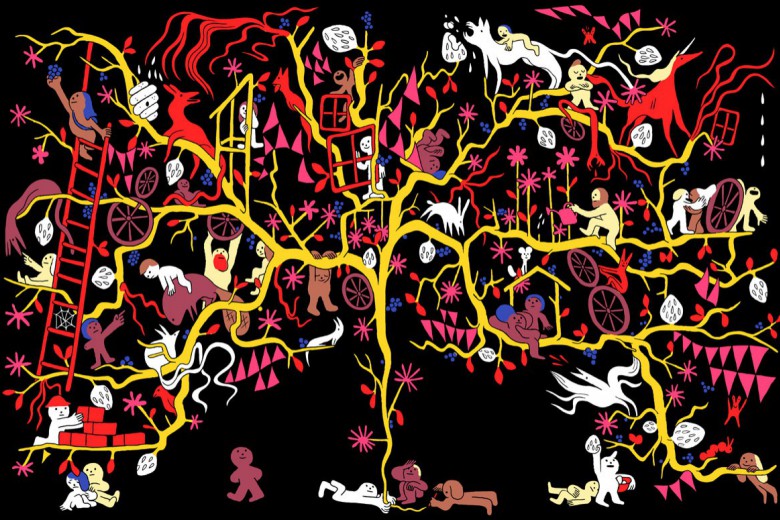

Your major body of work thus far has been Warchestra. Can you describe its inception, its early childhood, and its reception?

Warchestra was born as my response to the representation of the Iraq War in Western media. As a spectator as well as someone intricately connected to its tragedy, I felt a responsibility to counter the stereotyping and one-dimensional imaging that was prevalent.

My interest and research in the rich cultural heritage of Iraq, coupled with the musical environment I was surrounded by in Montreal, were foundational. I aimed to subvert media propaganda by replacing weapons of violence with objects of culture, creating counter-imagery. Warchestra’s goal was to redefine, reimagine, and reinvent the war in Iraq through art. It became a collaborative effort with hip-hop artist The Narcicyst and a handful of other inspiring musicians and poets. We created a soundtrack to each painting, transporting the viewer/listener to a reimagined space of image and sound.

As an artist and an Iraqi in the diaspora, it was really intense. I spent so much creative energy meditating on the destructive nature of violence, politics, and war. In the process of transforming the concept from war to one of empowerment, I became creatively and mentally drained.

In Flight, your second major body of work, you add the realms of photography and type. Why the change? What were you able to communicate through this form as opposed to paint and collage?

After Warchestra I needed to unlearn my artistic process, which had become unhealthy. I wanted to feel inspired again, after years of focusing on war. So I quit my job, closed my studio, and decided to travel for six months, beginning with an artist residency in Palestine with Al-Mahatta Gallery before a journey that led me to nine countries.

So my work had to become mobile. I went back to my roots as a graphic artist in order to create with limited resources, collaborating with my sister Tamara whose photographs have always been a source of inspiration. Although I find graphic art to be less challenging than the physical act of painting, digital collage can be just as rewarding. It was the perfect medium for me during the transitional period of healing, travel, and new collaborations.

In Flight, you visited many places outside Iraq, the exclusive locale of your previous work. What are the connections in your mind between Iraq and Syria, Lebanon, and Egypt?

I was actually very hurt about Iraq throughout the production of the Flight series. I felt let down by my country. My last visit to Baghdad was very difficult. I experienced one of the most intense bombings of 2009 on December 8. After that day, I felt disdain toward Iraq – the fear, violence, tragedy, and trauma so abundant there manifested within me.

What hurt the most was that I felt that my people had given up, normalized the abnormal and hardened to its realities. I felt I didn’t belong there. I felt rejected and judged by my people. This caused a deep conflict for me, both in terms of identity and artistic process, since my art was centred on Iraq for many years. The Flight series helped heal that internal conflict, and I spread my reach toward other countries and places touched by daily injustices similar to those in Iraq.

Suffering is indiscriminate, and healing should be as well. It wasn’t about making political references anymore, but rather about the human condition of rising above hardship, especially in light of the events of the so-called Arab Spring.

The Arab Winter was a Montreal-based collaborative project responding to the Arab Spring. Why did you call it the Arab Winter, and why Montreal?

When the opportunity to curate a show in Montreal came up in 2011, The Narcicyst, eL Seed, Tunisian calligrapher Karim Jabbari, and I started brainstorming for a concept that referenced all of our work and identities. We all had a foot in Montreal and a foot in our homelands, and we were all directly touched by political events before and after the Arab Spring.

More than anything else, we were all critical thinkers with a degree of hesitation regarding the celebratory representation of the Arab Spring. As exciting as it was, we didn’t buy into the hype. Hence the title, coupled with a tongue-in-cheek nod to the brutal Montreal winter.

Is there an ideal audience for all your works? Do you want a particular group of people, age, mindset, or background to be exposed to your work? Does the audience factor into your work at all?

Audience is possibly the most important factor I consider when I create. The duality of my identity as a blend of both East and West sensitizes me to both societies and communities. I am fully aware of that responsibility because even visual language can be misinterpreted. For example, this spring, my work will be included in a group exhibition of female Iraqi artists at the National Veterans Art Museum in Chicago.

I was very apprehensive at first and had to carefully consider the circumstances, statements, and context around the exhibit before I agreed. Luckily, I trust the curator and know that she is very cautious about how easily the exhibit can be used to normalize the complex, loaded, and imbalanced relationship between the U.S. military and Iraq. The fact is, if our voice as Iraqi women is not included in the context of the veterans museum, it perpetuates the omission of the Iraqi voice in discourse about the war and occupation of Iraq. And we are neither quiet nor soft-spoken with our art.

I want people who’ve only encountered Iraqis through war and occupation exposed to my work. Simultaneously, I also want Arabs who never consider sharing their stories through art exposed to my work. To teach and to share. To change perspectives.

This interview is adapted and abridged from Ahmed Habib’s extended interview at shakomakoNET.