Of the dozens of generally crappy jobs I’ve held since my teens, only two have been at union shops. That’s two more union jobs than most people under 35 have had. According to a 2012 poll, just 15 per cent of Canadians strongly agree that gains unions make for their members also improve the lives of non-members. Amid this broader erosion of union legitimacy, it also remains an open question how much inspiration – let alone insurrectionary fervour – members experience inside unions.

Many on the left root the decline of organized labour in the 1980s under Mulroney, Reagan, and Thatcher. It’s a story of the rise of free market ideology and the power of Wall Street. According to this story, moneyed interests with the wrong ideas took hold of the levers of policy, and that’s why today university graduates make 10 bucks an hour bagging arugula and kumquats at Whole Foods.

The story has genuine villains, but we should be cautious not to let leaders stand in for a deeper understanding of the transition from the Keynesian welfare state to neoliberal globalization. In reality, it was the economic crises of the 1970s that ended the relative peace between big labour, big government, and big capital that had defined what’s called the postwar compromise.

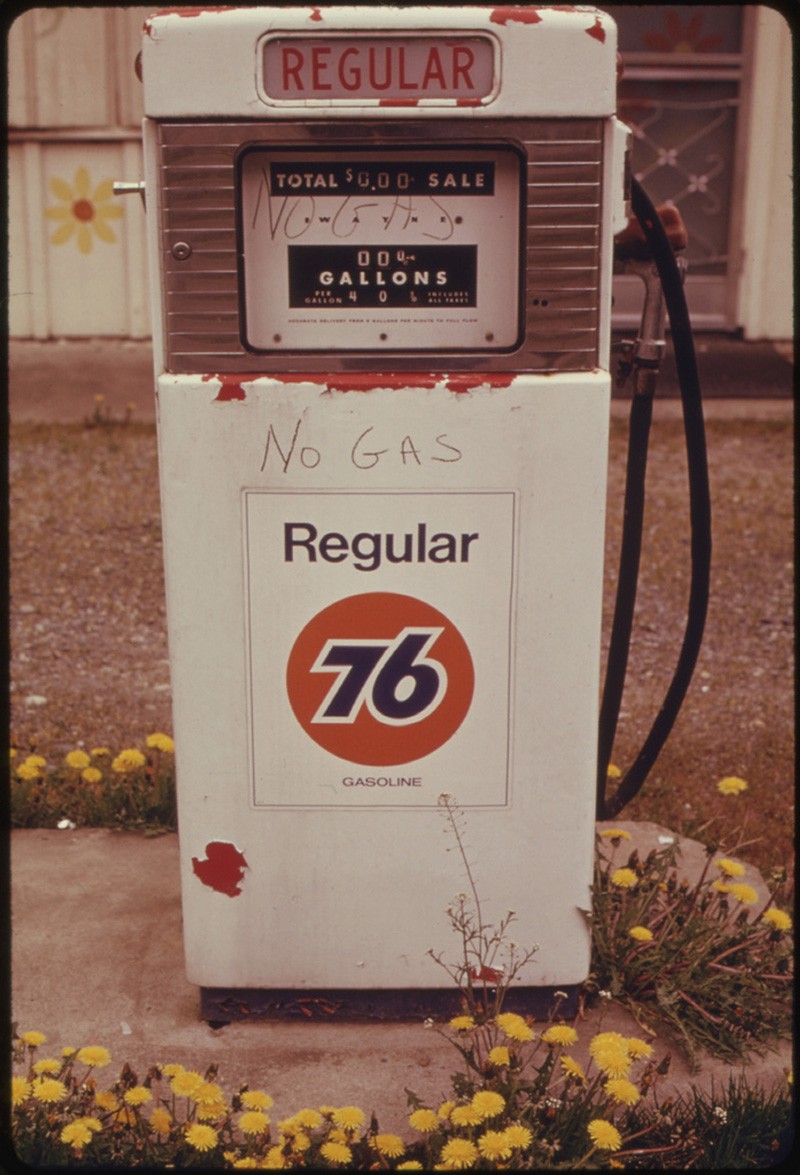

As the postwar “golden age” went bust in the early ’70s, the combination of runaway inflation, low economic growth, and public debt smashed the social-democratic consensus through which trade unions and social democrats had wed their fortunes to unlimited industrial expansion. Significantly, in tying labour’s fortunes to capitalist growth, the Keynesian compact embraced the full host of capital’s dictates, including Indigenous dispossession and oppression, environmental pillage, and suppression of liberation movements from Palestine to Guatemala.

It wasn’t Brian Mulroney but Pierre Trudeau who clamped down on organized labour with wage controls in 1975, and south of the border it was the Democrat Jimmy Carter who responded to the conundrum of high inflation and low growth by bringing on a dire recession via the “Volcker shock.” President Carter and his Federal Reserve chairman Paul Volcker jacked up federal interest rates to 20 per cent and the unemployment rate to above 10 per cent, ensuring the cost of capitalist crisis was borne by the working class. This was the same year, 1981, that Allan Blakeney’s NDP government in Saskatchewan instituted back-to-work legislation against a public-sector strike.

The hard lesson, here, is that the postwar compromise was dependent on supercharged capitalist expansion. Emboldened by low unemployment and hard-won gains, the power of labour in the ’50s and ’60s contributed to capitalist crisis by squeezing profits with improved conditions, wages, and benefits. At the same time, increased international competition and technological innovation led to a dramatic reduction in the manufacturing base and the precipitous decline of private-sector union strength.

Looking back, in Social Democracy After the Cold War, Ingo Schmidt notes the price of institutional legitimacy for unions was “unlearn[ing] how to mobilize and fight for their interests on the streets and picket lines.”

The ruling class, meanwhile, has learned that full employment greatly empowers labour, and so a policy of full employment – once commonplace across the West – is simply off the table. In the logic of the system, a massive population of surplus humanity, what Marx called the reserve army of labour, is essential. So long as social peace can be maintained, high unemployment forces competition among workers, keeps wages low, and even fuels public bitterness toward unions – a win-win scenario for capital and the state, especially when systemic racism and sexism are leveraged to deepen exploitation of workers.

From social democracy’s embrace of capitalism to communism’s male-centric glorification of industrial labour, there is enough failure on the historical left to go around for everyone. Perhaps it’s time to own it and, with patience and reflection, to build fighting organizations that match the reality of 2013, not 1965. This means finding ways to forge our struggles broadly and from below – in communities, schools, homeplaces, and city streets – not only on the job site. It means that some who’ve traditionally had the loudest voices in the labour movement must prepare to be led by newer voices rising on the margins.

_780_520_s_c1_c_t.png)