Disability justice offers a refuge and a compass for our collective work as organizers amid the ongoing, overlapping crises of our time. To embody disability justice is to make ourselves antagonistic to capital. To move toward freedom interdependently, sustainably, and across abilities. To stay open to new forms of resistance we have not yet imagined. To leave no one behind. Disability justice is neither a destination nor a solution, but a practice of disorderliness, an experiment in motion.

Disability justice and its antecedent, the Mad Pride movement, reveal how structural violence comes to live in the body. How colonial psychiatry and medicine pathologize our resistance, as enemies of capital and empire, to the conditions of society that make us unwell. A disability justice politic insists on life and its inherent value outside of commodity relations and capitalist notions of productivity. It asks: what is more precious than life? And how do we steal life back from capitalism – within, outside of, and against the institutions in which we are embedded?

In a world forged through disability justice organizing, living together is not a sound, single and coherent, but a noise – unruly and wild, and therefore ungovernable. The essays, books, videos, and articles we, Noa and Jody, have gathered here embrace this wildness – looking to the past, present, and future of Mad, sick, and disabled life for roadmaps toward revolution, in all its possibilities and contradictions.

“GET WELL SOON” (2020)

"Get Well Soon" is part of the project getwellsoon.labr.io by Sam Lavigne and Tega Brain.

Written during the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, this short lyric essay by Johanna Hedva articulates the revolutionary potential of sickness and communal care. In it, Hedva argues that illness and revolution, often seen as opposites, are actually defined by a shared temporality and set of demands. “As many chronically ill and disabled folks know, the now of illness soon radicalizes, reveals its subversive power, and produces a politic,” Hedva writes.

Hedva’s radical politic calls on us, as organizers, to expand our vision of what revolution might look like: “Perhaps it doesn’t look like a march of angry, abled bodies in the streets. Perhaps it looks something more like the world standing still because all the bodies in it are exhausted – because care has to be prioritized before it’s too late.”

“Disability justice movements: history and practice” (2022)

In this article, drawn from a roundtable held at the Socialism 2022 conference, Dana Cloud and Nina Lozano argue that disability justice must be at the forefront of any militant socialist or anti-capitalist project. Cloud begins with a succinct history of direct action and protest for disability justice in the so-called United States, which culminated in the U.S. government passing the Americans with Disabilities Act in 1990. Central to the strength of this struggle, she says, was cross-movement solidarity between disability rights groups and other groups such as the Black Panthers, United Farm Workers, queer liberation organizations, and many more.

Lozano expands on this analysis, writing on the role of mutual aid and community care as strategies to decouple capitalism’s exploitative economic structure and the ill/disabled body as a site of profit extraction. They invoke Mad education-scholar Shayda Kafai’s concept of “crip-centric liberated zones,” where queer, brown, and Black disabled people reclaim our care from the state – cooking meals, sharing meds, organizing accessible meetings and protests – as a strategy to build

crip power.

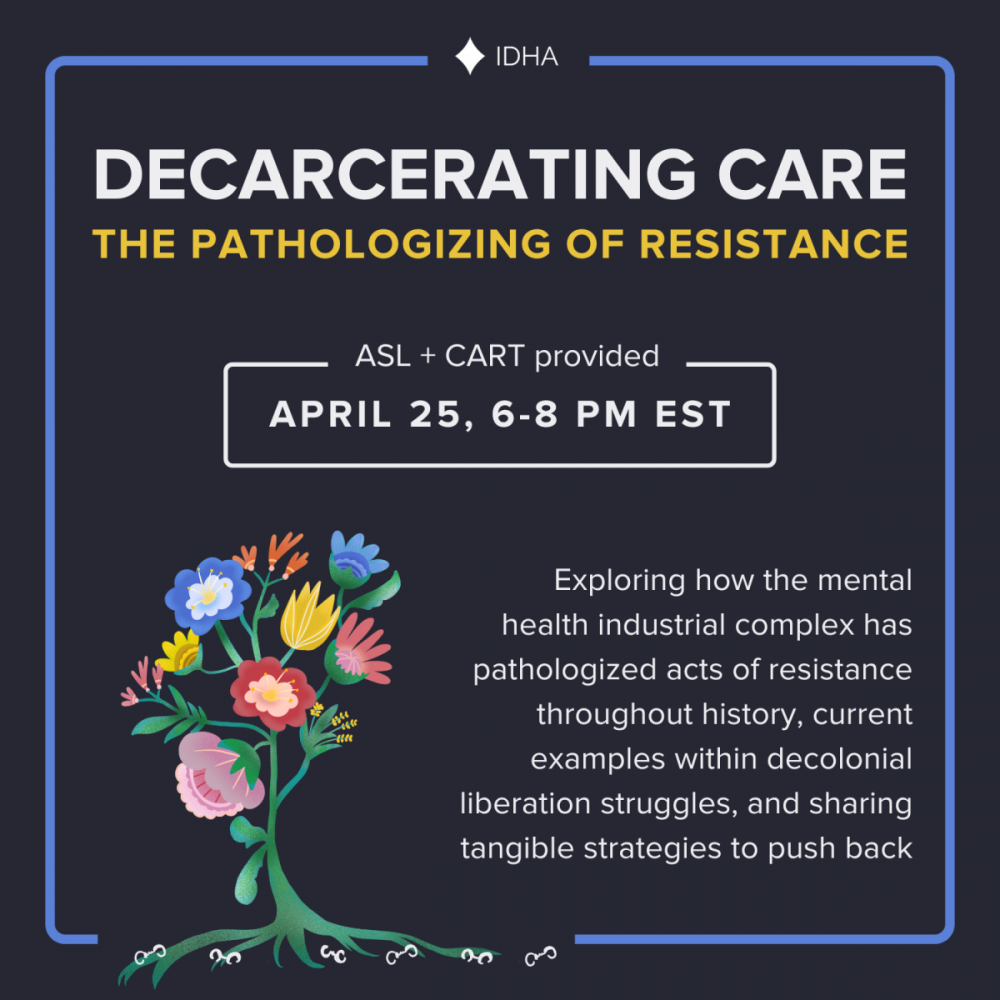

“Decarcerating Care: The Pathologizing of Resistance” (2024)

In this panel conversation for the Institute for the Development of Human Arts, Idil Abdillahi, Gina Ali, Samah Jabr, Hannah Throssell, and Sasha Warren discuss how the state weaponizes the languages of madness and diagnosis to suppress and pathologize acts of resistance. When we resist, Dr. Abdillahi says, we are deemed “disruptive, disturbing, dangerous, and outside of the norm.” Hunger strikes, self-immolation, armed resistance – the mainstream media rebrands these intentional acts of protest as a symptom of the suicidal and the mentally ill.

Like Hedva’s lyric essay, this conversation considers madness as an unwillingness to adopt empire’s agenda. As Dr. Abdillahi goes on to ask, “What does it mean for us to enact madness, to animate madness, to animate refusals, to animate life, to animate choosing our comrades?” Since the 20th century, Warren explains, psychiatry has fragmented and diffused itself over and over again, in an attempt to insinuate itself ever more deeply into our everyday. Our opening, then, is to exploit its internal contradictions. Our task, as Warren says, is to “drive the system quicker to its own destruction.”

“Afterword: Meeting the Land(s) Where They Are At” Indigenous and Decolonizing Studies in Education (2018)

In this expansive conversation, Erin Marie Konsmo and Karyn Recollet reflect on how colonization enforces ableist notions of purity and normativity on Indigenous bodies and lands, while enacting violence that in itself is disabling. “For many of my queer, two-spirit and trans kin, disability, illness, and sickness are a part of our experiences of colonialism, including when we are on the land or water,” Konsmo explains.

For Konsmo and Recollet, Indigenous resurgence and land defence movements must centre and protect the lives of human, plant, and animal relatives who are deemed “damaged goods” by essentialist purity narratives – from Mad and disabled people to drug users, to animal kin dwelling in city dumps, to plant medicines growing in the rubble of extraction. Their harm reduction-informed approach of “meeting the land(s) where they are at” models a world where all bodies and beings are inherently valued.

The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning & Black Study (2013)

Stefano Harney and Fred Moten’s The Undercommons is a rebellious collection of essays that offers sideways answers to some of the questions that emerged in this reading list: in Dr. Abdillahi’s words, “What does it mean for us to enact madness, to animate madness, to animate refusals, to animate life, to animate choosing our comrades?” And how do we create and sustain life within systems and institutions from which we are unable to fully disentangle?

To contradict our opening remarks, if disability justice is a destination, it would be what Jack Halberstam calls, in his introduction to The Undercommons, the “wild beyond” – a place beyond the strictures and structures of the current order. As Harney and Moten remind us, the place “beyond the beyond” already exists. To get there, Halberstam writes, “we have to give ourselves over to a certain kind of craziness,” a craziness that allows us to reach through the cracks of this world into the next. Disability justice asks us to move together, leaving no one behind, toward the wild beyond. May this reading list point the way.