At a 1997 Free the Media Teach-In, Zapatista Subcomandante Marcos told attendees they had three choices. Option 1: decide nothing can be done against powerful media corporations. Option 2: say all media is lies and close your ears. “But there is a third option that is neither conformity, nor skepticism, nor distrust,” he advised. “It’s the option to construct a different way.” That’s a very tall order. There aren’t many material resources at the grassroots. But there is a wealth of experience and solidarity around the globe, a common sense of mission and, among the most enduring examples, a seamless blending of grassroots theory with grassroots practice. With that in mind, here are a few of the guiding voices that speak to me on the question of how to successfully construct and maintain the third option.

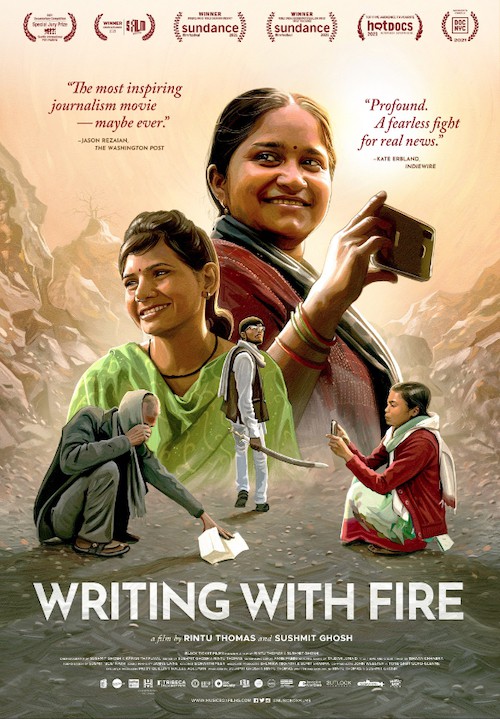

Writing With Fire

Zane Ibrahim, founder of South Africa’s Bush Radio, observed that community media springs up where there’s oppression. It stands to reason, then, that Uttar Pradesh – home to India’s highest number of cases of violence against women and, in particular, Dalit women – is also home to Khabar Lahariya, a thriving grassroots media outlet launched by Dalit women. “But they won’t last for long,” a journalist’s husband predicts early in Writing With Fire. Spoiler alert: he’s wrong. Filmmakers Rintu Thomas and Sushmit Ghosh follow the news team as they blaze their way past doubting husbands, dismissive officials, mansplaining male journalists, the burden of women’s double day, and the ever-present threat of violence – straight toward a successful digital transition with over 500,000 online subscribers and tens of millions of YouTube views. It’s a master class in sustaining and growing alternative media while remaining rooted in the community. Watch and take notes.

People’s declarations and handbooks

I’ve always felt the best of alternative media praxis is found not in books, but in myriad declarations, constitutions, volunteer handbooks, and mission statements. Such documents do more than observe and explain – they educate and mobilize. Briarpatch’s founding verse, for example, is “We all are getting wise, we have to organize!” Some 20 years later, the People’s Communication Charter was gradually compiled by a plurality of networks and movements through the 1990s. It lays out the core concept that all people have a right to participate in making media, free of commercial and government control, in their own languages and localities. If activists were still building this document today, UNDRIP’s Article 16 on Indigenous media rights would fit in well. In another example, the World Association of Community Radio Broadcasters’ Kathmandu Declaration identified community media as an act of “progressive social change and social justice.” The declaration provided proof of concept through handbooks like Women’s Empowerment and Good Governance through Community Radio and The African Community Radio Manager’s Handbook. More recently, Radio Regen’s Community Radio Toolkit offers guidance on community accountability and accessibility, applicable to any medium. These are just a few nuggets. Warning: their online presence is often fleeting. Seek out, download, and save now.

“The Art of Aerialists: Sustainability of Community Media”

Bolivian writer, filmmaker, poet, and media activist Alfonso Gumucio Dagron has long been my go-to on what he calls the “puzzle” of alternative media sustainability. This 2003 paper is just one of his works that grew from 50 case studies gathered in 2001 for the Rockefeller Foundation. The original assignment involved helping donor agencies define and evaluate community media projects. But Gumucio Dagron didn’t stop there. Working independently, he dove deeper and turned the research on its head to serve not just funders, but alternative media practitioners. Two years later, he presented “The Art of Aerialists: Sustainability of Community Media” at a gathering of the OUR Media/NUESTROS Medios network. “We need less accountants and more sociologists to evaluate the impact of alternative, participatory and citizen’s media,” he wrote. In this and other follow-up works, he stresses that even the most financially durable media project with the largest audience can’t be counted a success if it loses its community participation and political mission. In hard times, it’s the friends made, networks nurtured, allies gathered, and solidarities forged that sustain alternative media.

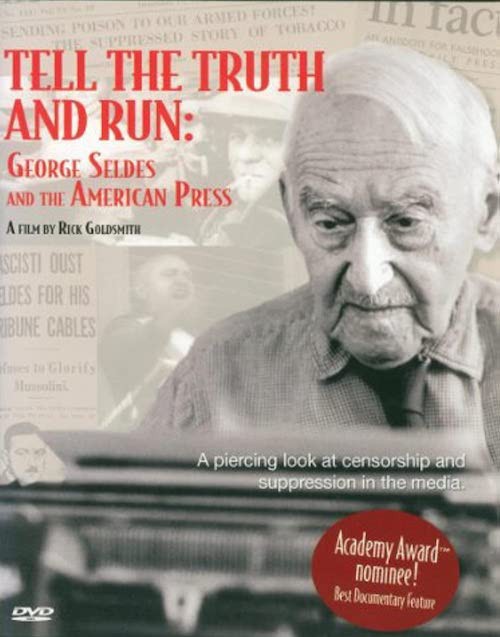

Tell the Truth and Run: George Seldes and the American Press

Whatever you make of George Seldes, he’s definitely an entertaining, provocative voice on topics of media, both mainstream and alternative. He did it all, to the max, saying, “If you can make it to the magical age of 90, all your sins are forgiven.” Rick Goldsmith interviewed Seldes at age 98, and released the film Tell the Truth and Run one year after his passing in 1995. Among Seldes’ self-admitted sins was falling for American propaganda as a war correspondent – until he snuck across enemy lines and discovered war is murder by another name. In 1940, he and his wife Helen (Wiesman) Seldes launched In Fact, an independent newsletter born of their deep disillusionment working for corporate-controlled newsrooms. The Seldeses would equate to today’s bloggers – rugged individualists buoyed by the confidence of white privilege more so than a community base. Still, what they accomplished for the social good was remarkable. One of the first newsletters, for example, exposed Big Tobacco’s efforts to hide their products’ link to cancer. For the next 10 years, In Fact’s unflinching investigations amassed thousands of subscribers and an entourage of FBI snoops. Though embodying voices past, Tell the Truth and Run remains a timeless lesson in the relentless pursuit of speaking truth to power.

Indigenous Media Arts in Canada: Making, Caring, Sharing

Let’s end with something brand new. Hunkpapa Lakota artist/scholar/provocateur Dana Claxton of Wood Mountain Lakota First Nation in Treaty 4 territory has a book coming out this spring, co-edited with Ezra Winton, who helped bring Cinema Politica to life. With an advance copy from this dynamic duo in hand, I can tell you the single-paragraph format of this reading list won’t do justice to the debates, dialogues, despairs, and dreams of the 21 contributing authors. The opening chapter captures a free-wheeling conversation between Danis Goulet, Tasha Hubbard, Jesse Wente, Alethea Arnaquq-Baril, and Shane Belcourt at the 2017 imagineNATIVE Film + Media Arts Festival. They riff on lame stereotypical scripts, false ‘consultation,’ and other daily aggravations of working in a settler-dominated film industry that have left them “frustrated and deeply hungry for a new era in storytelling that would better reflect [their] realities.” The next 12 chapters light a fire for that new era, weaving artistic and technological innovations with the long arc of Indigenous ways of knowing and storytelling. The collection ends with a powerful takeaway from the editors: “The knowing has arrived at the door – the doing needs to open with generosity and commitment.”

_780_520_90_s_c1.jpg)