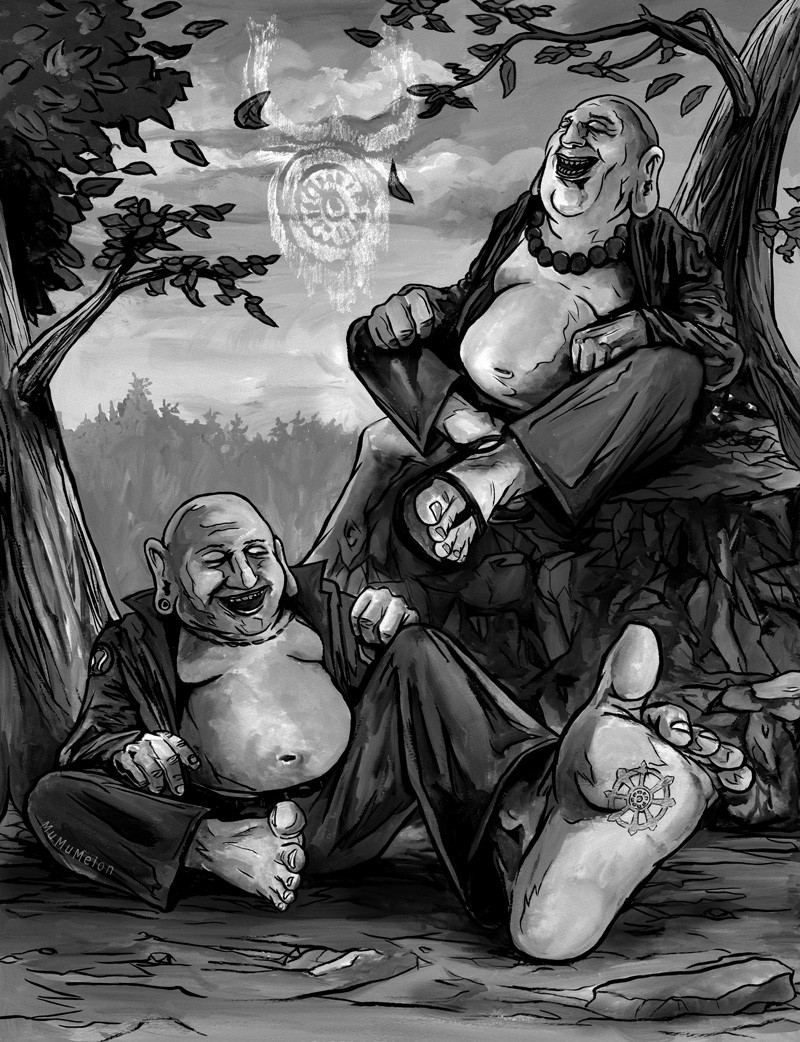

A philosophical storm has been brewing (in its quiet, Buddhist way) in sanghas, meditation groups, magazine articles and monasteries across the continent.

A friend once commented that I’d be a backslider in any religion. My recent dabbling in Buddhism suggests that may well be the case.

While I have long been a devout atheist, I am intrigued by human spirituality and the many manifestations of it I’ve encountered. Whether taking part in a shamanic trance ritual in northern Ghana, attending a startlingly powerful Friday prayer ceremony at a mosque in the Gambia or participating in transformational Aboriginal sweats, the ways we humans cope with being alive through our sacred rites fascinates me. As Leonard Cohen puts it, perhaps religion is indeed the ultimate “deep entertainment.”

Given all of this, Buddhism, perhaps the world’s only non-theistic religion, has always held particular interest for me. Besides not requiring adherents to check their critical thinking abilities at the door, Buddhism also emphasizes compassion, patience, loving kindness, equanimity and generally being no crazier than necessary—all areas I could use a little brushing up on myself. (Just ask my wife.) Plus, Buddhism always seems to line up on my side of the political fence—the Dalai Lama describes himself as “half communist, half Buddhist.”

But after undertaking a personal exploration of Buddhism that included regular morning meditation, weekly sangha (a sort of loose Buddhist community) meetings and reading both ancient and more contemporary Buddhist writings, I found myself backsliding once again.

The elephant in the room

For the last several years, a philosophical storm has been brewing (in its quiet, Buddhist way) in sanghas, meditation groups, Buddhist magazine articles, and even Buddhist monasteries across the continent. Thus far, though, the storm has remained largely unacknowledged. The elephant in the room here is the emergence of a Western Buddhism that downplays elements of traditional Buddhist dogma. One reaction from some traditionalists to this newly packaged Buddhism has been the reassertion of a troubling brand of Buddhist fundamentalism.

Buddhism spans 2,500 years, and over that vast period of time it has reached into every nook and cranny of Asia, lately establishing beachheads in many other parts of the world. While estimating the exact number of Buddhists is complicated by political factors, the lack of a central “Buddhist” authority, and in some locales a pretty flexible idea of religious membership, the number of Buddhists is generally put between 500 million and a billion, with adherents in virtually every country in the world.

As with all religions, Buddhism has mutated as it spread, often incorporating local beliefs and adapting to host cultures and societies. Chan Buddhism, which originated in China in the sixth century and incorporates elements of Taoism and other Chinese philosophies, is significantly different from the brand of Mahayana Buddhism that Bodhidharma brought with him to the Middle Kingdom from India. And then there is Pure Land Buddhism, with its emphasis on devotional prayers to Amitabha, another Buddha who preceded the Siddhartha we know as Buddha by “eons.” Amitabha guarantees the devout an eternal life in a “Western Pure Land of Ultimate Bliss.” Pure Land cobbled together elements of Buddhism and Asian folk beliefs in a popularized package that has made this sect all the rage in much of East Asia, especially Japan. It is presumably cohabiting in Japan somewhat uncomfortably with its austere cousin, Zen, which evolved from Chan Buddhism in the 12th century.

Indeed, almost from the beginning there has been no consensus about doctrinal correctness and proper practice within Buddhism. Only 500 years after Buddha’s death, there were at least 18 distinct schools battling (usually, but not always, figuratively) over who possessed the “authentic Buddhist path.”

Buddhism has grown rapidly in popularity in the West in recent years. Between 1990 and 2000 the number of professed Buddhists in the U.S. increased by 170 per cent, making it the fourth largest religion in the country, with about 300,000 adherents. It is not surprising, then, that Buddhism in the West has begun to reflect the cultural context of its new home.

But those who sought in the wisdom and teachings of the Buddha a personal and social guide for greater happiness, understanding and compassion were often surprised to find a doctrinal core to Buddhism quite at odds with its popular image in the West. The ideas of samsara (reincarnation) and karma (the idea that all deeds, past and present, actively create future experiences and incarnations), were particularly jarring, and have generally been downplayed or reinterpreted by American and Canadian Buddhists, seemingly in keeping with the Buddha’s advice to “Doubt everything. Find your own light.”

Given many Westerners’ experience with Christian fundamentalism and its fossilized social and political attitudes, you could almost hear them ask, “Whoa, do we really want to trade one set of superstitions for another?” To embrace Buddhist principles, are we required to swap one explanatory fiction for an even more arcane way of denying death?

Many thought not, and the result has been a general soft-pedalling in the West of the “whole karma thing.” Popular Buddhist writers such as Pema Chödrön choose simply not to deal with the issue, while others, such as Stephen Batchelor, openly reject the entire idea of karma and assert that people can be “Buddhists without beliefs.” David Brazier, one of the leading Western interpreters of Buddhism, puts it simply: “The whole teaching of rebirth is unnecessary to a proper understanding of the Four Noble Truths.” Besides, he asserts, the concept of rebirth “is basically a Hindu idea, not a Buddhist one.”

It is no shock, then, that we are beginning to see a sharp reaction from Buddhists steeped in traditional practices and orthodox beliefs. Among the most vocal critics of karma-free dharma (spiritual practice) are Dzongsar Jamyang Khyentse, author of the marvelously titled What Makes You NOT a Buddhist (so much for Buddhist ecumenicalism), and Bhikkhu Bodhi (né Jeffrey Block). Bhikkhu Bodhi lays out the argument against any liberalization of Buddhist dogma quite clearly: “The aim of the Buddhist path is liberation from suffering, and the Buddha makes it abundantly clear that the suffering from which liberation is needed is the suffering of bondage to samsara, the round of repeated birth and death.” Bodhi concedes that Buddhist practice can serve to eliminate the “sorrow, tension, fear and grief” of daily life, but that “to downplay the doctrine of rebirth and explain the entire import of the Dhamma [also known as Dharma, the teachings of the Buddha] as the amelioration of mental suffering through enhanced self-awareness . . . risks reducing it in the end to little more than a sophisticated ancient system of humanistic psychotherapy.”

The label “humanistic psychotherapy” would appear to fit. In fact, many of the most influential Western Buddhist writers (including Jon Kabat-Zinn, Jack Kornfield, Mark Epstein and Caroline and David Brazier) are themselves practising psychotherapists. Most of these writers choose to emphasize karma and the “law of causality” (the idea that what you are is a direct result of past actions) not in the context of the traditional three lifetimes, but in terms of this lifetime, which we know we occupy. “Karmic traces,” these theorists tell us, are not holdovers from a previous misspent life. They are patterns established, usually unmindfully, in this lifetime that lead to habituated actions and further suffering—again, in this lifetime. Their focus is not on an escape from the cycle of rebirth and the extinction of feelings, but on the day-to-day task of finding happiness and cultivating meaningful ways of engaging in a world that needs all the loving kindness, compassion and right action we can muster.

Bill Gates’ karmic reward

For me this growing divide within Buddhism became personal two summers ago while attending a retreat at a Theravadan monastery near my home. During an afternoon Dharma talk, an earnest young guest asked about the concept of merit. In Buddhism, merit is the idea that good deeds, acts or thoughts carry over into and shape a person’s next birth. “Given the complexity of the law of causality,” he asked, “how do we know which actions earn us the most merit?”

“Well,” the monk replied, “we can never be sure. But while you gain some merit by small deeds, like helping a line of ants over a barrier, you are sure to amass greater merit by working for an organization like Mother Teresa’s than, say, with a mass murderer.”

The questioner was not placated. “But maybe I would gain more merit working with the murderer because he has greater need for my help.”

At this point I sort of zoned out. I’ve never been particularly interested in debates along the lines of how many angels can dance on the head of a pin. But I snapped back to attention when I heard the monk remark solemnly, “Bill Gates performed some act of great merit in his previous life. That is why he is the richest man in the world.”

I looked closely at the monk, hoping desperately he was kidding. He wasn’t.

“Buddha used the idea of merit,” the monk went on, “to explain why there were such disparities in wealth and privilege.”

Now in Theravadan tradition, a courteous novice wishing to converse with a monk holds his hands together as in prayer and gently bows toward the monk to be recognized. I can’t remember whether or not I got my hands together before I practically lunged across the table to interject, but I certainly got recognized.

“Surely,” I fairly spluttered, “you would agree that social inequity and poverty are man-made creations, constructed and maintained by social and economic structures of our own devising, not some hangover from a previous life. That sort of argument just provides a legitimization, an apology, for inequality.”

The monk most assuredly did not agree. In fact, while acknowledging that it was okay to “examine the teachings critically,” he cautioned me that it was “a mistake to abandon key elements of Buddhist dogma to make it more palatable.” Moreover, he admonished, karma was pretty basic to Buddhism. “Some things come down to faith,” he explained. “There is a place for faith in Buddhism.”

I desperately wanted to continue the discussion and to point out that doing good deeds to score merit points so as to ensure a better life next time around didn’t exactly seem consistent with the spirit of Buddhist teachings as I understood them. But I was aware of the discomfort building in the room (which had suddenly become all too aware of the ghostly pachyderm in its midst), and, reminding myself of the basics of Right Speech (the third of the eightfold path commandments; namely, to speak at the right time, with affection and “with a mind of good will”), I chose to shut up. But the damage was apparently done. I was not a popular guy at the monastery for the rest of my stay.

Some months later, Hugh, a sad little former monk recently returned from Thailand, found his way to our modest sangha. One afternoon Hugh and I were sitting at a café when I saw a magnificent steam locomotive with vintage rail cars in tow chuffing along the rail line a hundred meters away. I was thrilled. Hugh didn’t even look up.

We were in the middle of a discussion about my skepticism surrounding samsara and the whole idea of karma and rebirth. “If you don’t believe that Buddhism will lead you to an escape from samsara and suffering,” he asked, “why in the world would you practice it?”

“Because it provides me with a path to a more fulfilled life,” I replied. “And a basis for a saner, more functional society. Why else?”

Hugh just looked at me in genuine puzzlement. And I at him. Here was the schism writ small. Then I looked beyond him to the beautifully restored locomotive, resplendent in its shining black paint and deep red trim.

Since then I have encountered the same tensions within the small meditation group to which I belong. Some of us are there to find ways of enriching this life, while others are working hard to escape the next one. Unitarians and Southern Baptists would have an easier time finding common ground with one another. But as the dialogue heats up, surely Buddhists, however we define that concept, must apply the same tolerance, understanding and compassion to people in their own spiritual tradition as they do to anyone else.

As the history of religious strife sadly demonstrates, however, this may be easier said than done. While I suspect this debate won’t end anytime soon and may turn outright ferocious at times, it will, I hope, eventually bring Buddhism into the current era and result in a synthesis that is durable and inclusive. Sol Hanna, member of the Buddhist Society of Western Australia (who lists his occupation as “dharma bum”) put it quite nicely in a posting on their website:

[L]ooking at the social tensions occurring within Buddhist communities, it seems to me that all difficulty and controversy relates to people having a static view of what Buddhism is and how it is practiced at a time of rapid technological and social change. . . . Personally I don’t see this as problematic, and indeed, I am optimistic that we are going to see quite a bit of convergence within Buddhism over the next few decades. Much that is out-dated and superstitious will fall by the way-side (because basically it doesn’t work, and will be seen as such) and that which is practical and useful will come to the fore.

Which is which will be the source of spirited debate, but surely we can look to Buddha’s own words as we enter this process:

Do not believe in anything simply because you have heard it or because it has been handed down for many generations or because it is found to be written in religious books or merely on the authority of your teachers and elders. But after observation and analysis, when you find that anything agrees with reason and is conducive to the good and benefit of one and all, accept it and live up to it.

Amen.