I am a rural queer. I was born and raised in a small town that has always reminded me of Barbara Kingsolver’s description of “a wrinkle on the map that lies between farms and wildness.” This line from Kingsolver’s Prodigal Summer has always appealed to me because it captures perfectly the way woods and cows bracketed my childhood movements. Many people assume that queers cannot live well in the country. They think that our neighbours hold prejudices that are unique to rural spaces and that there just aren’t enough queers in the country to find love and community in any case.

When I moved from a small town in rural New Brunswick to a bigger city in central Ontario, for instance, people assumed that I’d moved because I wanted to connect with “my community.” People were sometimes surprised to find out that I left a vibrant queer community in the Maritimes, and that I lived a good, queer life in a small town. I have since moved back to New Brunswick, and I intend to stay here and stay queer.

I’m not denying that oppression exists in rural communities. I live on land stolen from First Nations people, in an area where most people have far too little money. And many queer folks have had bad experiences in rural areas. Homophobia and heterosexism are alive and well here. The thing is, I am reluctant to use these experiences as evidence that hatred and oppression are worse here. It lets city folks off too easily, and it treats rural people and the communities where we live as homogeneous and uncomplicated. It also denies that oppression is systemic. It might look different from place to place, but oppression doesn’t stop at the borders of Quebec or Maine, or even at the ocean’s shore.

Needing queer stories

A few years ago at a conference, a researcher named Julia Sinclair-Palm told me about doing research with trans youth. The research looked at the impact of hearing repeated stories about transphobia and prejudice and the effect this had on trans kids. Sinclair-Palm highlighted a TED Talk by Chimamanda Adichie called “The Danger of a Single Story” in which Adichie warns that when we create a single story, it shows “a people as one thing, as only one thing, over and over again, and that is what they become.” Sinclair-Palm’s research explores how stories of violence impact the stories that trans youth construct for themselves.

I can’t stop wondering about the impact of single stories on rural queers in particular. What does it do to those of us bracketed by cows and woods to hear time and time again that rural communities hate queers? What happens to us queers when this is the story we keep telling about ourselves and the people around us? I worry that we foreclose opportunities for good queer lives and that we do our neighbours an injustice.

A feminist researcher and friend of mine, Sue McKenzie-Mohr, talks about people who are “living well,” even after they have faced significant hardships. I love this concept because it refuses to see trauma without resilience and it draws attention to the nuances of living on in spite of oppression.

I needed to hear stories of queers living well, in order to continue living well myself. I wanted to hear stories that would inspire me to write my own story better. I was interested in role models and the real humans who live in the country. I wanted to learn how they do it so that I could continue to do it too.

Sharing Stories

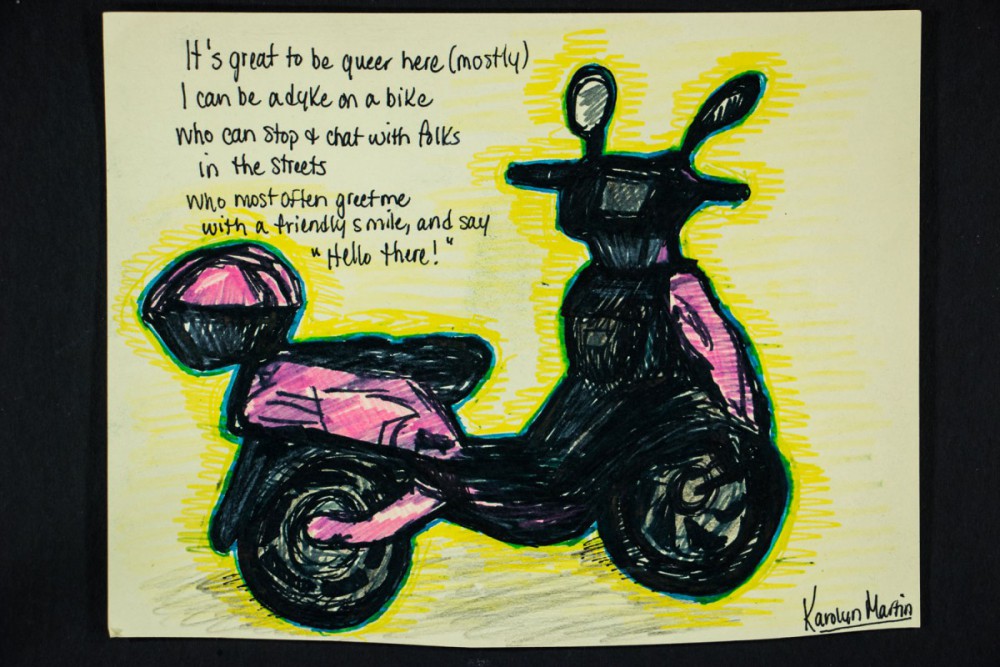

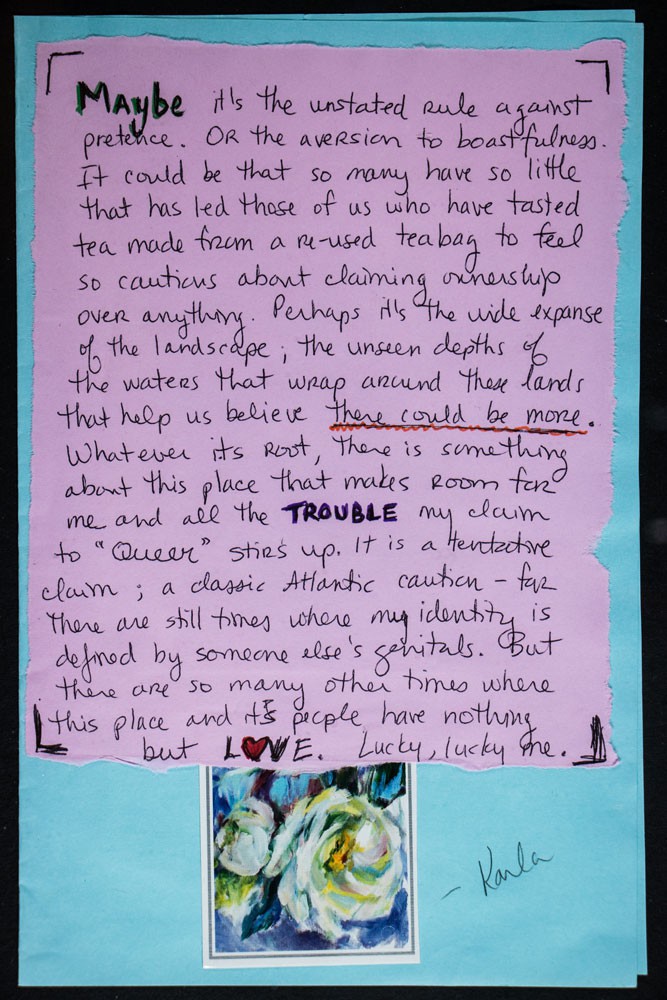

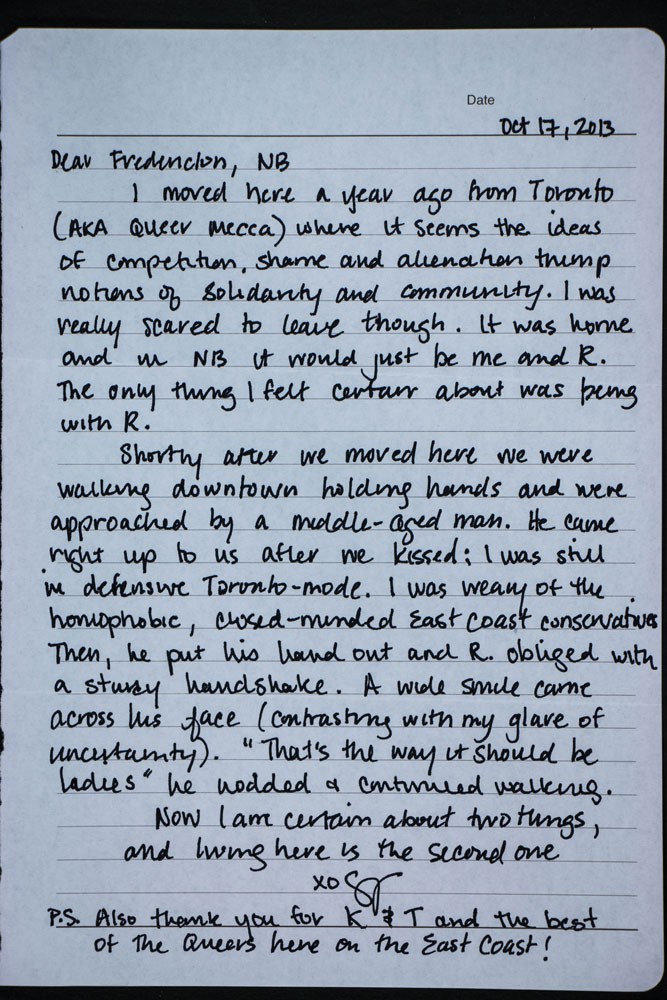

Slanted Near the Atlantic: Love Letters to the East Coast is the community art project that grew out of my desire to hear stories of queers living well in the country. The goal of the project was to have people submit letters about their relationship with the East Coast, where we’re mostly rural and where even our cities look like small towns to urbanites from away. I got the idea from an art activist and educator, Carolyn Jervis, who developed a community art exhibit called Love Letters to Feminism. I chose the love letter medium because I had the benefit of seeing the impact of Jervis’ choices – the adoring letters, the love-hate letters, the uncertain letters. Love letters opened up the possibility of expressing complicated relationships with ideas, places, identities, and people. The intimacy of the letters in Jervis’ project left me craving more.

The letters I received for Slanted were moving, intimate, funny, and complex. They told stories of queer lives that were good – not perfect lives, just good ones, lived well along the Atlantic coast at one point or another. When I asked contributors why they’d chosen to write a love letter, I got responses that were as beautiful as the letters themselves.

A self-identified queer woman living in Alberta wrote: “I wrote my love letter to the Atlantic because I aspire to live a queer life that works against the demands that capitalism, ableism, patriarchy, racism and other oppressive systems put on our lives. I believe that this pull for a different life emerged from living on the East Coast. Not from a romanticized small-town life, but from the everyday challenges of trying to live well in a town where you mostly know everyone, where people are struggling economically, and where many people worked to accept my ‘weirdness.’ My love letter to the Atlantic was not a disavowal of the challenges of living a queer life there, but an opportunity to consider how my love for the East would hopefully create a bit more space for living differently.”

The amazing part of the letters is that a lot of them, like that one, came from “away.” Over half of the letters I received were from people who have moved to larger cities like Toronto, Edmonton, and New York. In Another Country: Queer Anti-Urbanism, Scott Herring writes about such stories, saying: “I hate that no queer in New York has ever had to apologize to other queers for wanting to live there, unlike those of us who did not wash up on its shores.” The letters in Slanted not only refuse to apologize but actually celebrate rural life.

These letters highlight the voices of rural queers who are often elided and silenced in dominant narratives about rural culture. I have received approximately 50 letters so far, and I have staged the exhibit twice for public audiences. When people come to exhibits, they have an opportunity to write letters on the spot, and I leave spaces in the exhibit where people can add completed letters to the display right away. It’s an opportunity for people to fashion their own stories in an environment where rural queer life is celebrated. It’s a cherished opportunity, and a chance to see role modelling at work, because people actually use these stories as inspiration for their own.

Writing and promoting stories of living well as country queers helps debunk the myth that oppression is limited to specific geographical areas. It has also helped participants share the message that queer lives are not necessarily better lived in urban centres; they’re good here, too. Sharing these stories not only affirms my deep, nuanced, joyful, and cautious love for the Atlantic but also shows us that this place can hold a lot of love.