Arthur Dennyson Hamdani

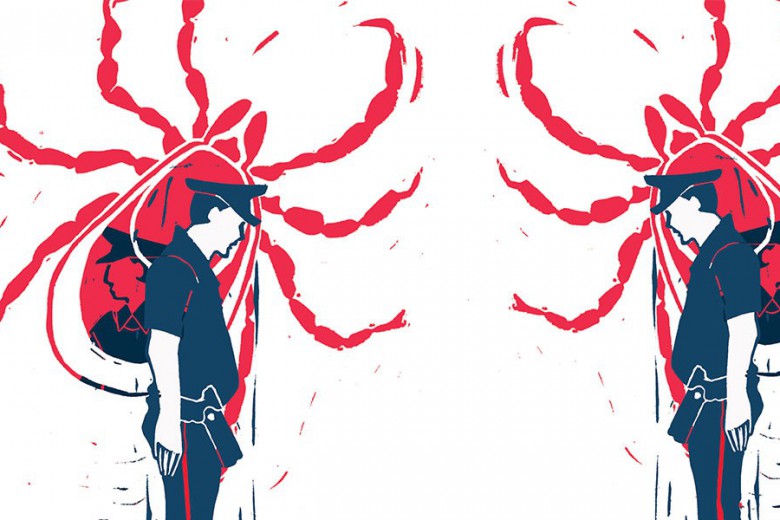

Canada Goose is a well-known luxury parka brand that has distinguished itself with its “Made-in-Canada” claim. What many do not know is that these parkas are largely sewn together by the hands of immigrant women – many of them Filipino, Indian, and Chinese – who have also stitched together a momentous union movement in Winnipeg’s historic garment industry over the past six years.

In December 2021, the workers at Winnipeg’s Canada Goose facilities voted overwhelmingly to unionize. Eighty-six per cent of workers voted in favour of forming a union under Workers United Canada Council (WUCC). This historic victory was achieved by and for a largely immigrant and female workforce that persevered throughout a tumultuous union drive despite facing hostility and precarity in their workplace. This is their story.

Working conditions at Canada Goose

Before forming the union, workers described a climate of fear in Winnipeg’s Canada Goose facilities. Reporting in outlets such as Canadian Dimension and Vice exposed union-busting and unsafe working conditions at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic. Workers have also experienced aggressive and disrespectful behaviour from management. Rose*, a shop steward at Canada Goose, recalls, “Before the formation of the union, the management and supervisors acted like the lords. Scolding employees in public was common.”

As the workers describe, “acting like lords” translated to managers engaging in power-tripping. Workers could not question management or express their concerns about workplace conditions. As Rose shares, “No, we had to follow [their rules]. We workers did not have a voice.” Linda*, a sewing machine operator, tells us, “You couldn’t talk back to them. Like you just want to cry. You couldn’t report them. Who could you report them to?”

Along with the way that management treated them, workers felt that they were disposable as they saw their co-workers lose their jobs easily. They also felt that their ability to keep their jobs was determined by how efficient they were. Seeing other workers losing their jobs made Jane*, a sewing machine operator, nervous about her own job security. “I had this one co-worker who was called [to the office] and then was escorted out. That was it, they couldn’t do anything. So, every time we got called to the office, we got nervous,” she recalls.

“I was determined to form a union for us. However, [my co-workers] were afraid. So, I alone, with the organizer, would go to their houses.”

The workers had many other issues with the company, including unpaid breaks that lasted less than the legally mandated 30 minutes and stagnant wages. Workers could not go on compassionate leave, which was important to them as immigrants who may need to return to their home countries for family emergencies. Instead, workers were encouraged to quit and reapply for their jobs when they returned to Canada. During the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, a report from Vice revealed health and safety violations in the facilities, such as having no personal protective equipment or sanitation for workers.

These conditions at Canada Goose are not isolated; rather they’re symptomatic of the rise in unstable or precarious work in recent decades, especially for racialized, gendered, and immigrant workers. Although unionizing could make their jobs more stable, the very precarity that unionizing could improve creates barriers to participating in unions for marginalized workers.

Forming the union

Confronting these conditions, the workers at Winnipeg’s three Canada Goose facilities began a union drive under WUCC in 2019, starting in the facility located on Mountain Avenue. The union drive was initiated because Vivian*, one of the shop stewards, connected with an organizer from WUCC through her community. After asking other workers if they would like to form a union within their facility, workers and organizers began collecting signatures on the union’s application card.

This was not an easy process: workers involved in the union drive devoted a lot of time and effort after work toward convincing their fellow workers that unionizing would be beneficial for their collective protection. Vivian, as a shop steward, was involved in the union drive and recounts how she would accompany the organizer from WUCC after her shifts even when she was tired. “I was determined to form a union for us. However, [my co-workers] were afraid. So, I alone, with the organizer, would go to their houses.”

Canada Goose used various tactics to suppress the union drive in its Winnipeg facilities. One major challenge during the pandemic was that one of the union leaders was temporarily laid off because of factory closures and, unlike other workers, did not receive a call to return. This led to a widespread, successful social media campaign that brought awareness to the working conditions at Canada Goose, compelling Canada Goose to reinstate the union leader. Not only were union leaders terminated, but workers were actively encouraged by management to sign letters objecting to the union drive. This led the union to successfully file an unfair labour practices (ULP) complaint against Canada Goose which, in December 2019, resulted in a $2,000 fine.

Members of Workers United Canada Council and Canada Goose Union pose with Manitoba premier Wab Kinew at the 2025 Labour Day celebration in Winnipeg's Memorial Park. Photo courtesy of the Canada Goose Union.

Beyond being faced with an actively union-busting employer, workers faced the challenge of recruiting their co-workers. Many were often afraid to get involved in the union drive for fear that they would lose their jobs. Martha*, a shop steward who was involved in union leadership in past jobs, shared her hesitancy to organize at Canada Goose. She tells me, “Most of them are newcomers so they are depending on Canada Goose. […] I stayed away from organizing. I don’t want people to run out of jobs because […] that’s the only means of their living,” she says.

At first, workers were hesitant to support the union drive because they were concerned about the deductions from their pay for union dues. Most workers were being paid minimum wage and as immigrants, their pay not only supported themselves and their immediate families, but also their families in their home countries through remittances.

The union faced other challenges such as expanding their union drive to the other two facilities in Winnipeg and changing their recruitment strategies because of the pandemic. Because of COVID-19 restrictions, organizers recruited workers by leaving union application cards in workers’ mailboxes and talking to them over the phone.

As a result of tireless recruitment efforts from union leaders, workers eventually came to support unionizing. A central part of the union drive was building a network of relationships and trust between the union and the workers. For example, Vivian shared that in every production line, she would identify potential union leaders who could then recruit other workers in their respective lines. Rose, who used a similar strategy based on ethnocultural lines, recounted, “I recruited groups of Chinese workers, groups of Korean workers […] I had connections who were Indian, whatever ethnicities there were.” Building solidarity across ethnocultural lines and the shop floor was essential to the success of the union drive. The organizers at WUCC also ensured that union leaders were trained in organizing to build their confidence in talking to other workers.

Beyond the Canada Goose facilities, the union received messages of solidarity during their online campaign to reinstate one of the union leaders. Local labour organizations such as the Association Of Employees Supporting Education Services and the Manitoba Federation of Labour showed support by sharing the campaign online. Groups in the U.S. such as New England Joint Board UNITE HERE and Massachusetts Jobs with Justice also marched at a Boston rally in 2021 to show solidarity with Canada Goose workers in Winnipeg. This form of coalition building helped the workers feel emboldened during the union drive.

The union today

Through building these networks of trust and relationships within the workplace and with other labour organizations, workers at Winnipeg’s Canada Goose facilities overcame these barriers and successfully organized a union in their workplace. Since 2022, they have been under a collective agreement and have a voice in shaping their own working conditions through their shop stewards. As Jane points out, “because we are union members, we can now speak. Whatever we want to fight for, we can now voice out. We now have something to lean on because we have a union.”

The union has also ensured that its shop stewards come from diverse ethnocultural backgrounds, with one shop steward, Tina*, sharing that the union had Filipino, Chinese, and Ukrainian representatives “because those are the major ethnic groups in Canada Goose [factories]."

Workers now feel more secure in their jobs than ever before. Because they fought to have bereavement leave and vacations included in their collective agreement, workers do not have to leave their jobs to return to their home countries as they had done before. Today, the union represents their interests within conflicts and grievance procedures. Workers believe that unionizing has balanced the unequal power relations between them and management. As another worker, Hannah*, explains, “The impact of the union is really huge for us in keeping us feeling secure [where] we are working happily. It’s not scary where a small mistake immediately gets you fired […] Today, that doesn’t happen because they fight for you.”

Beyond these tangible improvements, having a union has also made a difference through educating workers about their rights, with one worker saying, “It is very helpful for me to get to know more [about] the [collective] agreement […] so that when we’re just in trouble, we can speak up.” Workers also feel empowered because of their involvement with the union, and for one of them, and it has helped connect them with their ethnocultural community: Julie* shares, “They always see me as their leader. They come to me […] So, I feel like they are more confident in me […] they trust me, and I do feel like I need to help them.”

What makes a difference for the workers at Canada Goose is that they are represented by people with whom they share identities and communities. The women working at Canada Goose were more comfortable bringing their concerns to women shop stewards because they felt that they would have a better understanding of the issues women face. The union has also ensured that its shop stewards come from diverse ethnocultural backgrounds, with one shop steward, Tina*, sharing that the union had Filipino, Chinese, and Ukrainian representatives “because those are the major ethnic groups in Canada Goose [factories]. And some people who speak in Punjabi from India.”

Futures for the movement

The workers at Canada Goose have shown us what can be possible for the broader labour movement in Canada. As work becomes increasingly unstable and more precarious for racialized workers, unions must ensure that these workers, such as those at Canada Goose, are organized and represented by union leaders who understand the specific conditions that immigrant women who make up a large percentage of the workers face. Only through fostering solidarity with marginalized workers through understanding their demands will unions truly be able to fight for the new working class in Canada.

*This article draws on confidential interviews from the author’s Master’s thesis project, funded by the Manitoba Research Alliance. Because of this, pseudonyms are used in place of participant names. Some of these interviews have been translated from Tagalog by the author.

This project would not have been possible without the collaboration of Workers United Canada Council and Canada Goose Union. Funding for this project was provided through the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council grant “Community-Driven Solutions to Poverty: Challenges and Possibilities” administered by the Manitoba Research Alliance.