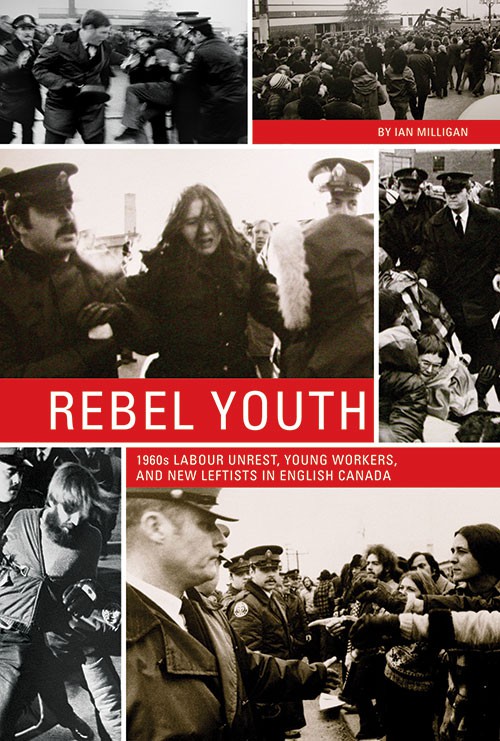

Rebel Youth: 1960s Labour Unrest, Young Workers, and New Leftists in English Canada

By Ian Milligan

UBC Press, 2014

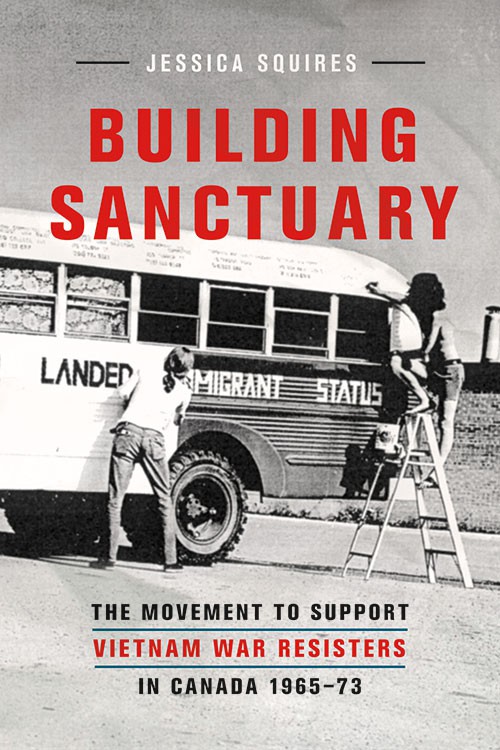

Building Sanctuary: The Movement to Support Vietnam War Resisters in Canada, 1965 -73

By Jessica Squires

UBC Press, 2013

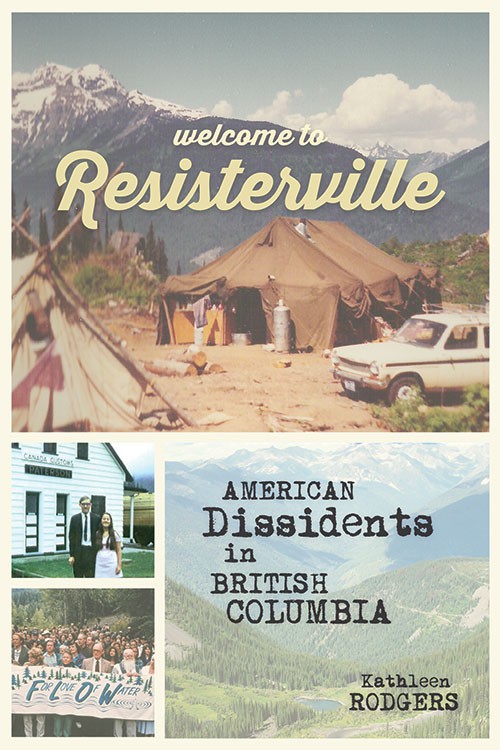

Welcome to Resisterville: American Dissidents in British Columbia

By Kathleen Rodgers

UBC Press, 2014

Almost half a century since the 1960s ended, the decade remains one of the most studied and contested areas of historical inquiry, a high-water point of lefty pride and a right-winger’s bête noire. While the right blames the “permissive” values of the ’60s for everything from teenage pregnancy to 9/11, the decade’s revolutionary potential is often overlooked or misunderstood in the wash of boomer nostalgia that prefers to frame the era in Kodachrome images of Woodstock and the Beatles.

For many Canadians the ’60s simply evoke Trudeaumania and the last time the Maple Leafs won a Stanley Cup.

While stateside, ’60s memoirs could fill libraries, Canada’s ’60s tend to be less celebrated, perhaps owing to the smugness of Canada’s prosaic brand of nationalism. Three new UBC Press titles help fill in some of the gaps by confronting head-on the myths that tout Canada as a “peaceable kingdom” that welcomed refugees from racism and militarism alike (a myth still echoed in various corridors by those who praise as a “peacekeeper” the man who pledged to bring nuclear weapons to Canada, Liberal leader Lester Pearson).

While the ’60s are justifiably viewed as a decade of insurgent youth culture (which continued into the ’70s), we forget, as Ian Milligan points out in Rebel Youth, that campuses were not the only protest hotspots. Indeed, in the 1960s some 87 per cent of Canadian young people went straight from high school into the workforce. There, they challenged what many saw as a quiescent labour leadership coasting on the tails of the entente it had entered with the postwar Canadian state via the Rand formula which guaranteed that union dues would be collected directly by employers and turned over to the union (while unions agreed not to strike for the duration of a collective agreement).

The influx of younger workers contributed to the dramatic rise of mid-’60s strikes (almost 600 from the beginning of 1965 through 1966, with upward of 50 per cent of them illegal wildcat strikes). Many of those strikes were aimed not just at employers, but at union leadership as well. “Thanks to the automatic dues check-off, unions did not have a structural or financial imperative to reach out to their youngest members,” Milligan notes. “It would take the wildcat to recognize the importance of doing so.”

Indeed, picket lines that rejected labour’s top-down structure, demands for improved conditions that earlier generations hadn’t deemed necessary, and the anti-authoritarian ethos marked a shift from the union movement of the prior two decades. Milligan details the attempts by students to reach out to and form alliances with workers. These efforts included some long-forgotten but crucial student-worker campaigns, including the legendary, often violent Artistic Woodwork walkout in 1973 in North York and the 1970 Nova Scotia fishers’ strike at Canso (which almost precipitated a provincial general strike). It’s a potent reminder of labour’s dormant capacity to actively challenge not only its immediate circumstances but also the social structures that perpetuate ruling-class power.

Just as today’s union movement would benefit from Milligan’s provocative historical review, another group facing problems similar to those of their 1960s antecedents – Iraq War resisters seeking sanctuary in Canada – will find Jessica Squires’ Building Sanctuary, an exploration of Canada’s Vietnam-era anti-draft movement, a useful study. In the Canadian imagination, the Trudeau era was a peaceful one that welcomed draft resisters with open arms, when in fact, Canada played a significant though little-publicized role in the provision of war materials, in weapons testing, and in diplomatic cover for U.S. aggression. Likewise, many live under the illusion that the Chrétien government rejected participation in the 2003 invasion of Iraq on principle, when the factual record shows Canada played a significant though low-profile role, one acknowledged by the likes of former U.S. Secretary of State Colin Powell.

Squires’ history is an important reminder that the Trudeau government’s rhetoric about Canada as a “refuge from militarism” was not matched by official policy, from the use of the RCMP and local police forces to harass U.S. expatriates to tipping off U.S. officials when deserters were turned away from Canada. Squires accesses internal government communications that clearly contradict Canada’s smiling public face toward young people rejecting the draft. She also documents the prodigious efforts of support groups that provided counselling, lobbied, and effected changes that eventually opened the borders. She meticulously takes apart the various pieces of the immigration puzzle to show how difficult it was for many to emigrate here rather than serve in the U.S. military or go to jail. In the same manner that they could enjoy college deferments, privileged, middle-class white kids also stood a better chance of acceptance as landed Canadian immigrants under a point system that considered such benchmarks as job offers and education levels. Meanwhile, younger African-American men could not enter so easily. Indeed, the difference between the unthreatening “draft dodger” and the military deserter (usually someone poorer and non-white who had gone into the military because they could not access college or other deferments) determined the demographic of those who eventually were landed in Canada.

Both Milligan and Squires also remind us that the ’60s and early ’70s were not the sole preserve of the young. Indeed, much of what seemed new under that decade’s media lights had in fact been tried before by an earlier generation (including draft card burnings and freedom rides during the 1940s). This is clear in the multi-generational composition of anti-draft support groups but also in the makeup of a key destination for many war resisters: B.C.’s West Kootenays.

Kathleen Rodgers’ Welcome to Resisterville explores how American dissidents seeking an alternative way of life from a declining industrial empire trapped in endless cycles of war and racism took up residence in rural B.C., often building on the traditions already begun by previous generations’ exile groups (namely, the Quakers and Doukhobors). It also gives lie to the idea that back-to-the-landers were escaping from the world rather than choosing proactive, intentional means of living differently. Indeed, her book explores how American dissidents brought with them a loving idealism that often contributed to a long tradition of resistance, from participation in a variety of crucial environmental campaigns to building alternative civil society institutions that would enmesh their progressive values in schools, food co-ops, and women’s centres.

In a refreshing reminder that the activist members of the ’60s generation did not all disappear into yuppie consumerism, Rodgers is able to trace the decades-long impact of this group in a concentrated area (some 40 per cent of American draft resisters who chose to stay in Canada after the 1976 amnesty settled in B.C.). Just as there was mistrust and suspicion of newcomers in the ’60s and ’70s, the issue remains contentious today. An international controversy erupted in 2004 when it was revealed that the town of Nelson, B.C. planned a statue commemorating Vietnam resisters and Canadians who worked to resettle them. The idea was scuttled, but the controversy did not prevent residents from carrying on the generations-old tradition of welcoming war resisters, with numerous Americans who had been welcomed in the ’60s opening their own doors to those resisting the Iraq War.

All three of these books serve as important reminders that history is not easily bookended by the arbitrary markers of decades and is instead a living process that holds new discoveries for those willing to dig deeper and learn vital lessons for today’s struggles.