First Nations, Ojibwa, Blackfoot, Indian, Aboriginal, Treaty, Half-breed, Cree, Status Indian. These are all familiar English words, but none of them are the names by which we, the various Indigenous Peoples, called ourselves in our own languages.

How many Canadians have heard these names: Nehiyaw, Nehiyawak, Otipemisiwak, and Apeetogosan? These are who I am because these are the names my grandparents used. Even “Métis” is not the name people called themselves in Manitou Sakhahigan, the community in which my dad, Tony, was born and raised. And even that place is primarily known by its English/French name “Lac Ste. Anne.”

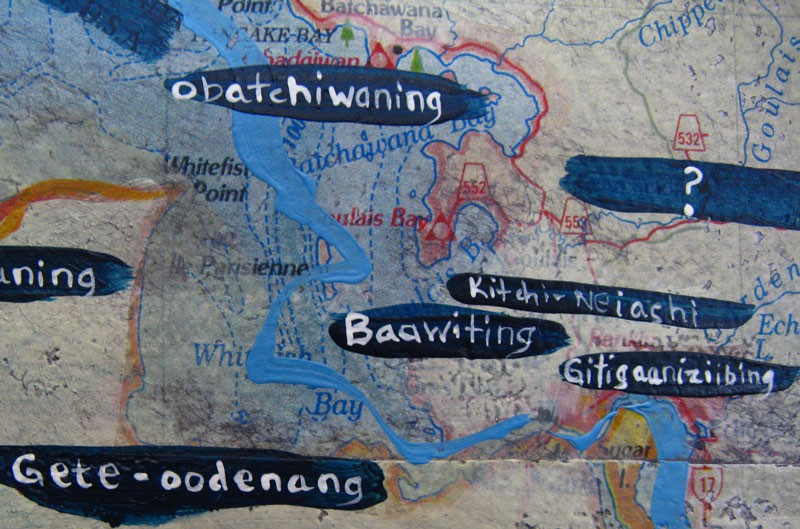

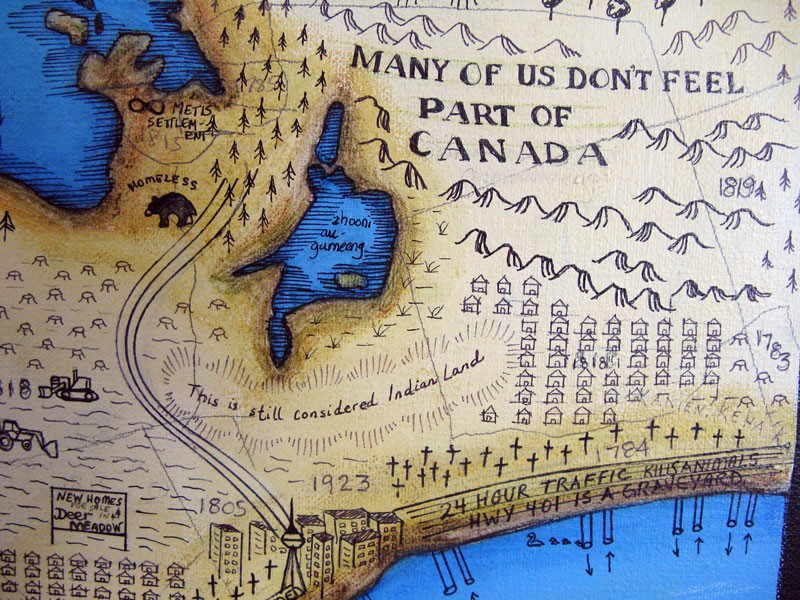

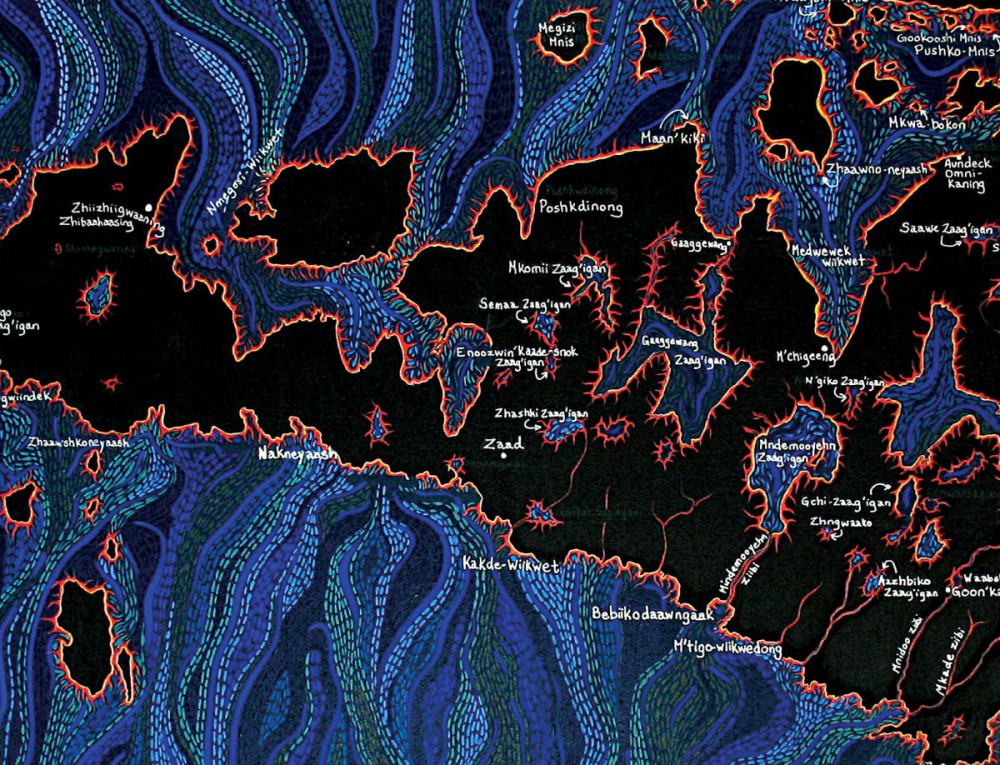

Place names are a complex issue in Canada. Some argue that Canada reflects its Indigenous roots in many place names derived from Indigenous languages, even though the origins and meanings of those names have been erased in the history that Canadians tell each other. Toronto is a case in point.

Most Canadians are quite comfortable with, and even comforted by, the Indigenous origins of the names of the places they call home. But only to a point. The names must remain vague – empty references – rather than carry the burden of Canada’s colonial history and the erasure of Indigenous ownership of lands.

Too many Canadians have a quaint notion that Canada was founded by the English and French, with the contributions of Indigenous Peoples little more than a few names like “Manitoba” and some help in the War of 1812. Regardless, for those with knowledge deeper than a puddle, the renaming of lakes, rivers, and lands by the settler state is widely recognized as a colonialist tool used extensively throughout North, Central, and South America.

As the famed University of California Berkeley geographer Bernard Nietschmann put it, “More Indigenous territory has been claimed by maps than by guns. And more Indigenous territory can be reclaimed and defended by maps than by guns.”

Whether intentional or not, the effect of colonial place names on the Canadian psyche has been to perpetuate the myth that there were vast empty territories, what Europeans called terra nullius, available for the taking. Equally damaging is the belief that Indigenous Peoples were immigrants to North America, like the Europeans after them, and therefore Indigenous ownership over the lands was somehow only temporary until Europeans arrived. These colonial myths remain at the heart of ongoing conflicts over land today.

The educational system has failed Canadians as much as it has failed Indigenous Peoples, for the history Canadians tell each other about Canada is not the history Indigenous people share with each other about this land. Canadian history, as written by Canadians, is so incomplete and devoid of Indigenous history and knowledge that it leads many Indigenous people to believe Canadians are, well, dumb. Not dumb generally, just behind the curve when it comes to Indigenous issues and history and being able to discuss credible paths forward. I recognize, however, this is often through no fault of individuals themselves. How can we expect Canadians to know what they aren’t taught?

Renaming the person

This winter, CBC reported on the story of a girl in Iceland who is listed simply as “girl” on her birth certificate. It seems the name her parents chose does not conform to the 1,800-odd pre-approved legal names for girls in Iceland. An online poll asked Canadians if they agreed with Iceland’s “official name list.” Not surprisingly, about 60 per cent disagreed.

My partner is Anishinaabe. Like so many Indigenous people, his Anishinaabe name is not the name on his birth certificate. He is currently trying to get his name changed to his great-grandfather’s name, which was Waabshkii’ogin (pronounced Waab-shkee-o-gun meaning “white feather”). One name. Not a first and last name. All one name.

Perhaps his great-grandfather did have other names, but the name that stuck as the family name became “White” because, as the story goes, Waabshkii’ogin was the name he had at the time people were registered in Treaty 3 territory. All names were listed in English, and the translator, not fluent in Anishinaabemowin, shortened it to “White” on the official record.

According to Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada (AANDC), “As early as 1850, the colonial government in British North America began to keep and maintain records to identify individual Indians and the bands to which they belonged. These records helped agents of the Crown to determine which people were eligible for treaty and interest benefits under specific treaties.” In 1951, those lists officially became the Indian Register.

Department documents further state: “Under the Indian Act, the Registrar – an employee of AANDC – is the sole authority for determining which names will be added, deleted, or omitted from the Register.” So while registration for “Indians” is done in Ottawa, legal name changes are the jurisdiction of the provinces.

In Ontario, this happens in Thunder Bay. We’ve learned that a legal name in Canada must contain a “first and last name.” Consequently, my partner’s attempt to reclaim a family name like Waabshkii’ogin and return to his community’s traditional forms of naming, with no separate last names, is outlawed in Canada. Suddenly Iceland’s strange naming policies don’t seem so foreign.

How can we as Indigenous Peoples begin to reclaim our own names and discard our colonial past if our names are not even legally possible, if they must conform to Eurocentric norms of naming and identity?

My own attempts at reclaiming are done one name and one word at a time. One by one, I am trying to learn the original names of places around me and speak their names out into words. I am awakening into sounds and songs my respect for the places of my ancestors and the sacred ground I walk on.