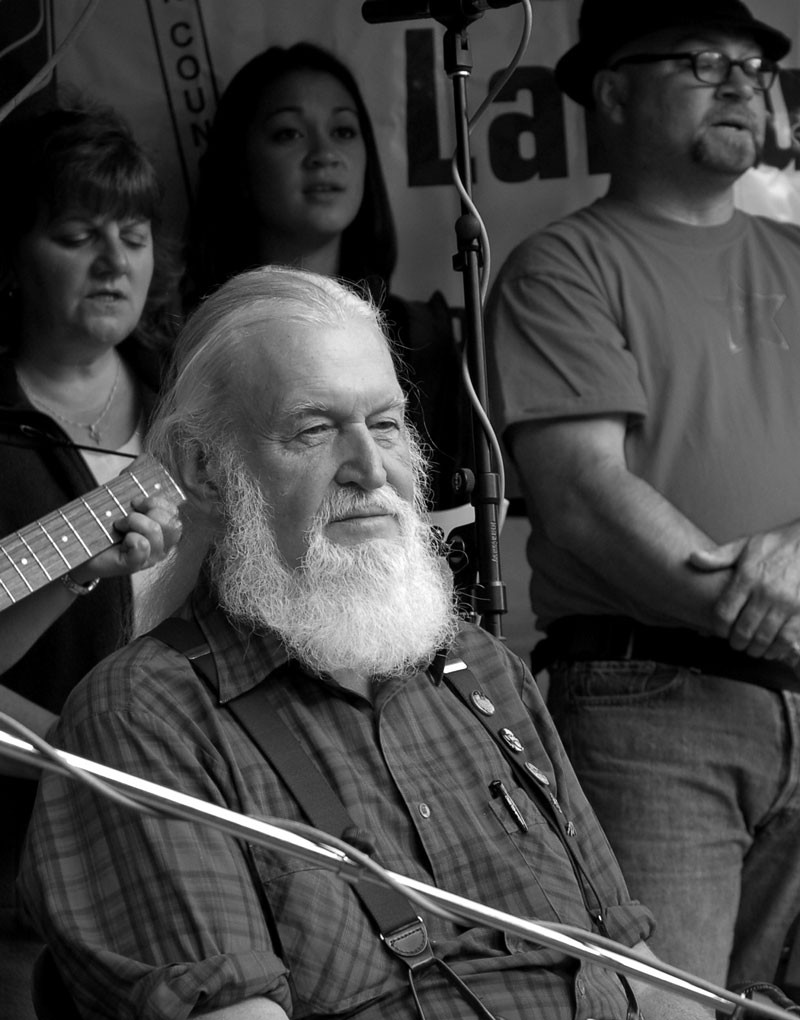

The Golden Voice of the Great Southwest, Utah Phillips is the embodiment of folk music. A Korean War vet fighting for peace as a political activist, Utah was destined to make himself heard. In 1969, blacklisting and poverty pushed him into the folk scene, and its nourishing community kept him there. Utah drew on his own life experience while learning and singing about the life experience of countless others. Having criss-crossed the US as a vagabond, sharing his love of histories both written and oral, Phillips soon found himself with a plethora of stories to tell. Now, close to 40 years later, he is still telling them with as much passion and humour as he ever did.

Clare Powell caught up with Phillips at the Regina Folk Festival in August.

Briarpatch: You’ve been in the entertainment industry for a long, long time. How long?

Utah Phillips: Well, I’m not in the entertainment industry, I’m in the entertainment trade. I work at a sub-industrial level. I make a living and not a killing, see? I avoid capitalism as much as I can. In fact, my record label, which I own, is called On Strike Music: I’m on strike against the music industry.

What were you doing politically before you started travelling and singing?

All during the 60s I was politically active in Utah. In 1968 I was nominated to run for the US Senate on the Peace and Freedom ticket as a peace candidate and as a veteran of the Korean War. But to do that, I had to take a leave of absence from my job as a state archivist. We ran a full campaign all over Utah and got on the ballot. Our presidential candidate was Eldridge Cleaver, the great African American who wrote Soul on Ice.

When the campaign was over, my job had vanished. The archives that I worked for were under the governor’s office, and the governor was a Democrat. We had just prevented the Democratic Party from winning. Every time I tried to get a job anywhere in the state, somebody would call up and say, “Don’t hire this guy.”

So what did you do?

I hung on for a year living on a cot in the back of a warehouse, trying to keep a little draft resistance office open. Finally, friends prevailed upon me. They said, “You’ve run out of moves here. Why don’t you leave Utah and try to make a living telling stories and singing songs?” Which in Utah at that time seemed either criminal or absurd.

But, by god, I left Utah in late 1969. I had three companions: Hal, a good poet and comrade of mine; Larry, an acid-burned out Vietnam vet; and John, manager of the Utah Free Press, the socialist monthly. He was a French communist in exile from France, who had to be delivered to the port of New York for deportation. We had 75 bucks between us, and at midnight, with the cops on our tail, we got in my old VW bus in the rain and drove out of Utah.

So it all started with a police chase. That’s wonderful.

Not long after that, I fell in with the folk music community, this vast music family that had been spawned by the folk revival. They took me in. I knew all these songs and I wrote some too. I’d sing them for anyone. I’d sing them in a living room, in a backyard, on a picket line. It never occurred to me that anyone made a trade out of it.

What was that like?

It was great. We were living cheap and travelling across the belly of the continent in old cars, sleeping on couches and floors, playing for $25 here, $25 there. We learned songs from each other and made up songs when we thought it was necessary. Recording was somewhere on the horizon and having an agent was off the map entirely. And that’s where I began.

Can you describe the folk movement then and now?

It was like a family. Still is a family. Organized folk music is the healthiest and best thing that happened in the United States. Probably Canada too. It’s participatory, it’s creative, it’s inexpensive. People take care of each other’s kids, have potluck suppers. It’s building community; the music, dancing and story telling become an organic part of it. People are liberated to do what they were always intended to do: be part of the glue that holds communities together.

Left-leaning Canadians tend to look down our noses at Americans and their lousy government, but of course, we’ve got one that’s just about as bad, a George Bush clone. Can you talk about some of the grassroots organizing going on in the US now?

Well, I don’t travel as much any more, but I still get out as much as I can. I love travelling. It’s like getting paid to go to school. I go into the streets and ask questions. And I’ll tell you what I see happening.

These people at the top, the Bush Administration and their cronies, are completely alienated from anything real that’s happening down at the bottom. Their eyes are looking some place else. And those of us at the bottom have awakened to the fact that there�s nothing that’s going to come down and rescue us. And it’s not just the counter-cultural people or political people that realize this. In my town, everybody realizes it.

Communities are getting organized. I see it blossoming all over the United States. And I’m here to announce that we are building, from the bottom up, the new within the shell of the old. In a very quiet and very patient and very solid way, we’re networking and pushing up from the bottom.

We’re not going to organize vertically, we’re not going to bring down those big institutions; we’re going to organize horizontally and rise like the tide.

They fight with money, and we resist with time. And they’re going to run out of money before we run out of time.

Clare Powell, now retired, spent 16 years as a Communications Representative with CUPE, and is a former editor of Briarpatch.

To start your subscription immediately, call (306) 525-2949, email us, or subscribe online.