Who is in jail in today’s Haiti, it seems, has a lot more to do with stifling political dissent than with bringing criminals to justice. And Canada has played a key role.

Note: Background information, a glossary of key groups, and resources for further reading can be found at the end of this article.

There were no kids present in the long line of relatives waiting outside the prison gates in Port-au-Prince. Haitian regulations bar children from visiting the National Penitentiary, and it is in fact doubtful whether many would have endured the hot and bothered atmosphere that prevailed that day outside the city lock-up. Under the penetrating stares of Jordanian peacekeepers, 200 Haitian women had assembled in the busy street and were waiting stoically to see their imprisoned loved ones. Filing past a UN armoured vehicle, clutching bundles of food and medicine, they advanced in slow intervals toward a barbed-wire checkpoint.

Once inside, the women and I were frisked and checked for ID before we were let into an enclosed courtyard where a few dozen men, pressed against the separation fence, stuck hands through the bars and struggled to make themselves heard against the background clamour. According to penitentiary procedure, prisoners are entitled to one fifteen minute visit weekly from an adult relative. But what makes detention particularly tedious for so many in the penal system is the fact that the vast majority-89 percent-of Haiti’s detainees have yet to be tried.1

In May of this year, the Brussels-based NGO International Crisis Group (ICG) issued a report damning the state of Haiti’s “overcrowded, understaffed and insecure prisons.” The report underlines persistent problems such as inadequate food supply and a high rate of disease, and notes that with 2,500 inmates, the National Penitentiary is crammed to eight times capacity. The ICG urges donor governments and stakeholders to “establish a prison construction fund” and singles out Canada for qualified praise as the only country to have “pledged to pay for construction, maintenance, and substantial modernisation” of Haiti’s jails.2

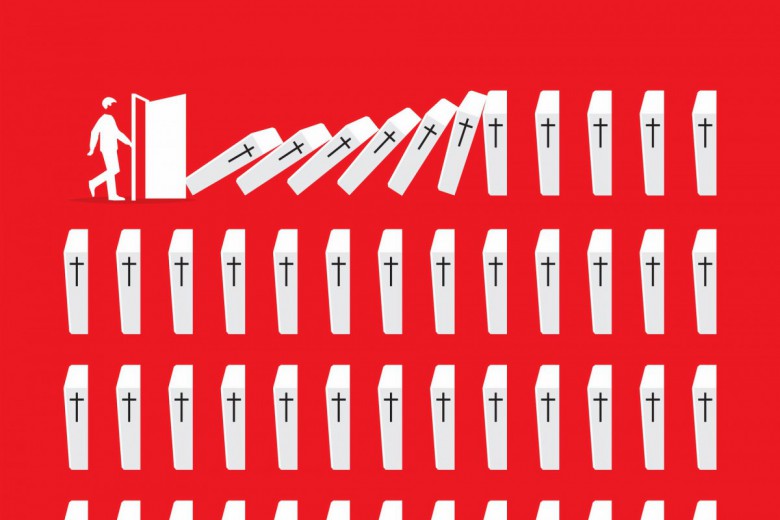

The ICG’s prescription for Haiti places it in the camp of those who see prison reform as a series of managerial correctives that should be applied efficiently. Such an approach, however, fails to raise the significant question of who is in jail in today’s Haiti, and why. According to published figures, the country’s prison population has swollen from around 3,500 in 2003 to 5,500 currently,3 while the rate of pre-trial detention has climbed from 80 percent to 89 percent during the same period.4 And while the ICG assumes that the main function of the judicial system has been “to combat urban gangs and organized crime” many dissidents in Haiti and abroad suspect the state’s motives have much more to do with stifling political dissent among the poorest segments of Haiti’s population.

Members of the left-leaning Fanmi Lavalas party recall that following the foreign-backed February 2004 coup d‘état against their government, large numbers of journalists, elected politicians and community organizers affiliated with Fanmi Lavalas were imprisoned on unsubstantiated charges. Deposed Lavalas Prime Minister Yvon Neptune notes that during his own two-year incarceration, “most of the people who were dragged into the Penitentiary were sympathizers of Fanmi Lavalas, coming from the underprivileged areas of the city. They were arrested, really, in bundles. They would come every day, every day. They were mistreated.”

Fanmi Lavalas was a popular movement that emphasized schools and infrastructure for the rural poor. For party supporters, the coup and its traumatic aftermath are an open wound. Three and a half years after the event, charismatic former president Jean-Bertrand Aristide remains in exile. The pattern of mass arrests-6,000 during March 20045-removed key spokespeople from the political arena and has hampered the movement’s recovery. Canada and the U.S., which provided both diplomatic and logistical backing to the overthrow, then lobbied for the deployment of an 8,000-strong force of UN peacekeepers. The United Nations Stabilization Mission in Haiti-or MINUSTAH, as it has come to be known-operates with official impunity, and has been criticized for its violent incursions into poor neighbourhoods.

In this context, questions persist concerning the ability of the current elected President René Préval to correct cases of political detention that occurred under the coup régime. Until confidence in the justice system is established, critics will continue to ask whether new foreign-built jails will not merely enhance the state’s repressive capacity by allowing it to warehouse larger numbers of political detainees.

My guardian angel during my jail visit and afterwards was Guerline Dauphin, a tall, spunky woman in her mid-thirties who is active with the Association of Family and Friends of Political Prisoners, a group formed in the aftermath of the 2004 coup. Over the course of a few days, Guerline would guide (and sometimes pull) me through the complex of market stalls that line the streets around the jail. My ears strained to decode her rapid-fire Creole as she recited the latest in Port-au-Prince gossip: apparently, UN soldiers had been spotted stealing people’s pigs.

Yet for all her energy, Guerline Dauphin looked tired. The tribulations of the Dauphin family resemble those that have faced many Haitians since 2004. After Aristide’s departure, Guerline, then a courier at the National Palace, was one of several thousand state employees to lose her job. On March 1, 2004, her husband Roland, a Fanmi Lavalas activist, was arrested by paramilitaries from a right-wing rebel force that had entered the capital. Held without charge or warrant for several days, Roland Dauphin was eventually indicted for participation in political violence in the town of Saint-Marc, an accusation he denies. More than three years after his arrest, Roland remains detained at the National Penitentiary, awaiting trial.

I asked Guerline how she coped with the day-to-day stress of conducting prisoner advocacy, collecting and delivering medicine to Roland, who has a prostate condition, and caring for their 12 year-old daughter.

“I’m one strong gal” she said simply.

As a Canadian in Haiti, I was struck by my country’s status as a regional power. On a main street of the capital, the multi-story Canadian embassy caters to the frequent comings and goings of RCMP officers, officials, and NGO staffers. Lacking the global reach of the United States, Canada’s strategy has been to focus funding and diplomacy on select countries such as Mali and Haiti, where the use of French gives Canadians an edge. Québec’s success in modernizing economically and constructing a social democracy during the Quiet Revolution is sometimes cited by Canadian officials as a role model for Third World development.

But Canada’s emotional and ideological attachment to this precedent, bolstered by a paternalistic attitude towards Haitian development, have left Canada’s foreign policy directors hostile toward genuine grassroots development alternatives. Starting in 2000, Ottawa reduced its aid to the Fanmi Lavalas government, whose priority of broad-based empowerment rather than middle-class consolidation of power put it at variance with the made-in-Canada approach. In 2003, the Canadian Francophonie Minister Denis Paradis hosted an international meeting at which the French, American, and Canadian governments resolved to promote régime change in Port-au-Prince.6

Regretably, emerging evidence suggests that Canada used its position as an aid provider to vent its animus against the Fanmi Lavalas party even after that party had been deposed, and to promote policies that have contributed to the prolonged detention of Roland Dauphin and so many others.

Mont Calvary rises above the neighbourhood of La Scierie. (Photo: Wadner Pierre)

Saint-Marc is a small port city located a hundred kilometres north of the capital. In February 2004, it became a scene of violent conflict as an insurgency of former military men poured into northern Haiti from the Dominican Republic. On February 5, the city of Gonaives fell following a fight with rebels. On February 7, the Saint-Marc police station was attacked by local opposition forces, and on the 11th an arson attack against a local health clinic provoked a shoot-out in the neighbourhood of La Scierie between police (bolstered, according to some accounts, by a pro-government volunteer force) and an armed local anti-government group known as Ramicosm. Haitian and international news reports of the time mention four to five deaths in the Saint-Marc clashes of February 11.

Before long, however, a Canadian-linked NGO operating in Port-au-Prince, with no field presence in Saint-Marc, advanced allegations of something more sinister. On March 2, the National Coalition for Haitian Rights (NCHR) issued a press release denouncing what it termed the “massacre” or “genocide” of La Scierie. According to NCHR, “on 11 February 2004, officers from specialized units of the Haitian National Police … and heavily armed civilians … besieged the district of Scierie in Saint-Marc… . The loss of that day … includes more than fifty (50) people dead or reported missing… . Inhumane acts inspired by political motives … [were] carried out as the execution of a plan ordered against a civilian group.”7

As NCHR issued its statement, groups of rebel soldiers had penetrated the capital and were arresting Fanmi Lavalas sympathizers. Canadian, U.S., and Chilean armed forces had dropped into the country uninvited. The names of wanted persons were read on the radio, while in Saint-Marc, lynch mobs hounded government supporters, dragging one woman, Jeanty Renonce, behind a pick-up truck, and killing several others.

The notion that the alleged massacre was the fruit of a “plan” ordered from Port-au-Prince became the justification for arresting key members of the deposed government, including Prime Minister Yvon Neptune, the Minister of Justice, the Interior Minister, and the National Police Chief. Circumstantially, these allegations were based on the fact that Yvon Neptune had visited Saint-Marc two days before the showdown with Ramicosm. There were also records (but not recordings) of subsequent phone communication between Neptune and Saint-Marc officials.

NCHR’s contention is that the government meant to “socially cleanse” or terrify a specific neighbourhood known for its opposition to Fanmi Lavalas, and in which a number of Ramicosm members lived. A court indictment handed down in late 2005 (under the coup régime) is explicit: the assailants in La Scierie aimed to “eliminate from the world map all those who did not share the viewpoints of the existing authority.”8

In a phone interview, I asked NCHR director Pierre Espérance how he was apprised of the killings. Espérance stated that he, like other group members, first heard of the violence on the radio, and decided to dispatch observers. Arriving in Saint-Marc on February 13, two NCHR delegates questioned La Scierie residents, and were shown “five or six corpses” consistent with media reports of the same day.

According to Espérance, the figure of 50 or more dead was derived from these interviews with locals. What is striking is that the 50-plus dead (or missing) were never named. The indictment, while continuing to claim there were a large number of victims, names exactly eight individuals who are said to have died in La Scierie on February 11. Significantly, the eight were all male-a consideration which strengthens (though it does not prove) the hypothesis that the deaths were the result of an armed clash between pro- and anti-government forces. In a Haitian context, combatants are usually men, while one could expect casualties of both sexes if the objective had been to collectively punish or terrorize a particular neighbourhood for its political position. (By way of comparison, after a July 6, 2005, UN incursion into the pro-Lavalas neighbourhood of Cite Soleil, Port-au-Prince, Doctors Without Borders reported that 20 of the 26 people treated for gunshot wounds were women and children.)

Around the time that it was proffering its accusations, NCHR petitioned Canada’s development agency, CIDA, for $100,000 to provide “material and legal assistance” to survivors of the La Scierie “massacre.”9 CIDA and NCHR had no previous financial connection, but the NGO’s middle-class membership and focus on institution building rather than wealth redistribution made it an attractive partner for CIDA. NCHR’s discomfort with the Lavalas movement was evident in its long track record of denouncing crimes attributed to Fanmi Lavalas supporters while ignoring or minimizing incidents in which Fanmi Lavalas members came across as the victim.

Characteristically, in its March 5 funding proposal, NCHR sought to present itself as an honest broker: “Just as NCHR aided and assisted victims of the Lavalas régime, the organization has the obligation to do the same for Lavalas supporters now coming under attack.” Such claims to impartiality were compromised by a choice to limit the dates covered by the victims’ fund to February 9 through 29, 2004. The victims of anti-Lavalas violence, which peaked in the days following Aristide’s removal on February 29, were thus conveniently excluded.

On March 30, with the $100,000 in CIDA money secured, NCHR issued a new press release indicating that a lawyer had been retained to take testimony from La Scierie survivors. Since then, NCHR has largely set the direction for the court proceedings, ensuring that the focus remains squarely on the accusations against Lavalas supporters. The dates retained for investigation under the indictment are those chosen by the NGO in its funding pitch to CIDA-February 9 to 29. NCHR employee Viles Alizar is cited as a witness in the indictment, though he was not in Saint-Marc at the time of the event. Also, an NCHR press release of March 2, 2004, had demanded the arrest of individuals who were subsequently arrested.

Throughout the proceedings, NCHR opposed the pre-trial release of multiple people accused on administrative or compassionate grounds. Since 2004, 28 people, ranging from cabinet ministers to Saint-Marc residents, have been arrested and held for long periods for alleged involvement in La Scierie. Most of those since released have charges pending. Contrary to the Haitian Constitution, which mandates a jury trial for charges involving violent crimes, the indictment indicates that the accused will stand trial before a judge alone.

Of the 28 arrestees, three were still in detention when I visited Haiti this spring. At press time, one, Guerline Dauphin’s husband Roland, remains in jail. One defendant died in January from tuberculosis while in administrative detention, while two of the released defendants have seen the charges against them dropped for technical reasons. No trial date has been set for any of the accused.

The road north from Port-au-Prince hugs the Haitian coastline. Skirting UN outposts, the converted school bus that passes for public transport grinds through stubbly hill country. My decision to scout the scene of the alleged crime was taken almost in secret, because my intention was to conduct random interviews and I did not want Guerline or anyone else offering tips or contacts that might influence my findings.

Boasting portside markets and hand-crafted fishing boats, Saint-Marc is the kind of town you see painted on Haitian canvases that are sold to tourists. Electricity service is sporadic, however, and visitors infrequent. Above the neighbourhood of La Scierie looms Mount Calvary, a sere, thorn-covered slope where, according to the indictment, a government helicopter shot up civilians fleeing the violence in the streets. Three of the corpses referenced in the initial media reports were discovered on Calvary. Fanmi Lavalas supporters contend that armed Ramicosm members fleeing the scene retreated into the La Scierie neighbourhood and up Calvary, where a firefight ensued.10 Anti-Lavalas elements, however, stress the presence of the helicopter, and describe a slaughter of innocents.

Contradictions between the two sides also extend to the number of dead, the question of which side instigated the fighting, and the degree of participation (if any) of a pro-government volunteer force, known as Bale Wouze, in pursuing arson suspects into La Scierie. But in my investigations it seemed useful to focus on the helicopter story because it provides a graphic, easily investigable detail that can act as a litmus test for the credibility of each side’s story.

“I’ll be frank” said Jean, 25, a La Scierie resident. “I’m telling you what I saw. Bullets started flying thick and fast around 11 a.m. Between 11 and 12 the helicopter came … from the direction of Port-au-Prince. When it came it did a circle over Saint-Marc.When it was over Saint-Marc it doubled back. It took a swoop over people’s heads, [flying] really low to check them out. But I didn’t see it shoot.”

According to Jean, in the days before February 11, anti-government Ramicosm members had established a curfew and barricaded the main access road to the neighbourhood. “People felt secure.” But on the morning of the 11th, “at around seven or eight o’clock, the pro-government Bale Wouze were getting the area under their command. They cleared out the barricades and they entered the neighbourhood.” Subsequently, at “around 9:30 or 10 o’clock, passions began to mount so that nobody was able to stay at home. [People] left their houses to go to the mountain.” Jean recalled seeing 15 or 20 people he identified as members of Bale Wouze. Watching from the slope he could see flames in La Scierie. He stated that he was on the mountain along with a large number of residents when the helicopter came.

Jean’s story can be considered alongside that of Elysée, 50, a mason and La Scierie resident, who watched the helicopter from a distance of 500 metres around noon and notes that he did not see it shoot. Elysée says that early that day he saw Ramicosm men running along the road from the direction of the barricade toward the mountain. Bale Wouze members appeared about an hour later, and shots were audible from around 10:30 a.m. After the confrontation, Elysée observed four corpses: two near the top of the mountain, and two further down.

Fétière, 42, a carpenter who identifies himself as a Ramicosm member, recalled seeing “10 or 12 corpses” of whom he named three. Fétière says he saw the helicopter, but did not see it fire.

Out of five interviews I conducted at random in La Scierie, four witnesses claim to have seen the helicopter. Of these four, three, including Jean, who was on the mountain, deny seeing the chopper shoot. The exception, Higgens, 40, a gardener, initially stated that he had left the neighbourhood an hour before the helicopter appeared.

In attempting to reconstruct the events that day, it can be stated with some degree of certainty that following the arson attack by opposition forces against the health clinic (which is known to have occurred just after 7:30 a.m.), Ramicosm members fled toward their home base in La Scierie, taking refuge from their pursuers behind the erected barricades. Police, including special forces who had been sent to Saint-Marc following the recent vandalism of the police station, tried to force passage. In this context, it would be entirely plausible for the situation to have degenerated organically, without any central government planning or high-level involvement. Similarly, it is not in itself incriminating that Fanmi Lavalas officials, facing armed rebellion, would have followed developments in Saint-Marc closely, telephoning their local counterparts during the days prior to (and indeed, on) the 11th.

It is conceivable that specific abuses (for example, house arson) were committed by some volunteers or police officers on the ground. Such questions are important enough to merit impartial inquiry, though this would require the presentation of credible witness accounts and material evidence, in place of the NCHR’s unsubstantiated accusations.

As for the helicopter, it would appear that it was dispatched in some official capacity to observe events in Saint-Marc, but that it either did not open fire, or did not fire regularly or for any length of time.

The hypothesis of, at most, occasional gunfire from the helicopter is clearly more consistent with an attempt to target specific, perceived combatants, rather than a wholesale attempt to mow down the population, or anything resembling a “massacre” or “genocide.”

There is no doubt that the events of La Scierie were traumatic for most of the inhabitants. Residents were aware of the neighbourhood’s reputation as an opposition stronghold, and in the context of a near civil war in a country long marked by political violence under past dictatorships, the worst fears of opponents to the government must have seemed credible. Jean observes that after the shoot-out, “there were a lot [of my relatives] who left their houses, and they returned only after the 29th, after the departure of the President.”

Because my repeated requests for a one-on-one jail visit with Roland Dauphin were denied by prison authorities, I was unable to interview him about his experience on February 11. Following lengthy legal work, a Haitian lawyer obtained the liberation of two of Roland’s co-defendants through a reference to a constitutional provision prohibiting unreasonable pre-trial detention. They became free men the day after I left Haiti.

After four weeks in the country, conducting interviews and collecting documents, I can summarize my findings as follows:

- The denial of a jury trial, which typically requires a higher burden of proof for conviction than a trial by judge, is a violation of the defendants’ constitutional rights;

- The “conspiracy” allegation against politicians who were not physically present in Saint-Marc on February 11, 2004, is based on conjecture;

- The failure of the Saint-Marc court to prosecute, and of NCHR to publicize, cases in which Lavalas sympathizers were killed by lynch mobs in March 2004 shows a partisan bias;

- The 50 victims said to have died in La Scierie have not been named. Moreover, the figure of 50 killed is inconsistent with the five or six corpses that were actually found.

- Prolonged pre-trial detention, which is legally prohibited, may well be a dilatory tactic to prevent known Fanmi Lavalas activists from re-entering the political process.

In this context, Canada’s decision to fund a legal aid project with such a partisan agenda displays either surprising ignorance or active complicity in the very partisan game that NCHR is playing. Given Canada’s unacknowledged role in the overthrow of the Aristide government and its enthusiastic support for the post-coup régime, complicity seems a more likely explanation than ignorance. Further investigation into the mis-allocation of Canadian aid dollars and the degree of Canadian complicity in violating Haiti’s sovereignty and Haitians’ human rights is clearly warranted.

On the day before I left Haiti, I met with former Prime Minister Yvon Neptune, whose ordeal is in many ways emblematic of the La Scierie process. Deposed by the coup government, denounced on the radio, his arrest demanded by NCHR, Neptune turned himself in to authorities in June 2004, expecting to be exonerated in a quick trial. Instead he was jailed in the National Penitentiary for over two years without trial. Following international pressure and a hunger strike which brought him close to death, Neptune was eventually freed in July 2006. Charges were finally dropped during the month I met him, though Neptune may not have known this at the time.

I asked Neptune what he expected from the Haitian judicial system.

“There is no Haitian judicial system” he responded. “There is a club.”

And it is a club in which Canada is unfortunately a paying member.

Chris Scott is a Montréal-based activist who has traveled in the former Soviet Union, Latin America, Senegal, and most recently in Haiti, in March and April of this year.

Notes

1 See “Prison Planet” Foreign Policy, May/June 2007 (p.31).

2 International Crisis Group, Haiti: Prison Reform and the Rule of Law. May 4, 2007.

3 The 2003 figure is derived from a list of prison populations cited in a report by the National Coalition for Haitian Rights titled Prison Conditions in Haiti, released Oct. 30, 2003. The current figure of 5,500 is provided in the May 4 International Crisis Group report.

4 Interview with lawyer Brian Concannon of the Oregon-based Institute for Justice and Democracy in Haiti, May 27, 2007.

5 Interview with lawyer Evel Fanfan of the Association d’Universitaires Motivés pour un Haiti de Droit (AUMOHD), April 24, 2007.

6 See Michel Vastel, “Aristide Doit Partir” L’actualité March 15, 2003.

7 The full press release is available online at http://www.nchrhaiti.org/article.php3?id_article=150. NCHR was originally a New-York based group formed to defend the rights of Haitian immigrants in the United States. The activities described in this article are those of the Port-au-Prince chapter. In April 2005, NCHR Port-au-Prince set up as a separate organization, the Reseau National de Défense des Droits Humains (RNDDH) following a dispute with the parent organization occasioned by the Port-au-Prince chapter’s one-sided declarations during the legal follow-up to events in Saint-Marc/La Scierie.

8 The indictment, or in French, Ordonnance, is the work of a pre-trial “investigating judge” who in the Haitian legal system plays a role analogous to our crown prosecutor. This indictment was titled Massacre de la Scierie (Saint-Marc), and was delivered on September 14, 2005, by Madame Justice Cluny Jules.

9 Correspondence from NCHR released under the Access to Information Act following a request by Anthony Fenton. Date of release: December 16, 2005.

10 For a summary of events on the day of February 11, 2004, from a pro-Lavalas standpoint, consult the booklet A propos du Génocide de la Scierie: Exiger de la NCHR Toute la Verité produced by Ronald Saint-Jean with the Comitée de Défense des Droits du Peuple Haiten, Port-au-Prince, July 2004.

Background

For those seeking some context on recent events in Haiti, MADRE’s brief country overview of Haiti is an excellent place to start.

For an overview of recent Haitian history, and Canada’s prominent role in the destabilization of Haitian democracy, read the excellent account available at www.outofhaiti.ca/

Glossary of groups and organizations mentioned in this article

Bale Wouze: A Saint-Marc-based popular organization with links to Fanmi Lavalas.

Fanmi Lavalas: A leftist political party led by former President Jean Bertrand Aristide.

International Crisis Group (ICG): A Brussels-based non-governmental organization committed to the prevention and resolution of deadly conflict.

MINUSTAH: The United Nations Stabilization Mission in Haiti (Mission des Nations Unies pour la stabilisation en Haiti) is a UN Security Council-mandated peacekeeping force that has been operating in Haiti since the coup of 2004. See http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/MINUSTAH for more information.

National Coalition for Haitian Rights (NCHR): The NCHR was originally a New-York based group formed to defend the rights of Haitian immigrants in the United States. The activities described in this article are those of the Port-au-Prince chapter. In April 2005, NCHR Port-au-Prince set up as a separate organization, the Réseau National de Défense des Droits Humains (RNDDH) following a dispute with the parent organization occasioned by the Port-au-Prince chapter’s one-sided declarations during the legal follow-up to events in Saint-Marc/La Scierie.

Ramicosm (Rassemblement des Militants Constuents de Saint-Marc): An anti-Aristide group based in the Saint-Marc neighbourhood of La Scierie.

Resources for further reading and action:

CanadaHaitiAction.ca

CanadaHaitiAction.ca is a collaborative project of the Canada Haiti Action Network, a grassroots group of solidarity activists from across Canada.

OutOfHaiti.ca

The Canada Haiti Action Network’s introductory overview of the suppression of the Left in Haiti.

Haiti Analysis

Haiti Analysis is a recently launched, editorially independent news site dedicated to the dissemination of news and analysis on Haiti’s struggle for democracy. Haitianalysis aims to provide young Haitian journalists with a direct route to English-speaking audiences, bypassing the need for corporate intermediaries.

ZNet’s Haiti Watch

A wide-ranging database of ZNet’s collected articles detailing the Haitian political situation.

“Aristide in Exile”

By Naomi Klein

The Nation

July 14, 2005